Cormac and James and a boy

or, the limits of self-examination; or, a tale of myself

I’m e rathke, the author of a number of books. Many of you are here because of Howl so today’s post is perfect for you. Learn more about what you signed up for here. Go here to manage your email notifications.

Writing about writing is a somewhat dangerous pasttime, especially when you’re writing about your own writing. Imagine a hall of mirrors and all of them reflecting the inside of your eye. Not the black hole of your pupil but the viscous gel filled with light.

As some of you know, this year I’ve re/read all of Cormac McCarthy’s novels but I also reread all of James Joyce’s novels (I have not read Finnegans Wake, though I might give it the old plumber’s try) and I find that I must talk about the words that made me who I am, even before I read them.

For I had been circling these writers for years before I finally read either of them.

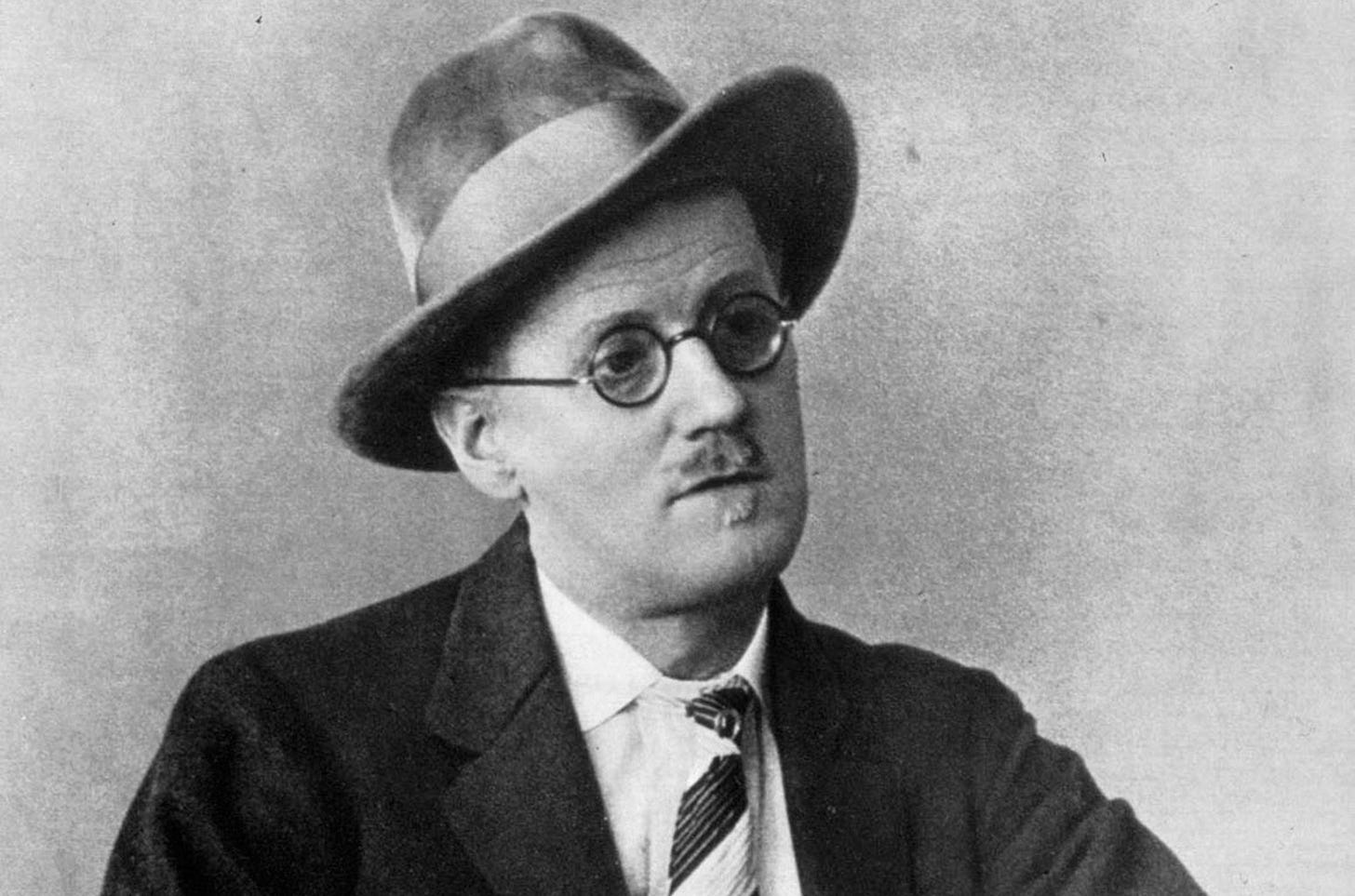

But let’s begin with Joyce.

The reputation of Joyce is big as the Alps and to consider writing a book at all means you must contend, in some way, with him.

One tactic is to simply ignore him. Never bother with him. Don’t even pick up one of his books at the library or bookstore. Just amble on by.

The other is to read him and either allow him to change your life or to build a wall thick enough to keep his diseased language from escaping, from infecting you, from rewriting you, to shut down the mRNA before it slips into your cellstream.

I have long had a strong affinity for Ireland, owing to heritage and familial stories, and you can’t really just browse around about Ireland without running into James Joyce eventually.

And I had been dreaming of one day going to Ireland, to one day walking those Dublin streets that I had yet to even read about. Dublin and Ireland became for me a sort of mecca, a promised land of art and artistry, of the greatest and the oppressed, a seat of revolution.

He wanted to cry quietly but not for himself: for the words, so beautiful and sad, like music.

I’ve been reading about writers for decades and so I knew about Joyce before I ever picked up one of his books. And it was in learning about Joyce that he first took root in me. It also, ultimately, led to some amount of disappointment, but that’s an essay for another day (coming soon!).

But his insistence on language struck me, even before I read a single sentence that he wrote. Perhaps most importantly, though, was the way he took literature by the throat and dragged it away from aristocrats, from Very Important People, and handed it, instead, to all of us.

To me.

To you.

James Joyce birthed the modern world. He certainly birthed the modern conception of art, even if you may rise up and disagree, point to other sources. It was James Joyce who gave us Tolkien, who gave us videogames, who gave us millions of terrible imitators, but also set off quite a few who took him up on his linguistic assault, and even one or two who managed to innovate from him1. Interestingly, one of them was also Irish.

But discovering how Joyce brought literature down to us sweaty, dirty people gave me the first inclination that I actually might be able to do this. Kings and queens and Very Important People have never suited me well2. For those who have read my novels, this is likely no surprise.

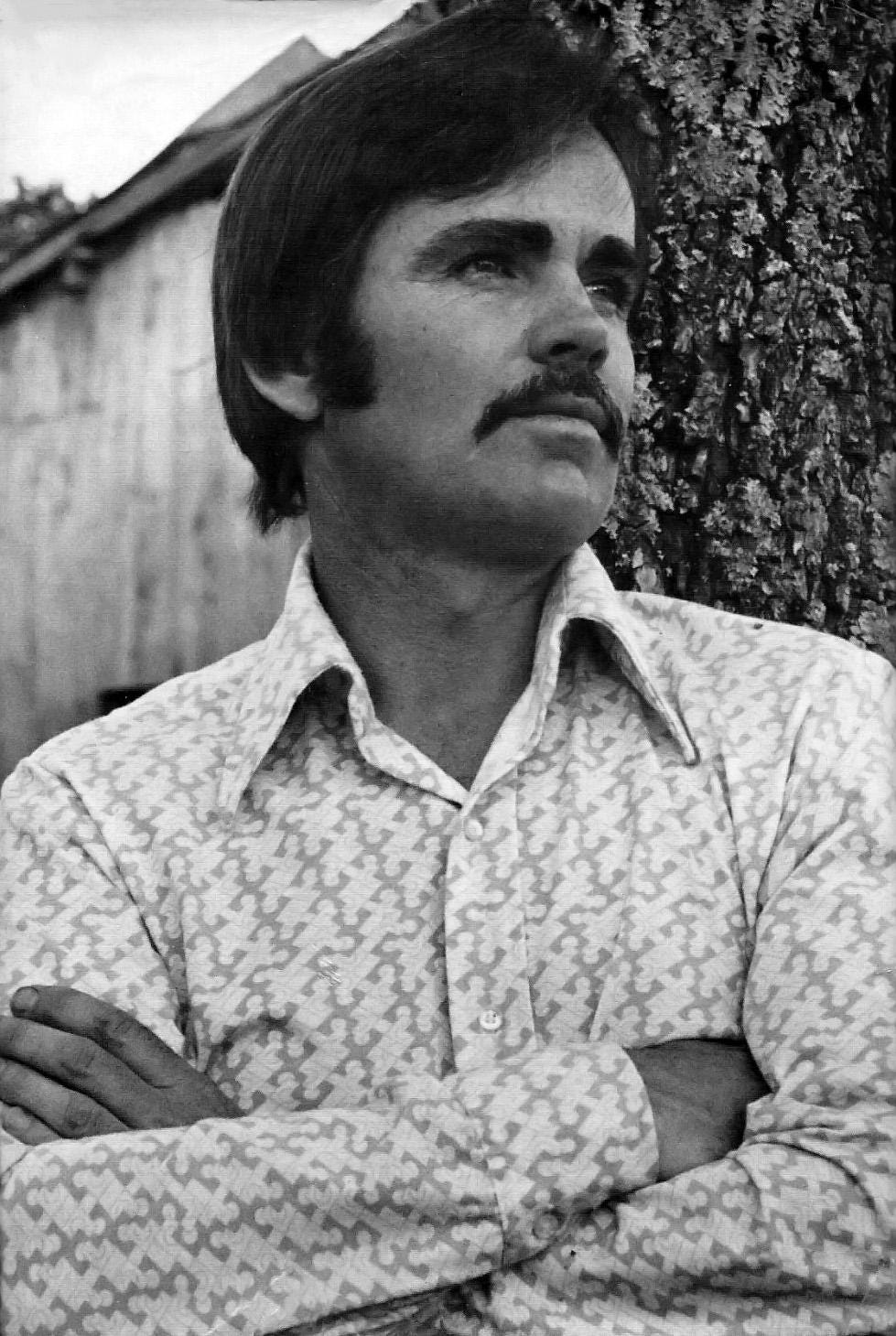

While Joyce had orbited my life for many years, McCarthy arose somewhat suddenly in the wake of The Road. It would take me a few years to finally pick it up and then, of course, there was the Oscar winning No Country for Old Men, which left my jaw on the floor while I stared at Tommy Lee Jones’ ancient face.

I knew about his lack of punctuation, the way he very much did not use quotation marks or even necessarily apostrophes where you’d expect. But by then I was already writing my own stories, not using quotation marks because I agreed with Joyce that they mostly just muddied up a page.

My love of long, complex sentences was set off by neither of these writers, because I hadn’t read them yet, but I had been experimenting with extending the sentence as long as I could, sometimes with a whole mess of commas and so on, but sometimes without anything, writing sentences that stretched for pages and sometimes leaving them fragmented, unresolved.

But I’m also a creature who loves contrast and so I thought it was funny to bookend these absurdly long sentences with very short ones, or very short fragments instead3.

And so imagine my surprise when I read A Portrait of the Artist a year before moving to Ireland and then Ulysses a month before shipping myself there. Two books full of measuring breath. The expansive way he’d stretch sentences and then the short gasp of a three-word sentence fragment.

That Christmas when I was briefly back from Ireland, I swallowed The Road and found the same kind of strange exhilaration.

I’d been reading about these two, studying all that had been said about them, and then I discovered that I had landed upon the same path they’d been traveling for so long.

Imagine going to distant shores. Sailing across the entirety of the world you’ve known. And rather than find a world wholly unknown, you discover a place like home4.

But they also gave me the confidence of my artistic convictions.

It was 2008. I was only 21. I had written hundreds of short stories but no novels, though I was, then, trying to write my first one (didn’t go well!)

But in finding them and finding myself at home inside their words, I was able to grow alongside them, develop with their novels entwined with my own artistic development.

Interestingly, at least to me, I have always found it funny how people seem to only pay attention to Joyce’s linguistic innovations. These have always been the least interesting aspects of his writing to me, though they’re certainly the most noticeable. But, to me, the true revolution of Joyce is a matter of perspective.

Writing about the nobodies of the world, going nowhere, achieving nothing, but turning this into something magisterial. Blowing up our conception of art’s purpose, of her perspective. More than that, we find the most human characters in literature.

Even still, few have so fully made a character. It’s not simply that Leopold Bloom is all of us or any of us but that he is so much himself. Same for Stephen Dedalus. They are not Everyman stand-ins.

They are singular.

And then there’s Molly Bloom who shattered everyone’s world by being so very much herself, so very much unlike anyone who’d ever graced a page previously.

McCarthy has, over the course of his twelve novels, achieved much the same thing. People always comment on the darkness, the style, but so few comment on the humanness of his creations.

Yes, there’s Judge Holden and Anton Chigurh, but there’s also the Man and the Boy and Gene Harrogate and Rinthy Holme and Cornelius Suttree, of course.

I wonder, now, having read Suttree so many years after Joyce, what it would have done to Ulysses for me to have read Suttree first. For Suttree belongs to Joyce in so many ways, but McCarthy pulled his own Bloom out of the city, threw him into the backwoods of Appalachian Tennessee, and set him on his own odyssey of vagrants and grotesqueries.

And I think of a novel I wrote that owes so much to both of these writers, though I thought of neither of them at the time. But I built a cycle, a circle, and I filled it with myself, with all that I knew, and set it in Minneapolis, in my own house, the one I lived at for all these years, and I built it like a swamp that collapses inward like a waterfall and it’s something I still don’t know how to share, who to share it with, or what to do with this strange beast.

But spending the year with McCarthy, with Joyce, I see how the book was birthed from the versions of them I invented in my own head.

My novels:

Glossolalia - A Le Guinian fantasy novel about an anarchic community dealing with a disaster

Sing, Behemoth, Sing - Deadwood meets Neon Genesis Evangelion

Howl - Vampire Hunter D meets The Book of the New Sun in this lofi cyberpunk/solarpunk monster hunting adventure

Colony Collapse - Star Trek meets Firefly in the opening episode of this space opera

The Blood Dancers - The standalone sequel to Colony Collapse.

Iron Wolf - Sequel to Howl. Out now!

Some free books for your trouble:

I have read a lot of experimental fiction that plays around and mucks with language and I think most of the university types need to admit that all their innovating is just a poor rendition of things that Joyce did over a century ago.

I mean, when I read A Song of Ice and Fire by George Martin, I immediately thought of writing a similar series but from the perspective of a farmer or someone who has no power to shape the realms imperiled. As in, someone who must live through a war that they had no part in that’s raging all around them.

Anyone who’s read one of my novels has definitely noticed how often I use terse sentence fragments.

Settlers in the US often commented on how they arrived at a place that seemed idyllic for settling and couldn’t believe the native people of the continent had made no use of such a place. The terrain and layout seemingly designed by God himself for human habitation. The truth, of course, is a whole lot grimmer: native peoples were making use of that land until disease left it empty, possibly even just a few years before Europeans wandered blindly into it.

Just such a wonderful piece. Loved it, loved it, loved it. Keep kicking ass! You’re on the right track!

If you go for FW, I recommend the Joseph Campbell guidebook …