a hole in the floor

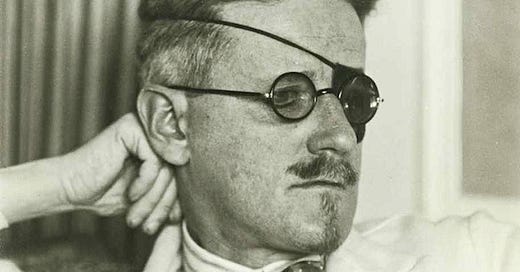

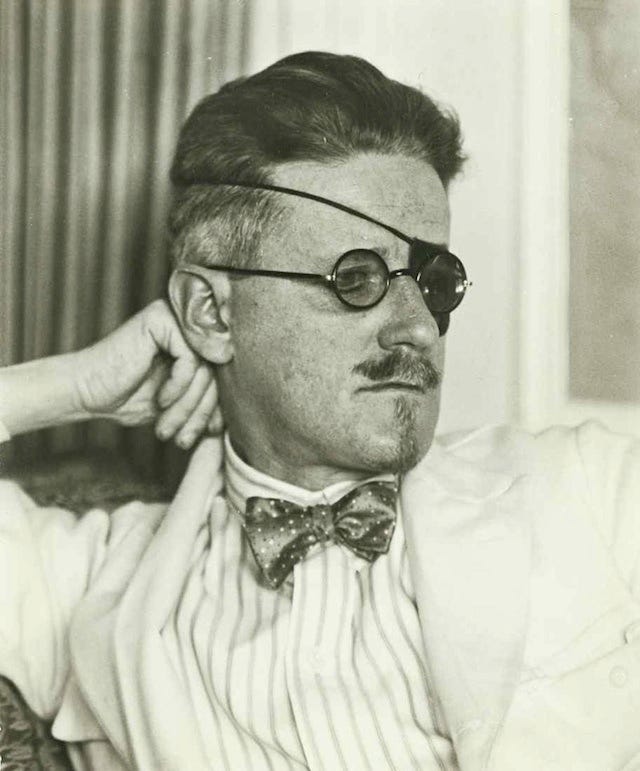

or, a portrait of masculinity as a young man; or, james joyce howled

I think I’m having a panic attack. I’ve never had one before but I’ve also never felt like this, especially from reading a book.

Churning inside me and the horrible sensation of rising vomit. My vision tunnels and I’m cast adrift aswim shoreless with language, with these sentences. I cannot think. I cannot breathe, yet I continue relentlessly onward into the furious lashing of the tides of subject and verb and winding words wailing through childhood.

His and my own.

It is my own life roaring back with nauseating acuity. But within me and my memory are no words, only the flashing visions of my past, my childhood, and the strange mix of elation and terror of watching your life refracted through experiences 120 years older.

I have read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce before but this felt like the first time.

Like the only time.

I’ve been thumbing through the pages the weeks since I tore through it, since almost throwing up into it, since these long dead words tore through me.

I spent the summer between freshman and sophomore year on acid. In between, I worked my two jobs and read a lot of books. The one that stood out to me most powerfully was not A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, but Moby Dick.

I drifted between shores with the Pequod and its crew like a drunken boat. I drank up those nautical miles of words and gobbled gluttonously on the vast carcasses of encyclopedic knowledge of the whale we all hunted, of the whale hunting always only us.

Both books felt like the kind of books I was supposed to read and so read them I did in between bouts of Faulkner and Kawabata and Abe and Mishima. But A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man sort of slid past me without calling much attention to itself.

It felt, at the time, less innovative than Faulkner's expansiveness1 and less daring than Kawabata's minimalism and not nearly as off-kilter as Abe and less narratively satisfying than Mishima.

I had been drawn to Joyce for many years, though. I’ll have more to say about this at a later date, but I have always felt a strong call from Ireland for too many reasons to bother listing here especially because none of them have anything to do with the reality of Ireland or the Irish people who were, at the time, theoretical to me.

I did not know then that in a year I’d be moving there for a year.

And so I mostly moved past Joyce and went on with words—my own and those of others—and filled my head with music and Bonnaroo and temporary romance and drugs and enough alcohol to kill me while I did my best impression of someone trying to not die.

But I dreamt of death almost constantly. When I walked the mile to my university or walked the mile back home, I imagined getting hit by cars while I crossed the residential streets. I thought about it so much that even walking those streets years later reminded me of my many imaginary dyings.

But eventually I made the plans to go to Ireland. I told my advisor2 that I was thinking of Trinity but it’s a fancy school for fancy people so I probably couldn’t go there, to which she said, “I went there,” inviting me, a regular fool from a regular place, into a reality where I could go wherever I wanted if I had the right introduction.

And besides, she wasn’t a fancy kid either.

So I sent my application and convinced people an ocean away that they should let me come spend money at their school for a year.

That was when I decided to read the famed Ulysses, and I felt my jaw unhinging opening wider and wider to swallow the entire world.

My wife has been reading books about raising boys because we’re in the process of raising boys. She hates when I ask her to summarize books but I ask her to do it all the time because I just don’t have time to read everything in the world. We did talk about what she was reading though and I found some odd parallels to the book I had just read.

Boys learn better through competition. Our schools have very much shifted away from this for what should seem like obvious reasons. But many of the ways that we’ve changed our education seems to have had some negative impact on boys.

It has been extremely successful at improving academic opportunities for girls, however.

But young men are a shrinking portion of college populations. Many young men seem cast adrift in society, which leads to all sorts of other problems that I won’t get into here3 but you hear about these issues in the news almost every week.

Another interesting bit was that segregating the sexes during education has interesting affects on boys and girls. And it seems like there may be some benefits to boys being in all-boy schools. That’s not to say that this is now our plan for our son, but it was interesting to hear about some of these possibilities and some of the potential implications of the changes we’ve made in education.

One of the benefits seems to be that boys are more comfortable, in all-boy settings, to take part in the arts in school.

When you’re one of five boys trying out for the school play, various names4 are not uncommonly heard. Even at my own high school, I remember a football coach storming into the auditorium to try to get his players out of practice for the play they were in.

This grown man called it gay.

2005 was a different time is all that I’ll say about that.

There are many pressures on boys and young men to make them ashamed for liking what they like, for being who they are. And while this isn’t exactly unique to boys and young men or for anyone attending high school, I do think the result of these pressures has far more dangerous anti-social outcomes.

The kind of stuff you hear in the news, if you follow me.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Men is about many things, but it is ultimately about growing up.

It is a rebuke of England and Empire, makes mockery of priests and the Church, but also an attack against Ireland and the Irish.

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo ...

His father told him that story: his father looked at him through a glass: he had a hairy face.

He was baby tuckoo. The moocow came down the road where Betty Byrne lived: she sold lemon platt.

As a child, Stephen Dedalus, our protagonist and stand-in for Joyce, struggles to make sense of the bewildering world happening around him. When he goes to school, he is smaller than the others and brimming with intelligence, for which he is doubly mocked. And so he muddles along and learns to play the part of his peers. At home he overhears the political questions surrounding Charles Stewart Parnell but understands nothing, for he’s only a boy in a world meant for adults.

Even back at school, where he has now found a sense of place and community with the other boys, he is treated cruelly by one of the Jesuits, and a great deal of time is spent as Stephen works up the courage to complain to the rector about it.

As he grows up, he discovers the Red Light District and begins frequenting whores. During a powerful sermon, religion rises anew in him and he devotes himself, for the first time, to the Church, to belief, to a crucified god.

All along the way, he is falling in love with words. He is falling into words. Collapsing inside them. Pulling them back into him, ecstatic at the overwhelming, overbrimming sensation of beauty, the intoxication of language.

Stephen goes to University College Dublin and gradually shrugs off the church, but also his family, his education, and even his Irishness.

And while he develops as an artist, he finds himself alienated more and more from the world. Eventually, unable to speak to anyone who understands him, the novel shifts to journal entries in the lead up to his abandonment of Ireland.

Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.

I am not an anxious person. I rarely feel anxious about anything, honestly.

I’ve never had a panic attack or anything like that.

But the anxieties of young Stephen nearly choked me. Suffocatingly real, my own life flooded through me and clouded my eyes with unexpected tears.

As he grew older and struggled with god, with church, I was once again alone in the deepest of night crying my child eyes out because of all the lack in me, the lack in gods, and the soul I was abandoning in hopes to save so many.

The feeling of shame, of alienation, of misunderstanding. The confounding confluence of people and cultures and worlds while I was only me, a large boy who people gathered around for reasons I could never understand.

I tried to love god. It seems now I failed.

Who were all these other children looking to me for leadership? Did they not know that I, too, knew nothing? I had no destination or even conception of direction.

But I discovered books and other lives where I could find pieces of myself scattered between tattered paperback covers.

I was lost. I remain lost thirty years later, and still people marshal round to lift me up, to tell them what and how and why and I look to my two boys and wonder if I can even help them navigate the childhood I never entirely grew out of.

Of who do you speak?

I felt my chest caving in at the weight of existence, at the alarming necessity of understanding. I wandered the streets of St Paul zonked out of my gourd on LSD some hippy handed me in a field in Tennessee and watched my friends and roommates swirl around me, making connections while I felt utterly outside of everything.

A sensation like the flaying of my own skin that, at the end, as the last clinging connection between skin and flesh severed, shuddered through me in near ecstasy.

I was lost. Adrift. Aswim. Aswirl. Yet I was still me. Still had me, even if there was no other.

I had sought for that other, for those others, for so long and found always my own empty hands, even while surrounded, even at the center of attention, while people gathered to hear my stupid thoughts blurting out of my mouth agape, tongue flapping and teeth clacking meaninglessly while inside I continued to drift alone, full of want and need.

Once upon a time, I believed I could hold myself together by becoming a beacon for others, that I could make myself understood by understanding them, that I would become a vessel for others to pour themselves into.

And so I did.

People told me so much. Told me everything. And I only listened without judgment and tried to help them understand themselves, because, maybe, if I could lead them towards themselves, I would find the people I needed.

I’ve read little and understand less.

I lived inside books for years because I was unable to find what I needed in the people around me. I found great beauty and power and an overwhelming sensation of life even while I sat in my bed staring at pieces of paper smattered with ink. And so I fell in love with Dostoevsky and cried my way through Crime and Punishment twice in the same week and then two more times in the coming months, underlining nearly every sentence. When it was my turn in class to present, my essay was nearly twice as long as the recommended length but I could see nothing worth cutting, nothing that I could cut without losing it all, without losing the self Dostoevsky forged in me.

And I wrote about Svidrigailov so lovingly, so heartbrokenly, and was rewarded with the highest possible grade, yet even then I found myself misunderstood or, rather, un-understood.

Ununderstandable.

Could not find my Sonya, my salvation, the one who would make me, finally, human.

And I crossed an ocean to escape my own disappointment, my own shattered heart, and I looked everywhere for something to fill me, for someone to make me whole, but I found only ever the hole inside me, inside us all.

The hole that I sank down inside, curled fetally, and listened to the murmur of the earth, the trembling of my own abandoned soul, and when I looked up into the golden bluing sky—

I could not find the words. Could not find the person I believed could make me whole. And so I gave myself to my own words and the words of others. I spent miles and meals to go to the used bookstore and fill my bag to fill my head and my heart with money I didn’t have, with money borrowed and lent.

Are you trying to make a convert of me or a pervert of yourself?

And when I returned home from Ireland, still broken, but full of newness, of experience, of a longing for more than I ever thought my life could possibly be, I made plans to abandon my life once more, especially when I found that the hole inside me was following me.

But first I gave myself over, once more, to words. To finding and forging beauty, to wonder, to the wonder of the sea coming in at midnight while I gasped on those St Paul bluffs counting our ecstatic numbered days until I danced along the rubicon beach while the tours of the black clocks swarmed round me like days between stations all leading me, inexorably, towards my own private zeroville.

My roommate, at the time, understood this about me, though I didn’t understand that he understood.

He told me quite simply that moving would not solve my problems or make me the artist I believed I wanted to be, because I would still be me, dragging my ghosts and my dead and my heartbreak along with me, chained behind me.

I said I lost my faith not my self respect.

I went farther this time. Not across just an ocean but across to the otherside of the planet. I moved to Korea and found that the hole inside me was chasming and that if I didn’t learn to fill it up, I would drown in it, suffocating on mouthfuls of earth.

I neither believe in it nor disbelieve in it.

And so it was that a year of joy and trembling fear and suffocating need ended with a sense of loss, of pain, and though I was finally writing the words I always meant to write, dancing along my keyboard for hundreds of thousands of words, reading countless books, and discovering that the world was both larger and smaller than the child I once was, I also plummeted neverendingly inside myself.

This brought me back to Europe where I met the person who would change my life, who would give me a life.

And, at a certain point, this need in me has shrank. I still often feel alone, even in a crowded room, even when a dozen people are listening to me speak my stupid thoughts into the senseless air between us, but I find that this hole has not been the terrible lack I always believed it was.

This hole in my life, this void in the world.

It’s mine.

It’s a part of me.

It is me.

blame chronological time

interesting to watch her Ted Talk, which is about sleep, for reasons that may become obvious to regular readers here

I could!

a certain slur, for example

The consolations of great literature parallels our personal experience and you build on literature with clarity and perspective. As a Catholic young woman attending a Jesuit university Joyce gave me much to consider. For our side of the aisle there is Edna O'Brien.

This caught my attention likely because I read Ulysses as a teenager far from either of my parents while in a school populated with teachers who were dissatisfied writers slumming in Greece and more or less grudgingly teaching at a private school for kids they largely resented. My freshman English teacher - who like the others had his doctorate and was always hung over, had (he said) once gone drinking with Dylan Thomas. I liked him. Another worshipped Faulkner (which I endorsed), another was a snarly biblical scholar coming to terms with his bisexuality (who i admittedly had a crush on). He drove an MG. But I digress.

Bottom line several worshipped Joyce. Hence my older sister gifted me the book. Hence me determinedly plowing through it, expecting an epiphany, the presence of a boy named teddy in my grade who perpetually had his hand in his pants probably reduced any shock I may have had over Blooms behavior. (I did enjoy D.H. Lawrence, who is in my opinion a greater writer, and not because of the often tedious Lady Chatterly. His societal observations were more worthy to me than Blooms frustration over his marriage.)

But I revisited Ulysses in my thirties - willing to look again, and can definitely say (out of my ignorance of greater themes perhaps) it gave me a headache.

I’m someone who still has my unabridged copy of Moby Dick filled with my 13 year old scribbling - that my children used when they were assigned it in high school. Melville’s Barnaby still holds my heart.

I concluded what we all suspect: Some ‘great’ literature isn’t. And I’m sharing that epiphany, not as a scholar but as a reader. Ulysses to me stands as an exercise driven by Joyce’s large ego, purposely obscure and often tedious because Joyce was insufferable.

So that’s my Ted talk. (And I mean that weird kid I knew in high school)