Some of you may be noticing a change in format to these emails you’re subscribed to. That’s because I’m now using substack for all newsletters.

For more about what you can find here, check out the About Page. I’d also appreciate if people responded to this poll before it closes.

I hope you stick with me through this change in scenery.

Anyway:

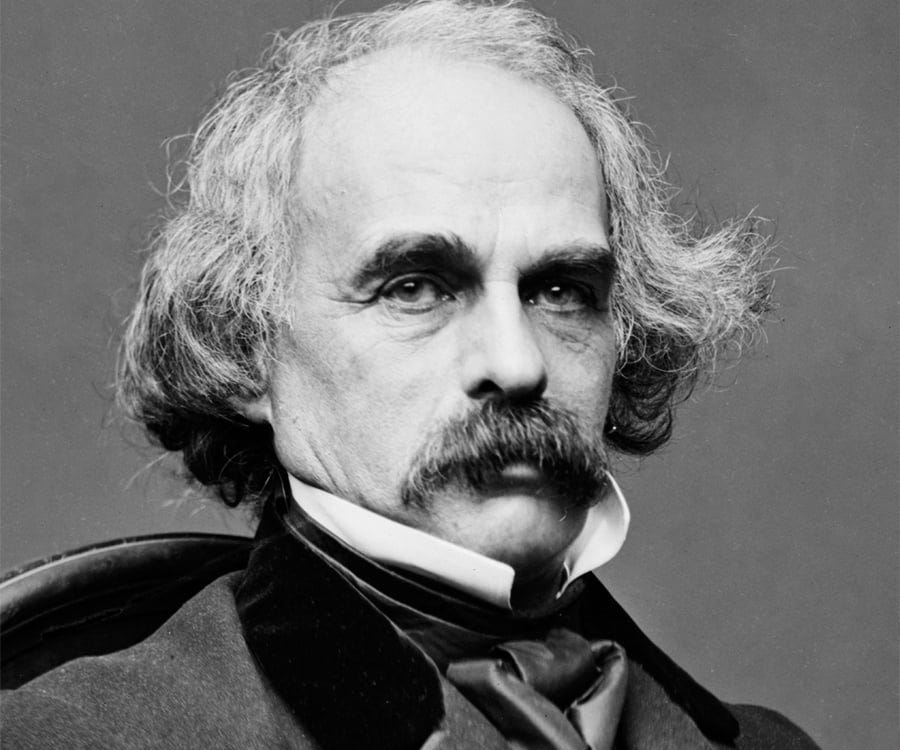

Easy reading is damn hard writing.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne

I read this brief essay by

and I have quibbles, because of course I do. Now, I don’t want this to be read as a repudiation, but rather a response to something that pushed me to consider prose in a way I hadn’t for a long time.I’ve already written about this whole Brandon Sanderson thing, so there’s no point in me retreading old ground, but I think the definitions laid out in Storyletter XPress mostly miss for me, especially the examples lined up: JK Rowling, Dan Brown, Brandon Sanderson, and Suzanne Collins. Though I’ll only stick with Rowling and Brown and Sanderson because I’ve never read Collins.

Brandon Sanderson and the Metrics of Spite

Get Colony Collapse and please review it. I’d appreciate that a lot. I’m still giving away Howl for free right now. I’ll have news about the sequel, Iron Wolf, soon. Also an audiobook for the first two books is coming. For a different perspective on what I’m about to write about, check out J David Osborne’s essay from yesterday. Also, go buy

As those of you here know, I’ve been writing about JK Rowling’s Harry Potter series for a few months and I got to say: that ain’t invisible prose, as laid out in Malone’s essay. It’s not aggressively stylistic, but it is deliberately quirky and amusing. In fact, rather than being invisible, I’d say Rowling’s primary prose goal is amusement. I mean, every character’s name is deliberately distracting on its own. You don’t name a character Peter Pettigrew and Sirius Black and Belatrix Le Strange and Albus Dumbledore unless you’re trying to call attention to something.

But let me post his definition here for those who didn’t click over to read it:

“Invisible prose”, or beige prose, describes a simple, clear, and straightforward style to immerse the reader in the story without drawing attention to the writing itself. Authors who write in this style aim to make the reader forget they’re reading a book.

My main issue here is the assumption that the opposite of invisible prose is driven by an author trying to draw attention to herself.

I’ll quote an essay called The Cardinal Virtue of Prose that Malone quotes at length here to get more into this:

Prose of its very nature is longer than verse, and the virtues peculiar to it manifest themselves gradually. If the cardinal virtue of poetry is love, the cardinal virtue of prose is justice; and, whereas love makes you act and speak on the spur of moment, justice needs inquiry, patience, and a control even of the noblest passions. By justice here I do not mean justice only to particular people or ideas, but a habit of justice in all the processes of thought, a style tranquillized and a form moulded by that habit.

The master of prose is not cold, but will not let any word or image inflame him with a heat irrelevant to his purpose. Unhasting, unresting, he pursues it, subduing all the riches of his mind to it, rejecting all beauties that are not germane to it; making his own beauty out of the very accomplishment of it, out of the whole work and its proportions, so that you must read to the end before you know that it is beautiful.

But he has his reward, for he is trusted and convinces, as those who are at the mercy of their own eloquence do not; and he gives a pleasure all the greater for being hardly noticed. In the best prose, whether narrative or argument, we are so led on as we read, that we do not stop to applaud the writer, nor do we stop to question him.

I think this definition reduces what words are capable of to their purely utilitarian purpose. And I think any reader knows that this isn’t actually what they want.

Lord of the Rings, for example, would be a whole lot shorter if Tolkien cut out all the words to just explain that the Fellowship got from point A to point B. But to pick something more specific, let’s go to the death of Boromir:

Then Boromir had come leaping through the trees. He had made them fight. He slew many of them and the rest fled. But they had not gone far on the way back when they were attacked again, by a hundred Orcs at least, some of them very large, and they shot a rain of arrows: always at Boromir. Boromir had blown his great horn till the woods rang, and at first the Orcs had been dismayed and had drawn back; but when no answer but the echoes came, they had attacked more fiercely than ever. Pippin did not remember much more. His last memory was of Boromir leaning against a tree, plucking out an arrow; then darkness fell suddenly.

Now, if the only purpose of prose is to get the message across, this is terribly overwritten. Instead, Tolkien could have simplified this to:

Boromir attempted to fight off the orcs but there were too many of them. When he called for help, no help came and the orcs overwhelmed him. Pippin did not see him die but knew it was so.

What is lost in the stripping down of language? Would any of you reading this now prefer my version over Tolkien’s?

Perhaps so because there’s no accounting for taste, but I think most would say that we’ve lost more than we’ve gained in rejecting all beauties that are not germane to the scene.

And this passage does not make the reader stop and acknowledge Tolkien. We don’t lose track of the action and think to ourselves There he goes again. Rather, we’re drawn further into the scene. The evocative richness of this passage gives the moment greater weight and makes it come vibrantly alive for us, the reader.

And that, to me, is the entire point of prose. To make words into flesh. To turn stains of ink on a page into emotions wailing in your own chest.

When Boromir plucks an arrow from his chest, it is more than the signal of his death. It is our final image of his bravery, his strength.

And so I reject the idea that prose must be stripped of art and beauty unless it’s specifically demanded by the narrative, because a narrative can never demand such a thing. It’s a looseness to this kind of definition that means the person making such a declaration can exempt whatever they want without argument.

The purpose of prose is not simply to transmit information. We have encyclopedias for that, and, for those wanting to just know the story of Lord of the Rings, the plot is summarized neatly in its wikipedia entry.

No, prose is an art. That Hawthorne quote at the top of this piece is not an argument for prose without artistry or beauty nor is it an argument for simplified prose. Rather, it’s saying that it’s much harder to write in a way that is easy to read.

Hawthorne was not exactly known for artless prose. If you’ve ever struggled with the overwhelming force of Herman Melville’s prose, you have Hawthorne, indirectly, to blame.

It is a curious subject of observation and inquiry, whether hatred and love be not the same thing at bottom. Each, in its utmost development, supposes a high degree of intimacy and heart-knowledge; each renders one individual dependent for the food of his affections and spiritual life upon another; each leaves the passionate lover, or the no less passionate hater, forlorn and desolate by the withdrawal of his object.

—from The Scarlet Letter

There’s nothing confusing here. The prose glides along past you quite easily, but it is not utilitarian or simply written to convey information. And maybe it would be better, for some, if rewritten as: Are hatred and love the same?

I think what Malone and by extension Arthur Clutton-Brock are getting at is something quite different, and it has to do with reader expectation.

As I argued in my piece on Brandon Sanderson, asking if he’s a good or bad writer is missing the point. His audience is not there for the writing, and so even when it’s clunky, it doesn’t slow them down or bother them.

And I would say that Sanderson and Dan Brown (I mention them because Malone does) are not invisible writers, but plain writers who are often clunky.

The monsters almost seemed to blend and shift together, one enormous dark force of howling, miasmic hatred as thick as the air—which seemed to hold in the heat and the humidity, like a merchant hoarding fine rugs.

—from A Memory of Light by Brandon Sanderson

Now, is this invisible? I’d say that this draws far more attention to itself than the death of Boromir above, simply because it’s somewhat confused (why would a merchant hoard rather than sell her wares?) and requires the reader to pause to make sense of what’s really being conveyed here.

On the otherhand, the reader may just blow right past it because they’re not here for the prose. They’re here for the adventure, the characters, and so on.

Which is fine.

A voice spoke, chillingly close. "Do not move." On his hands and knees, the curator froze, turning his head slowly. Only fifteen feet away, outside the sealed gate, the mountainous silhouette of his attacker stared through the iron bars. He was broad and tall, with ghost-pale skin and thinning white hair. His irises were pink with dark red pupils.

—from The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown

Again, this isn’t really invisible, though it is kind of confusing. If this person is in silhouette, how does the curator see the color of his hair, his skin, his eyes?

So I wouldn’t call this invisible. I’d call it clumsy or slightly confused.

Now, that’s not to say we should all Gene Wolfe our prose (though I’d argue it’s not that his prose is generally difficult to follow, but rather the overwhelming nature of all those sentences raining down upon you), but we also shouldn’t lead ourselves to believe that prose doesn’t matter or that plain and unadorned prose is best.

I felt that pressure of time that is perhaps the surest indication we have left childhood behind.

—from The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe

Wolfe is famous for his difficulty, but I’d describe the above as a perfectly good example of easy-reading prose. There’s nothing confusing there or anything to draw the reader out of the story, but it’s also not stripped bare of art and beauty. It’s incredibly evocative for all its brevity, and it has a certain rhythm to it that sticks in your head. Which is not the same thing as distracting prose.

Now, I do have a theory that your writing should be simpler and more straightforward as your story becomes conceptually trickier—and this is something Wolfe often chose not to do. For example, if you’re writing a surreal scene where reality itself begins to bend and blur and finally break, the best way to accomplish this, I think, is by writing as plainly as possible, even to the point of potentially stripping extraneous beauty or metaphors from the prose.

I would say the same is also often true when writing an action scene. If it’s important that the reader follow the action very closely, it’s best to write quite plainly (I’d argue that Sanderson’s writing in this regard often reads like a description of rock, paper, scissors, however).

And this is, I think, where Sanderson’s very straightforward and plain style is useful. His novels are often very rule based and the conclusion often relies on the reader fully understanding the rules of the world.

Sanderson is one of the most famous authors in the world and I would say that he has trained a generation of young readers to expect exactly what they get from his books. They’re not expecting or even wanting language that delights and surprises. They’re showing up for the rules and the action and the characters.

But I think it would be a disservice to readers and writers to lead them to believe that Ursula K Le Guin was writing to draw attention to herself, as the author, or that Octavia Butler just wanted you to applaud her prose.

That they wrote beautifully does not mean they were trying to distract you or were full of ego. Often, the best way to the heart of the matter is through metaphor, through beauty. A transmutation of words into flesh and blood and bone, into thrumming hearts, gasping lungs, and tearful eyes.

We can write that a knife cut or we can write that the blade sliced and we can say that one is better than the other, but I’d argue that we’re just playacting authority (for the record, the blade sliced sounds richer because of consonance, and that makes it feel more evocative, as does the use of blade—somewhat uncommon usage—over the ordinary knife).

Now, for those wondering, the reason I’ve mostly only mentioned genre fiction writers here is because Malone implies that this is an argument between the literary genre and the rest. But Le Guin and Butler and Wolfe and Tolkien wrote powerful and beautiful prose throughout their novels and no one would ever confuse them for literary writers.

I wouldn’t describe any of them as invisible writers, but I find this recent inclination in online SFF writers to equate good prose with snobbery to be shortsighted and limiting. It’s also quite new, this push for plain, utilitarian prose. If anything defined pre-Tolkien fantasy literature, it was the lush evocative prose, and that continued through the 70s with writers like Le Guin or M John Harrison writing powerful and striking prose and possibly culminated in Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun, which Le Guin compared to Melville’s Moby Dick.

Malone states quite plainly that he’s not arguing for one being better than the other (though I think, structurally, this is implicitly coming down in favor of one side), and he’s absolutely correct here. But I think what sometimes passes for invisible prose is actually quite clunky. Worse, when we say that any adornment to prose is simply the egotistical writer calling attention to herself, we tell readers and young writers that prose has no room for artistry, that the only difference between a delectable, perfectly constructed sentence and ad-copy is the writer’s pride. By doing this, we reduce what literature can be.

And I write this whole essay because I care a lot about Science Fiction and Fantasy. I want the writing to be great and I want the books to be fun and exciting and I want to be moved and I want to weep and I want to laugh, and the way we get there is often by hitting several registers within the same piece.

What that means is that styles are tools. As Malone said, one isn’t better than the other (though, again, I think his essay is an argument for one being superior to all others). Rather, each kind of style can be implemented judiciously to improve the work as a whole.

The Lord of the Rings is a good example of this, by the way. It’s often very silly and funny, but also epic, but also mundane, but also beautiful and mythic and rich.

A novel can be all of the above, and I think the best novels are.

If you write solely in one style, regardless of scene or emotional weight to a moment, you risk monotony.

And that’s worse, I think, than occasionally finding a reader who thinks your prose is a bit purply for their liking.

And if you’re one of those kind souls looking to get into my fiction, here are the novels I’ve released recently:

Glossolalia - A Le Guinian fantasy novel about an anarchic community dealing with a disaster

Sing, Behemoth, Sing - Deadwood meets Neon Genesis Evangelion

Howl - Vampire Hunter D meets The Book of the New Sun in this lofi cyberpunk/solarpunk monster hunting adventure

Colony Collapse - Star Trek meets Firefly in the opening episode of this space opera

The Blood Dancers - The standalone sequel to Colony Collapse. Coming 6/21/2023

Iron Wolf - Sequel to Howl. Coming 7/25/2023

Some free books for your trouble:

Hey there, thanks for writing this detailed, thoughtful, and well-crafted response to my article about the perks of invisible prose. After posting mine last week, the various comments helped me understand the subject more broadly.

It’s a subjective topic; however, I realize now that I was injecting my preferences into the article, which came across as dismissive of other writing styles. As I stated, I wholly support other writers embracing their unique styles; the crux of it for me was defending a style that I like to read, therefore, gravitate to when I write. I’ve since revised certain sections to remove these pejoratives, such as “purple prose” and my italicized inflections, but I still need to clarify my overall meaning to convey the point I had in mind, which I think you explained pretty well here:

“Now, I do have a theory that your writing should be simpler and more straightforward as your story becomes conceptually trickier—and this is something Wolfe often chose not to do. For example, if you’re writing a surreal scene where reality itself begins to bend and blur and finally break, the best way to accomplish this, I think, is by writing as plainly as possible, even to the point of potentially stripping extraneous beauty or metaphors from the prose.

I would say the same is also often true when writing an action scene. If it’s important that the reader follow the action very closely, it’s best to write quite plainly (I’d argue that Sanderson’s writing in this regard often reads like a description of rock, paper, scissors, however).”

I enjoy writing action scenes, so that’s likely why I lean into simple prose, that and I’m a developing writer trying to understand the craft. Your article is incredibly insightful, and I aim to share this with my subscribers to invite further discussion. Thank you!

That “Cardinal Virtue of Prose” passage made me wrinkle my nose! Poetry, if anything, feels *less* spur-of-the-moment than prose to me.

I think I would like better to read “beauties not germane” not as a universal call for simplicity, but as a call for precision of beauty - for the opposite of Sanderson’s merchant-hoarding-rugs metaphor. The right thing to do is not to cut out the metaphor and leave the action, but to find a metaphor that clarifies, or surprises, or delights, instead of confuses. That would be beauty germane to the prose. I’d say the beauties in Tolkien’s description of Boromir’s fight are all germane, too. A really good writer knows exactly what to keep and what to discard for maximum effect. But the keeping is as important as the discarding.