Christopher Nolan announced that his next movie would be the Odyssey and I cannot think of a worse director to adapt this ancient poem, but no one asks me who should make movies out of what poems so here we are. It is fitting, I suppose, with Nolan’s interest in ideas over people, but only broadly. I could go on about this but I want to talk about a bit of a hullabaloo that this stirred up.

People online began discussing The Odyssey and while, apparently, many people have never heard of it1, many more began discussing the merits of various translations.

The villain emerged and it was Emily Wilson. Since I’ve an interest in ancient poetry and various translations of them2, I thought I may as well comment on this here, especially since I read Wilson’s translation a few years ago.

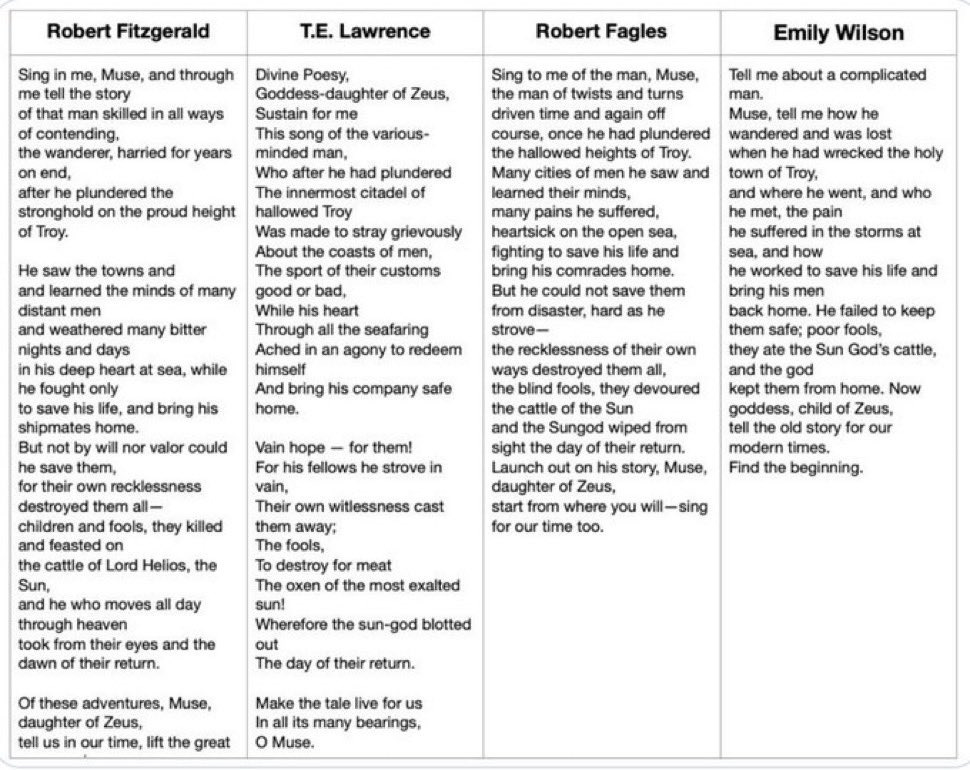

One way—and a pretty useful way—is to compare like with like, and some enterprising net denizens did just that with the opening of The Odyssey:

Now, you’re allowed to feel however you like about these four translations and if me writing about The Odyssey finally causes you to pick it up, the world will be a better place for it. And I encourage you to pick up whichever of these four that feels most enticing.

Controversially, I think Emily Wilson’s translation is a good place to start. Of course, this is assuming you’re the type who would read multiple translations of the same piece of work for fun. I mean, who would do such a thing?3 But, you know, even if you don’t plan on reading another translation, I will still recommend Wilson for a simple reason:

It’s the simplest to read and follow.

It really is like that. I think there’s value in reading the poem simply for the sake of understanding what Odysseus did, where he went, why, and on and on. If you’re more interested in the tale than the telling, the Wilson translation is the perfect place to look.

Some lit majors or classics scholars may be gearing up to yell at me but if you’re the casual reader of literature who has, perhaps for the first time, shown an interest in ancient poetry, this is as good a place to start as any.

A big benefit of the Wilson translation is her Translator’s Notes, which, if memory serves, stretches over nearly 100 pages.

If you’re a casual reader, you’ll probably skip right past this and realize you’re already a quarter of the way through the book, which feels nice. But if you read the book and double back to this, there is a lot to feast upon.

This really is the best part of the book, and I’m not being snide or glib when I say that. Reading how a translator made the choices they made with this much detail is truly fascinating, especially if, like me, you’ve an interest in language and translation and so on.

Just from looking at the comparison above, something should be immediately clear about her translation: it’s briefer.

This is because she aims, on purpose, for simplicity and plainness. According to her, the High Register we associate with ancient poetry does not exist in the Greek. I have no way of judging this so I take her word for it, but because of this she also chose to transpose the poem from its original meter to iambic pentameter, since this mimics closely spoken English and is the kind of poetic meter English speakers are most familiar with.

There are few, if any, translations that mimic the original Homeric meter, so this is not exactly that notable. Each translator picks his (Wilson is notable for being the first woman translator of the epic) preferred meter or at least the meter he believes best serves the poem, and many translations forego meter entirely. However, we do see how different it is from the other translations.

What Wilson is aiming for here is a bit of reclamation of the original intent. These poems were sung over the course of communal evenings. They were a performance. And in being a performance, the communication was important. And so the language was relatively unadorned and clear and straight forward.

Allegedly. I don’t and cannot know because I don’t read Greek, ancient or otherwise.

I do think Wilson achieves this and her Odyssey is clear and straightforward and simple to follow. It’s also quite often clumsy and artless.

For all Wilson’s scholarship, she is most certainly not a poet herself. Or perhaps she is, but she’s a very poor one.

And so I understand the critiques and dismissal of Wilson’s translation.

It’s often quite artless!

Is it bad? I don’t know. But the poetry of Homer as mediated through Wilson is quite bad. It would not have survived the ages, I think, if Homer was so clumsy in his telling, in his metaphors, in his lyric.

Even from the first line, this is apparent.

Tell me about a complicated man.

I cringe. I wince. I nearly double over, clapping my hands over my ears. Rarely do I encounter poetry that breaks my poor brain apart like this. But, out of curiosity, I went on and on and made my way through.

But if you’re looking for a more artful telling of this poem, you should pick just about any other translation, though I’d still recommend picking up Wilson’s just to read the Translator’s Note. It really is that good.

Taste being what it is, I cannot tell you which translation to read. I’ve read a few and it seems like the award winning Fagles version has become the preferred one though Fitzgerald’s was the standard for quite a long time.

If there’s anything good about these literary squabbles, I hope it’s that more people begin diving into the ancient past for their poetry.

Free books:

Always remember that the people talking on the internet might be eleven or simply illiterate adults who cannot fathom stories disconnected from some conglomerates IP

I abandoned my plan to write about Beowulf last year but perhaps it’s time to do it, or at least give a bit of a rundown of various translations and why you should or shouldn’t read them

me, and I’ll tell you why right here where no one is likely to even see it.

Perhaps because Wilson is who she is, and the current linguistic restraint practiced by many, the traditionally masculine and chauvinistic language used in Homer's original and preceding translations needs to be modified. This is not uncommon in dealing with literature from earlier times, since new translations continue to emerge that approach the works from very different perspectives.

The translation I read for a college course was in prose, if you can believe it! The translator chose prose deliberately because, as you note, no translation replicates the meter of the original Greek, and he wanted to emphasize the meaning rather than the sound of the words.

Even though my favorite translation is Fagles’s, I am actually a fan of translations that resist the high register and try to replicate the original experience of hearing the story as an entertaining tale, before it became GREAT LITERATURE.

Thanks for the push to read Wison’s translation!