Catch up here:

This third novel is the first one that I remember. I mean, there were bits and pieces and certain scenes I remembered from the first two books—though probably what I really remembered was the movie version of the scene—but this is the one where I have a clear picture of the novel in my head.

I would say that this novel is the one that made Harry Potter into Harry Potter. Without this turn in the series, from amusing and enjoyable novels tinged with darkness about kids learning magic at a silly and strange and sometimes frightening school into one that’s growing up with its audience and even shedding the importance of the school itself in doing so, Harry Potter would have remained a series for young children.

And there’s nothing wrong with that, mind, but this novel is growing up with its audience. Harry isn’t ten anymore and neither are his readers.

It’s a very interesting decision, one probably made unconsciously or at least without great deliberation. But the whole series could have remained geared towards 10 year olds. There’s another universe just beyond your fingertips where the entire Harry Potter series remains a children’s series. People would encounter Harry Potter when they’re 8-10 years old and then grow out of them by the time they’re 11-14 while they move onto books with more adult themes.

But instead, Rowling allowed her series to age up with her readers.

I really cannot oversell how important I believe this is to the series’ success. Without this growing up aspect of the series, people wouldn’t have spent a decade reading them and finding them relatable again at each new release. When Harry turned sixteen, so did his readers. When he was graduating Hogwarts, so too were we graduating high school1.

You spend your entire childhood and adolescence jumping back into a series that continually reflects where you’re at in life when each new book is released.

I am the Harry Potter generation, whether I like it or not. If you’re within a few years of me, you are too. Because of this, I’ve been surrounded and forced to reckon with Harry Potter for most of my life. Even me ignoring and not reading Harry Potter functioned, for some, as a specific kind of declaration that bordered on political.

For some people, it was flabbergasting that I wasn’t interested in Harry Potter. These same people are probably shocked that I haven’t seen Avengers 3 or the final Star Wars movie or Avatar 2. And, I mean, I could see all these things, but I just kind of don’t care. Which is pretty normal, honestly.

We don’t all need to like the same things. And if you’re a reader here, it probably won’t surprise you that someone who reviews old games and movies and books also isn’t up to date with popular culture or even niche cultures.

I just…I like what I like and I like it a lot.

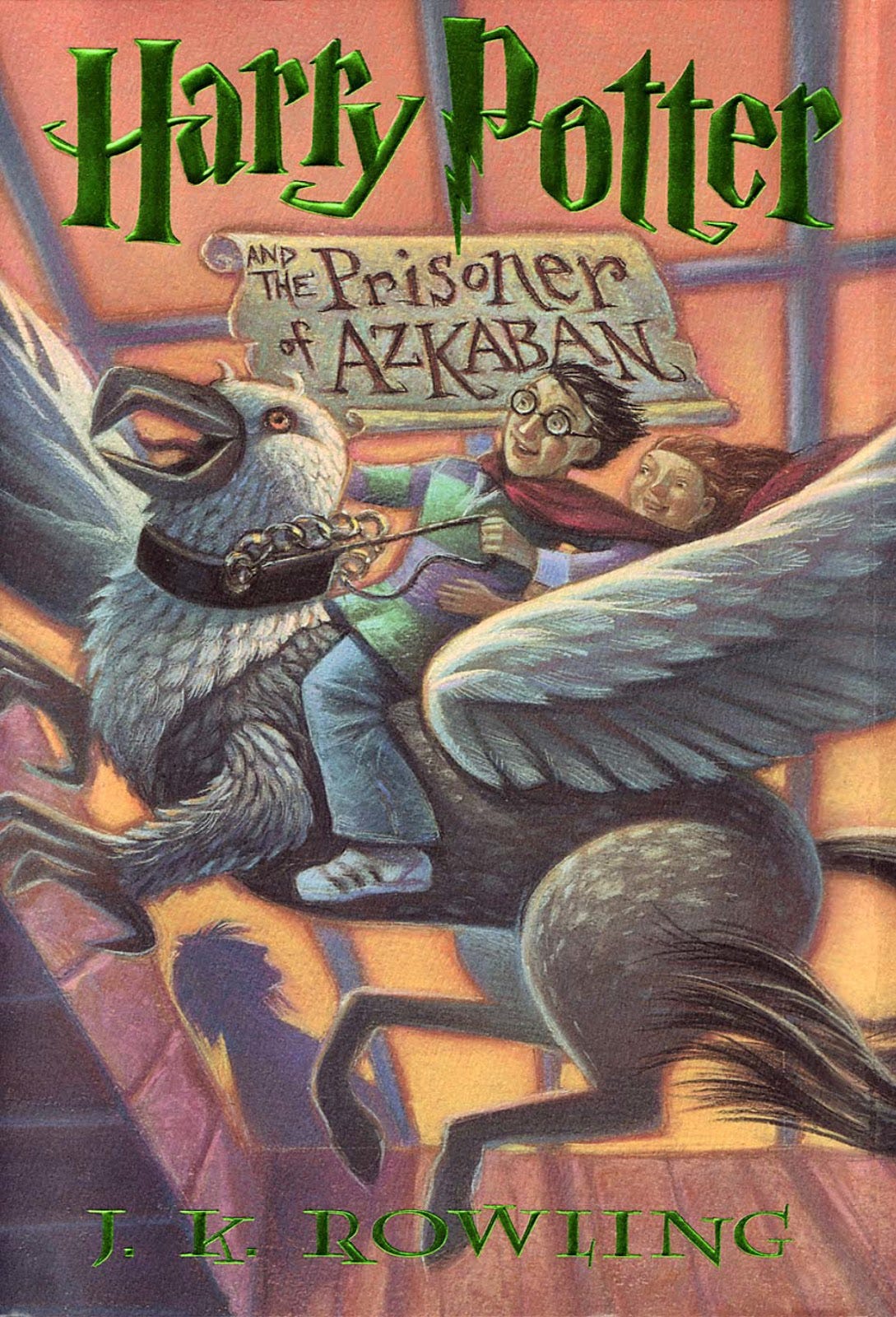

But The Prisoner of Azkaban is, I think, one of the most important books of the past 25 years. Not because it’s one of the best books, but because I believe it’s an inflection point that created the YA genre essentially overnight. And while I’ve probably only read several YA novels in my life, there’s no denying the cultural force that YA literature has become.

I mean, when I met my wife, she was reading the third Hunger Games book and the first movie we saw together was The Hunger Games.

Even when I don’t intend to interact with certain media properties, they inject themselves into my life.

While I’ve been fairly indifferent to the first two Harry Potter books on this reread with most of my interest being caught up in the fact that these became so popular, The Prison of Azkaban is a genuinely good book.

It suffers from many of the same faults of previous novels, but it’s clear that this is the one where Rowling began to mature as a writer. It’s also where she really becomes more of a mystery writer than anything else.

Her first two novels have mysteries at their core, but the foreshadowing is light and the main thrust of the novels are the good times and vibes and the amusing nature of the wizarding world.

Here, it’s all a bit darker. A bit murkier. Rowling spends quite a bit more time setting up the novel and we get the sense that she’s in no rush to bring us to Hogwarts. And even when we get to Hogwarts and the amusing classes and personalities, much more of the focus is on Sirius Black and the various mysteries surrounding him.

Who is he? What does he want with Harry? Why won’t anyone tell Harry why he would want Harry?

I mean, the dang leader of the wizarding world is involved! He meets Harry personally and sets him up to be as safe as possible from this mad murderer.

It’s also the first novel where the professors really become filled out and have relationships and dynamics and grudges of their own. Snape hates Harry Potter for very petty reasons that I have a very Big Problem with (we’ll get to this in a later book) but the various professors and head of houses are primarily amusing blocks who serve very specific functions.

Then we meet Remus Lupin. Perhaps, at this point in the series, the most well rounded and realistic character. He is overfull with humanity, especially in contrast to the rest of the cast, which is interesting since he’s a werewolf.

Like the previous novel, we get some discussion of prejudice and so on when we learn of his lycanthropy. Much like the previous novel, I think it handles this in a very clumsy way, but I think its analogue is basically the addict or the theoretical criminal who can’t help but commit crimes because of desperation and privation.

Lupin can’t hold down a job. People don’t trust him. He’s disheveled and sloppy and opaque with regard to his own past or even with his reasons for disappearing for days at a time.

He’s every struggling addict I’ve ever known.

But he’s also just so alive. He is the first character who seems to exist in the Harry Potter world even when he’s not interacting directly with Harry or doing something that Harry observes.

He has his own relationships and emotions that have nothing to do with the children he teaches.

And, uh, well, I just love werewolves.

I love them a whole lot. And my love for them is different than my love for vampires because, in many ways, I’ve never fully been satisfied with their depiction.

Also, while vampires are powerful and cunning and sexy and romantic, werewolves are, primarily, monsters. They terrify not only others but also themselves. Their monstrousness breaks them in half, especially since there is no reckoning or reconciling the fact that you become an uncontrollable monster every 28 days.

Too, while vampires are made deliberately, werewolves feel much more like a randomly occurring curse. When a werewolf burst out of the night to maul you, the only thing you did wrong was be in its way. The werewolf itself is not thinking.

It’s a wild beast.

A vampire, on the other hand, is making deliberate choices. The vampire may be like Louis from Interview with a Vampire or Lestat, they may be Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula or they may be The Lost Boys.

There’s a certain romantic beauty to vampires. This can be turned tragic or erotic or bestial and monstrous, but the werewolf is always a tragedy.

And we feel that tragedy in Lupin. It’s why we feel so much when he reveals the truth of who he is and who Sirius was so late in the novel.

It’s why it hurts so much when he leaves Hogwarts.

Along with that, we see Harry dealing with the emotions of what this whole series hinges on. His parents were betrayed and murdered. He’s now a wizard who has, through luck and guile and determination, bested Voldemort thrice.

What will he do to the murderer who betrayed his parents?

Despite the violence and rage coursing through him, he finds himself unable to kill Sirius Black, which, you know, is a good thing since Sirius is revealed to have been betrayed himself and innocent of all that he’s been accused of.

But these are real and serious emotions. More than that, the novel ends without some clean resolution. Sirius Black, though proven innocent to Harry, has not been proven innocent to anyone else. Peter Pettigrew, the true betrayer of the Potters, has escaped. Harry has to go back to the Dursleys rather than with his wizarding godfather, Sirius.

A clean resolution isn’t exactly something new for Harry Potter at this point, but usually the major victories far outweigh the rest. Voldemort is stifled and must try again in some new way. Gryffindor may not win the Quidditch Cup, but they win everything else.

Here, Gryffindor wins it all but those who mean harm to Harry are still free and working to resurrect Voldemort’s power. Lupin and Sirius return to being outcasts.

I mean, in some ways this novel is driving home how trivial the events of the school are. Hogwarts continues ever onward but the fate of the world depends on Voldemort remaining powerless. It relies on good people, like Sirius and Lupin, working with the rest of the good wizards to make a better world, to protect it from the dark wizards like Voldemort and his ilk.

And it’s this darkness that pulled the aging children of the Harry Potter fandom fully in. While the darkness has always been there burbling at the edges, this novel launches fully into the life and death nature of this world.

You fell in love with Harry in elementary school for the amusing whimsy. You stayed in love as you tiptoed towards high school because of Remus Lupin and Sirius Black and the terror of Voldemort’s return.

I mean, with just one of his magical artefacts, he was able to kill numerous people the year before. What would his embodied power mean to muggle born wizards and muggles more broadly?

If you were a Harry Potter fan (which I wasn’t), I wonder how you felt at the end of this novel, knowing you’d be waiting at least a year for the next step.

Oh, and before we end this, can I just mention how hilariously absurd quidditch is? Maybe I wasn’t paying enough attention in the previous books or maybe it wasn’t entirely clear, but it struck me in this book that they only play FOUR GAMES THE WHOLE YEAR. Like, what kind of a nonsense season is that!

Imagine if each of the 30 baseball teams in the MLB only played 15 games before the playoffs? I suppose this is how football works, with each team only playing each time in its division once, but it seems way funnier with a league of four to only play each team once.

But I do think this is still one of the funnier understated jokes of Rowling. This absurd game is so silly and stupid, and yet aren’t all sports the same way? Arbitrary rules that only make sense to those who have been following those rules since childhood.

While The Prisoner of Azkaban is the darkest of these first three Harry Potter books, it is also full of amusing little bits of character and wizarding world nonsense. Like Ron not knowing how to use the phone or Hermoine taking classes to study muggles even though she lives in muggle culture with a muggle family.

It’s actually quite a clever balancing act, to keep everything silly and lighthearted while also pulling back the rug to reveal the darkness underneath that threatens to swallow all this delightfully whimsical world.

Does Harry graduate? I honestly can’t remember but I guess I’ll find out soon enough.

Prisoner of Azkaban is my favorite Harry Potter movie because, among other things, they do a great job with the cinematography during the time travel sequence, cueing it up from Harry's perspective where random odd happening and coincidences keep saving him, but he doesn't realize until the end that Future Harry is the one causing them. And as you say, that foreshadowing is a theme of the whole book - it feels like this is the first book in the series where Rowling consciously went back through and inserted the hints and clues in her first draft as purposeful edits rather than just following a fanciful story wherever it took her. Hints about Scabbers missing a finger and interacting with Hermione's cat, hints about Lupin's lycanthropy, hints about the Time Turner, hints about Sirius, Trelawney's seemingly absurd predictions that can be interpreted as correct...the novel is sprinkled with foreshadowing throughout, and it's done artfully enough that they often feel like "Wizards are crazy" window dressing rather than obviously lampshaded clues.

I love this novel too, and you are right that this is the point that Harry and the series as a whole begin to grow up. Another important complexity of the adult world the kids learn in this book is that the justice system can be decidedly unjust. So many popular crime books, movies, podcasts, and TV series make the unstated assumption that what the police and the courts decide is just, and I like that Rowling’s kids’ book has a clearer view of the failures of justice than these works, ostensibly for adults, have.