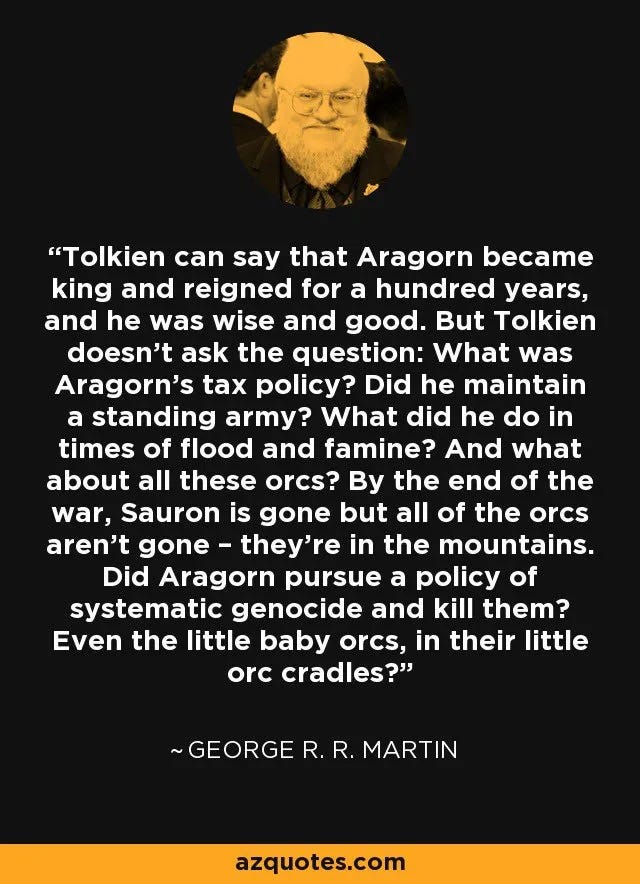

Um, no. Obviously. This shouldn’t even need further explanation, but this temporary controversy keeps sloshing around the internet, and since I spent a year mired in Martin, I suppose I may as well say something about this quote people are losing their shit over.

For those wondering what I mean by mired in Martin, here are a list of my pieces from 2022:

And the weekly reviews of House of the Dragon:

If you read this and thought to yourself, “What’s controversial about this?”

Congratulations!

You’re normal.

Martin said this twenty or thirty years ago and everyone has understood it the same way for these last few decades. But the internet being what it is, this has now become controversial.

But Martin is not making a value statement here or even one of judgment. He’s not saying that Tolkien’s books are bad or failures or that they’re not worth reading. He’s definitely not saying that they should have included Aragorn’s tax or reconciliation policy.

He’s making a very normal statement that could be summed up as critical analysis. He read The Lord of the Rings and found himself asking very specific questions that he was interested in knowing more about, but that Tolkien was not interested in.

Some of you reading this now are writers or aspiring writers and you likely have a favorite author or a favorite book that you consider essentially perfect. But if, at the same time, you don’t see things you would have done differently, I would say that you likely have nothing more to say in this genre.

Which is also fine.

That doesn’t mean the genre is dead or there’s no more room in it, but that you, specifically, probably have nothing new to add to it.

For example, I’ve written tens of thousands of words about Martin’s world. I only did that because I sure do like it a lot. But when I first read it, I found myself asking very specific questions and found myself daydreaming about very specific things. Like what would this massive civil war mean to a farmer or one of the denizens of Flea Bottom.

This led directly to me writing an entire 100,000 word novel published in 2014, which will be re-released this May.

Martin’s A Song of Ice & Fire lit my brain on fire with possibility and I’ve spent the last fifteen years writing about these things that he left out. Martin is very interested in nobility and the games of power that are politics.

I’m more interested in the common person.

So when I ask you, What did Renly’s campaign mean for farmers on the Reach? or what Robb Stark emptying the north meant for a maid in Winterfell? or what Tywin’s policies meant for a cobbler in Flea Bottom?

I’m not making a value statement.

I’m showing a narrative preference.

I love A Song of Ice & Fire. But if I were to write it, it would be very, very different.

This is what Martin’s quote is saying about Tolkien.

He’s not saying that these books are bad or anything even remotely similar. He’s saying, Had I done this, I would have focused more here.

In fact, we know Martin admired Tolkien greatly. The RR in his name is a direct homage. He’s also open and honest about how The Lord of the Rings lit his own brain on fire with possibilities, how his own series would not and could not exist without Tolkien.

More recently, in 2019, Martin said something similar to the above again, but he prefaced it with this:

Tolkien, of all the authors I mentioned earlier, had an impact on me, but Tolkien is right up there at the top. I yield to no one in my admiration for The Lord of the Rings – I re-read it every few years. It’s one of the great books of the 20th century, but that doesn’t mean that I think it’s perfect. I keep wanting to argue with Professor Tolkien through the years about certain aspects of it.

Further, he’s said things like this repeatedly throughout his career:

I revere Lord of the Rings, I reread it every few years, it had an enormous effect on me as a kid. In some sense, when I started this saga I was replying to Tolkien, but even more to his modern imitators.

He went on to say how the imitators of Tolkien tarnished the genre Tolkien created:

But they cheapened it. The audience were being sold degraded goods. I thought: “This is not how it should be done.” Writers would take the structure of medieval times – castles, princesses, etc – but writing it from a 20th-century point of view. I wanted to combine the wonder and image of Tolkien fantasy with the gloom of historical fiction.

More at the 2014 interview from the Guardian.

You can watch him say more in the PBS series Great American Reads:

In a sense, what Martin is asking up above is: What happens when a figure like Aragorn wins his war but is not prepared for the throne?

Robert Baratheon is a great warrior. He’s unmatched on the field and may be the greatest warrior of his lifetime. And he had a strong claim on the throne—or at least strong enough.

But he made a terrible king because he was not actually interested in the difficult job of rule. This was compounded because of the webs of politics, of familial obligations and relationships that were required for him to take the throne.

Tolkien was not interested in these questions and so the Lord of the Rings doesn’t deal with them. There are gestures towards politics, but if you take the volume of words focused on politics from just A Game of Thrones and compare them to the volume of words Tolkien spent on politics across the entire Lord of the Rings, you’d begin drowning in Martin’s political jockeying.

At the same time, if you added up all the songs and poems from Lord of the Rings, you’d have a healthy poetry collection that stands on its own, whereas Martin’s poems and songs might fill a few pages.

This is all about perspective. About narrative preference.

But let’s go a step further into specificity:

Martin writes a lot about feasts. He uses these to tell us a lot about the world.

Tolkien wrote over 60 poems and songs for the Lord of the Rings to fill out his world.

Neither of these are essential narrative elements but both writers found them important enough to spend quite a lot of time on. This tells us a lot about them as writers.

And we could make a value judgment about these things, but I think that’s really missing the point of both works.

Martin admires and admits how much he owes to Tolkien, just as Tolkien admired and admitted how much he owed to Lord Dunsany and the Gawain Poet and the writer (compiler?) of Beowulf.

This is all normal and uncontroversial.

took a more headfirst approach to this controversy, which is worth giving a look if you’d like a deeper look at how defenders of Tolkien respond to what Martin said. Though, again, I don’t think Tolkien needs a defense since this statement was not an attack.My novels:

Glossolalia - A Le Guinian fantasy novel about an anarchic community dealing with a disaster

Sing, Behemoth, Sing - Deadwood meets Neon Genesis Evangelion

Howl - Vampire Hunter D meets The Book of the New Sun in this lofi cyberpunk/solarpunk monster hunting adventure

Colony Collapse - Star Trek meets Firefly in the opening episode of this space opera

The Blood Dancers - The standalone sequel to Colony Collapse.

Iron Wolf - Sequel to Howl.

Sleeping Giants - Standalone sequel to Colony Collapse and The Blood Dancers

Broken Katana - Sequel to Iron Wolf.

Libertatia; or, The Onion King - Standalone sequel to Colony Collapse, The Blood Dancers, and Sleeping Giants

Noir: A Love Story - An oral history of a doomed romance.

Some free books for your trouble:

Much of literature is based around new generations of writers either rejecting the models provided by older writers or modifying them to suit new purposes. This would be a case of the latter.

Tolkien and Martin are two different kinds of writers. The former's writing is informed by his work as a scholar of old English language and literature, while the latter's is more directly inspired by a lot of the pulp fiction he read when he was young. So naturally their approach to the fantasy genre will be different. Tolkien virtually invented modern fantasy; Martin is doing it his way.

And it's not just with literature where this occurs. My own fiction is strongly influenced and informed by the animated films and television programs I have seen, specifically in retrofitting favorite characters for new environments and genres.

Inspiration is a wonderful thing. It lights up the imagination, gets that internal flame burning and, in the right person, can produce some fantastic results. I will admit that I'm not the biggest fan of Martin's work. I read the first Ice & Fire book about a decade ago during downtime on my honeymoon. Tore through the book pretty damn quickly, too, finishing it in about three, maybe four sittings across the two week trip. Unfortunately, the second just didn't have the ability to grab me. Try though I might, especially since I did enjoy the show at the time, I just couldn't make the same kind of connection in the second book that I did in the first. I put it down after three, maybe four chapters, (I don't fully remember how many) and never went back.

However, I've experienced the exact form of inspiration he's talking about multiple times in my life. Arguably the most notable instance of this was when I watched "Prey" two years ago and, by the end, found myself deeply disappointed that the writer and director failed to recognize how the Predator operates based on how the species is presented in the original 1987 movie and the 1990 sequel. That directly lead to me finishing the first novella I released here on Substack, The Demon from Beyond the Stars, which was my own answer to how more primitive peoples would deal with a creature like the Predator.

Similar inspiration struck me again about a year later, when I read the complete collection of Elric of Melniboné novellas/novels by Michael Moorcock. His takes on ideas like multiverses and dreams and how these could interact inspired me in much the same way, though from a more positive angle this time around. I started thinking about the idea of dreams as their own world. How would such a thing function? How would intelligent creatures interact with them? How would animals, who dream more simply, interact with these spaces? Would there be denizens of these "dream realms," and how might they recognize anomalies in a realm shaped by the subconsciouses of other beings? What about nightmares, what sort of adverse affects might they have? And, perhaps most importantly, what if someone found a way to twist the rules of these realms to their own ends?