Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone

or, the humble beginning to a series that changed the world

Harry Potter has become such a cultural juggernaut that it’s difficult to really talk about the books without talking about a dozen other things, but I really do want to try to just talk about the books as books, because, for better or worse, I’m of the opinion that we should deal primarily with the art itself when critiquing art.

But it is worth discussing the phenomenon of Harry Potter at least a bit right here at the start of this endeavor.

Harry Potter very quickly became controversial because Christian conservatives believed it promoted witchcraft and wizardry, which was a pathway to satanism and so on. This was the same reason my parents made me burn my Pokemon cards around the exact same time, mind.

Its astronomical popularity among the young and old also led to various publishing disputes over awards and what should be included in the bestseller’s list and on and on.

Back in the late 90s and early 2000s, hard as it is to remember, Harry Potter was an underdog. The little book for kids that was slowly coming to dominate literature, whether anyone liked it or not.

Eventually, this resulted in many people making Harry Potter their whole worldview and tying their personality so tightly to the series that they seemed arrested in time, forever the child they were when they first picked it up. In the lead up to the 2016 election, for example, you had grown adults parsing the election of Donald Trump by invoking the bad wizards from a children’s book.

And then, of course, JK Rowling began talking about trans people, which, as far as I can tell, is a grand unforced error made by a wealthy and powerful person which led to her burning down all the goodwill and admiration she’d spent the previous 20 years courting online.

Before she became an internet pariah, many liberals seemed to think of her as a model for inclusiveness. Her twitter was used, as far as I could tell, to respond to fans who wanted to know if different identities were represented at Hogwarts, and she unfailingly told them, Uh, yeah.

And, of course, she famously announced that Dumbledore was gay which caused conservatives, once again, to scream foul and for liberals to congratulate her on her broad mindedness, despite never making that an aspect of his character in any of the six books he appears in. And, I mean, we shouldn’t expect every character’s sexuality in every series—especially one written for children—to be demonstrated on the page or on the screen, but it always felt weak to me to just add it as an afterthought after the series ended.

I’ll just say this plainly: I have never liked Harry Potter.

I also began despising Rowling when she lobbied against Scottish Independence in 2014.

I found the way people made Harry Potter essential to their identity embarrassing when I was fourteen but especially when I was twenty-four. I think adults who put things like Gryffindor House in their online dating profiles should have been very embarrassed of themselves even before JK Rowling made herself an internet pariah.

But, like I said, I intend to deal with these books for what they are, not for what we’ve all made them into. And, for me, that means memory palacing my way back to who I was twenty plus years ago.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone came out when I was ten—the same age as Harry himself—and I dutifully ignored it for several years because I was a Lord of the Rings kid, not a Harry Potter kid.

This probably sounds like a silly demarcation now, but it meant a lot when I was a child! Some of my best friends were obsessed with Harry Potter, but I was already deep into the Appendices of Lord of the Rings and even onto The Silmarillion.

Of course, rather than engage with the texts the other person championed, we just dug our respective trenches and I quietly told anyone who mentioned Harry Potter that it sucked.

Kids, man.

When the fourth book came out, I finally decided to pick them up and even though I tore through all four of them in a relatively short time period, I still didn’t like them much. Yes, they were better than I had led myself to believe, but they also simply were not The Lord of the Rings.

They weren’t even The Hobbit.

But they also weren’t trying to be. I have little memory of these first four books now, but they didn’t leave much of an impact on me even back then. I read them rapidly when I picked them up from the library, but I also didn’t pick up another Harry Potter book for about a decade.

When people obsessed over Harry Potter, I stopped being rude about it but I also didn’t have much to say. By this time I was no longer really reading books targeting my age bracket. While I enjoyed Ender’s Game (another problematic author, as it turned out) when I picked it up, it was really Speaker for the Dead that gave me my first brutally strong emotional reaction to a novel. I dabbled in Dickens and Grahame Greene and picked up Dracula and so on. I discovered Asimov and Hemingway and eventually Virginia Woolf and on and on.

When the fifth movie came out around the same time as the seventh book, the immensity of the Harry Potter hype finally got me to go to the theatre to see the fifth movie and borrow the fifth, sixth, and seventh books from a friend. I didn’t bother rereading the first four because who cares, but I dove right into the second half of the series.

They were pretty good!

I couldn’t tell you much about them now, except for what I learned when watching the movies a few months ago.

But I read them rapidly as well and was able to enjoy them, despite the fact that I was deep inside Virginia Woolf, William Faulkner, James Joyce, and other acclaimed and noteworthy authors of difficult books that most people don’t bother reading anymore.

Even so, in the intervening decade, I have thought very little about Harry Potter beyond my general annoyance in how pervasive it was for adults to use Harry Potter as a way to explain their life to themselves.

I mean, it still does annoy me! Describing Robert Mueller as, like, the professor for the defense against dark arts was cringe inducing for dozens of reasons.

But passively watching the movies a few months ago while my wife and I spent dozens of hours playing Crusader Kings III (more on this someday) filled me with a kind of fondness for this world and I got the idea that I might like to read the books again.

Now that I’ve blasted through the first book for the first time in about twenty years, I must say that this book is, you know, pretty all right.

It’s funny, in a way, that this little story about an abused boy discovering that he is the chosen one should become the cultural force it did.

There’s a Dickensian quality to it, what with the racial caricatures, the funny names, and the instantly identifiable stock characters. It’s a book without complexity, but that’s okay.

The book is for young children.

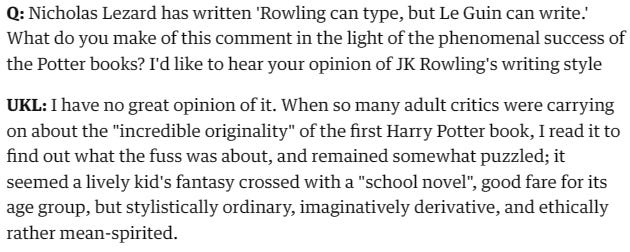

Like Dickens, there is a meanness to much of the characterization. Even the introduction of the Dursleys has a level of spite and condescension. It works quite well for the novel, but it does drive home Le Guin’s point here.

The worldbuilding leads to a very specific kind of class stratification and justification for elite rulership as well.

But we’ll get to that in future books.

This first book does delve into bits of darkness that I think appeals to far more children than most adults are comfortable with.

My own son loves monsters. He loves vampires. He’s curious about death.

I mostly wish this didn’t remind me so much of myself, but we can talk about my fatherhood fears some other day.

The novel has a funny shape to it as well. The first half is almost all introduction. We’re slowly learning more and more of this wizarding world without actually learning too much. It’s a funny feeling, honestly, to have information coming at you at a pretty fast pace but not really know that much about anything.

The worldbuilding is paper thin, but that’s all right. Like I said, this isn’t aiming to be Tolkien. It’s not even aiming to be Earthsea (though do I have thoughts on this! but they extend back on to Rowling herself, and I’ll leave that alone for now).

It’s a fun little novel about a boy who goes to school to become a wizard. Along the way, he makes friends and enemies, and even discovers a very silly sport of which he is a prodigy! Quidditch is one of the funnier and cleverer things Rowling does here.

The explanation of the game is hilarious and I believe this is on purpose as a parody of the arbitrariness of rules that go along with any other sport. The sports we know seem so natural to us, but I imagine if I explained the rules of baseball to an alien, they would be baffled in dozens of ways.

The book is full of clever little touches, really. Hermoine beginning as an annoyance who slowly develops into an important friend feels the way many friendships grow. We’re often friends with people for no real good reason except that we spend a lot of time together or because we’re already friends.

Even Harry and Ron’s friendship starts for no good reason except that they’re kind to one another upon first meeting, whereas Draco is, from the very first meeting, an asshole.

This is also the moment we begin to see the analogy for racism and the implicit justification for what aspects of the series seems to want to argue against. But, again, we’ll get there as the series goes on.

It is interesting how little we know about anyone in the book and how little we discover. Almost everything we learn about Ron is explained upon his introduction, and the same is true of Hermoine and Draco and Hagrid and Dumbledore and on and on.

Rowling introduces them with broad enough brushes that we recognize them instantly for the archetype they are and then she moves on, only bringing them back into the narrative to reinforce that initial archetype.

To put it another way: no one surprises us in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Even the conclusion of the novel, where Quirrell is the antagonist rather than Snape, falls neatly into place without too much explanation.

But back to the shape of the novel: it’s very odd! It seems to mostly wander along without much thought for a central conflict until we’re about 3/4th of the way through the novel when we better get on with it.

Where the first half of the novel takes up just a few months, the remainder of the novel covers the bulk of the school year, which whips by us as Harry, Ron, and Hermoine study, investigate mysteries, get in trouble, and so on. Little time is spent in any of the classes beyond their introduction and little time is spent filling out the school or the wide cast of characters who will eventually populate the school.

But this tight focus is a benefit, as is the structure of the mystery.

I’ve mentioned this before when discussing George RR Martin, but there’s a real trick to making the reader feel smart. Rowling does this better than most, honestly, and it’s helped that she’s writing for bookish young children who are already predisposed to overvalue their own intelligence.

She gives you enough information at just the right pace for you to unravel the mystery pages or even just sentences before someone in the book announces the solution to the puzzle.

And so the reader—in this case, a bookish child—is rewarded simply for understanding the book that they’re reading.

It may sound like a little thing, but it’s probably at least one ingredient in the secret sauce that turned Harry Potter into the billion-dollar multimedia product it became.

And it all begins here, so humbly, with a boy kept in a closet trying to be a boy worth loving.

That last bit is another ingredient to the Harry Potter secret sauce.

Anyway, to sum it up:

I sure did read this!

What’s perhaps most surprising about this first book is how unremarkable it is. It does, oddly, make me more excited about this reread.

I mean, imagine how boring it would be to discover as a 35 year old that this was my new favorite book?

But I’m fascinated that this book blew up the way it did to become, in under 30 years, one of the bestselling books in history. Also, worth noticing where all seven of these books fall on that list.

The Chamber of Secrets review is coming at the end of the month.

Colony Collapse is still $0.99 until Thursday and Howl is still $0.99 until the end of the week!

These sales continue for the whole month, however:

Your prose style sounds more British to me when you are writing about Harry Potter. I don’t know if it’s me or you, or what to to make of it.

Libraries benefited greatly from HP. No, it's not LOTR--I'd say more like the OZ books, but if a saga grips children it did establish a love of reading in that generation of children.