No one asked for it. No one needed it. No one even wanted it.

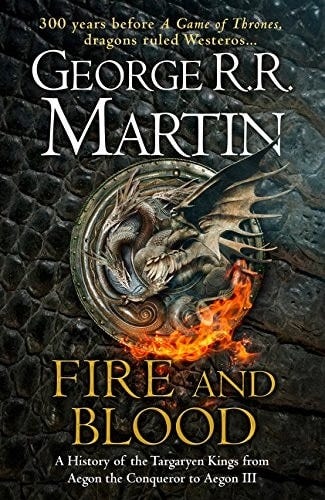

But George RR Martin wrote the first half of his history of the Targaryen Dynasty and it is great. It is great in all the numerous ways that it is not The Winds of Winter—the book everyone wants—and for all the ways it refuses to be a novel at all.

If you’d like to catch up on this series wherein I’ve accidentally spent the year dealing with Westeros, you can follow these helpful links:

And if you want to know what I thought about the TV show based on the book I’m about to write about, you can follow these ones:

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s get down to it:

Fire & Blood gives us everything we never wanted in such luxuriously luscious detail that we eagerly gobble it down like the gluttonous little goblins we are.

When writing about A Game of Thrones, I talked about how Martin had already spent a career not writing massive epic fantasy, which prepared him to perfectly execute his own subversive epic masquerading as Tolkien pastiche. Over the following almost-thirty (!) years, Martin has managed to lose track of his narrative as it unspools hilariously out of control, yet he remains a writer at the peak of his ability.

Martin is one of our most flexible writers. His prose is rarely showy, but it is always appropriate. He’s telling a complex, complicated story with hundreds of characters - best to keep the sentences relatively straightforward. Even so, Martin uses a lot of techniques and stylish touches to make his many perspectives unique enough to avoid confusion. The style is never so pronounced as to distract but it’s always enough that we can immediately know if we’re in a Sansa, Arya, Catelyn, Daenarys, or Cersei chapter.

That may seem a small thing, but it really isn’t. As Hawthorne once said: easy reading is damn hard writing.

But more than the ease of readability, what we find in Fire & Blood, his massive history of the first 150 years of Targaryen reign, is something new. Something rarely attempted by anyone—for good reason!—because of the inherent difficulties of the genre within the genre.

Just last week, I reread The Silmarillion for the first time in many years. It is still my favorite Tolkien book, but it is also a troubling book for even die-hard Tolkien fans. Less a novel than a collection of myths punctuated by a few novellas that all lead to a rather obscure resolution.

Fire & Blood is also not this, though. It’s not a novel and it’s not a short story collection or collection of myths. Instead, it is meticulous history. Imaginary history told from the voice of a scholar in the world of Westeros, communicating this history to other people within this world.

It is, perhaps, one of the most postmodern fantasy books available in print. That it has been read by millions and will be read by millions more—especially after the success of House of the Dragon—makes it even more astonishing an achievement.

The demands of writing a novel and writing history are very different. For one thing, characters come and go much swifter in history than in a novel. Had Martin wanted to, he could have turned this history into fifteen separate novels. The Dance of the Dragons—which takes up the biggest portion of this book—could easily take up its own seven volume fantasy series. And yet, here he captures the entire epic in a few hundred pages.

But this is the flexibility I’m talking about. Not only is Martin writing in a genre that he may as well have invented for this book, but this book, rather than being dry history, is a rollicking good time. It’s sometimes funny and sometimes quite touching, despite the academic remove and the lack of interiority of its many protagonists churning through the decades of dynastic struggle.

Martin is always interested in the political. Famously, he started writing A Song of Ice and Fire in reaction to the end of Aragorn’s narrative in The Lord of the Rings, wherein Aragorn takes the throne and we are told that he is a good king for nearly a century.

Martin wryly mused, What is his tax policy?

Well! Fire & Blood goes there. Yes, it’s a story of conquest and war and it is a multigenerational story about a family at the height of power, but it is also the story of how a kingdom gets built and maintained. Perhaps the greatest strength of this book is that it balances these many threads so well, so entertainingly. Martin gives us the political, but also shows us how often the political is rooted in the personal. How often good land management is also a political declaration, how taxation can be a personal insult or placation.

Like A Song of Ice and Fire, everyone in Fire & Blood has their own motivations and all these motivations and goals compete and clash, which keeps the different monarchs much more fascinating.

Aegon conquered Westeros with dragons and solidified his rule through violence. But, once solidified, he went about building his realm and tying it together through blood and friendship. We see in his descendants how they fail to do the same thing or succeed and even surpass what Aegon set out to do.

And all along, Martin keeps us moving. Keeps us fascinated. He can’t use the tools of a novelist because the life of Aegon, for example, comes and goes at an alarming speed. The conquest of Westeros and the subsequent decades of Aegon’s rule could be its own trilogy. Instead, it’s maybe a hundred pages here.

Martin must use the techniques and methods of the historian to tell his fictional history. And while histories are not everyone’s cup of tea—though they should be!—Martin does what the best historians do, which is capture, in snapshot, the many personalities of an age and use these personalities to explain the context of a war or political tussle or even explain how a dynasty turns to infighting at what appears to be the apex of their power.

Interestingly, I’ve read versions of some of these before. In various places, martin had published novellas of Targaryen history (The Dangerous Women Anthology, for example), but I always found these to be rather dry and lacking flair. In many ways, they were what people feared Martin’s histories of Westeros would be.

But in the intervening years, Martin cracked the method to make this work.

The dragon in the room, of course, is that no one wanted these histories. But rereading A Song of Ice and Fire, it’s clear to me that Martin’s interest in that narrative began to wane as his interest in Westerosi history expanded. While the first three novels touch on history and what came before, books four and five really deepen and broaden this history. We learn more about Targaryen history in A Feast for Crows than we did in the first 3,000 pages of the series, for example.

And it’s even possible that, to Martin, he had to pin down this history in order to finish The Winds of Winter and The Dream of Spring.

History informs and defines the shape of the present and future. For a series structured around a young hero reinstalling her family and refounding its dynasty, it makes perfect sense to me that Martin felt he must go back and nail down the larger Targaryen history before he can successfully move towards the endgame.

It’s helpful that House of the Dragon reinvigorated everyone’s interest in this world, because the highlight of this history is the Dance of the Dragons. The ways it differs from the screen adaptation are interesting and maybe I’ll talk about it some other time, but I think this part of the history is where Martin gets most clever.

Martin’s narrator and writer of this history often references the historical accounts he’s relying on to tell this definitive history, but The Dance of the Dragon goes deepest into this process. See, there are three primary accounts. One, by the royal fool named Mushroom. His account is deemed most unreliable as it is also the bawdiest, describing a court of debauchery, violence, and insipid and petty infighting. The other two accounts, deemed more reliable, are by previous historians.

The fun here is that it makes our narrator most clearly seen as unreliable, pushing the postmodernist tendencies yet farther.

But the contrasting perspectives that are being pulled from to relate this history gives us sometimes very different versions of events. While Mushroom is often dismissed, our good Archmaester also includes his accounts. Possibly just for the color and humor of them, but also, I suspect, because our genteel historian believes his account the most, but propriety demands he qualify every inclusion.

At any rate, this internal tension gives a wild texture to the Dance of the Dragons, the bitter civil war that nearly destroyed the Seven Kingdoms.

And though we never lose or move away from the scholarly tone, we feel the emotions as if this were a novel. The bitter enmity between two branches of the same family feels alive and reckless, and we despair at the death of every dragon, of every child murdered.

We even feel a sort of beautiful resignation in characters who began as terrors.

This, by itself, is quite the achievement!

Especially as it follows the long reign of King Jaehaerys, who also took the reins of rule after another calamitous familial civil war. Jaehaerys feels like a hero. The classical Good King who binds people together through wisdom, strength, and charisma.

That his long reign leads directly to the collapsing of his own house feels tragic, and during his long reign, we come to love him, in a way. We appreciate his ability even as we see how his ability to bind a kingdom together does not translate in him binding his own family together.

Then there’s Viserys, who I loved so dearly in House of the Dragon, but who is barely even present on the page here. But I suppose I’ve said enough about Viserys, shed enough tears over him.

What Martin has done with Fire & Blood is give us everything.

He has given us all we never knew we wanted and he has given it to us so exquisitely that you almost have to read it. Especially if you love this world, as I do. Of course, if you want to avoid spoilers for House of the Dragon, you definitely should not read this. But spoilers are for babies.

Quit being a baby.

And so, yeah, I’d say this is worth reading.

Well, I did not intend for 2022 to be The Year of Westeros, but I spent tens of thousands of words writing about Westeros. First, A Song of Ice and Fire. This happened to lead straight into House of the Dragon’s premiere and run. Having fallen in love with that show, I couldn’t avoid this book about the Targaryens, even though I’d spent the last four years not interested in it.

This series on Westeros and Martin has been less successful in terms of readership than I’d have hoped. This isn’t surprising and a smarter person would have pivoted to a project with wider appeal, but I am who I am and I do what I do, and I had a lot of fun doing this.

So I may do it with some other series next year. Possibly I’ll be reading Harry Potter, because I got the itch to revisit these things. But I also got into a bit of a discussion about how I think The Last Jedi is the best Star Wars movie, so I may watch all the Star Wars movies and write 30,000 words just to prove to everyone that I’m right.

I’m also considering revisiting Malazan Book of the Fallen by Steven Erikson (not to be confused with Steve Erickson), but if A Song of Ice and Fire is of niche interest, this is doubling down tenfold on that idea of diving deep into things my readers are unfamiliar with.

Or maybe some other series I haven’t considered! So if there’s some series of movies or books or TV shows that you’d like to see me spend the year writing about, let me know. Extra points if it’s something easily available on a streaming service I already subscribe to.

I really want to read Fire and Blood now. Also, I would love to read your take on the Last Jedi. My favorite SW movie of all time. Super underrated. I have a lot to say about it myself.

Fiddler, Quick Ben, and by all that is Holy TAVORE. BRIDGE BURNER til that day friends. Nuff said.