Wong Kar Wai - In the Mood for Love & 2046

or, reckless romanticism and the buried heart blooming

A bit of housekeeping here first.

This essay really got out of hand, in terms of length, and so the only way for you to read all of it is to click over to the website. It’ll take about an hour.

Sorry about that.

But before we hop into it, I have a few things to point you towards and one big thank you.

First, my books are included in this massive sale on Reddit. There are hundreds of other books available for free or for $0.99 per book. The sale ends today, so hop over and spend some of that Christmas money. This is also for charity, after all.

Most importantly, thank you all so much for sticking with me. The fact that I have about ten times as many subscribers now as I did when the year started is astounding.

As a thank you, I’m giving away two of my out of print novels right here. I’m re-releasing them in January and February with some rewrites and several new additions, but you can read the original ebooks now for free.

Noir: A Love Story

Ash Cinema

Thank you all so much. And my final thank you is leaving this un-paywalled, despite everyone who knows about it recommending that I leave it only for those paying for a subscription.

This essay is, honestly, just a bit shorter than my novel Howl, so I understand the impulse most would have to charge for it.

Now, onto this very long essay about my favorite movies.

Catch up:

你好

Whenever I hear someone mention that Die Hard is a Christmas movie, I know an angel loses its wings and because this has become the most common statement from men between the ages of 35 and 50, we’re nearly out of angels.

And so I find it fitting that it took me so long to finally write about my favorite double feature in cinematic history. Because Wong Kar Wai’s 2046 is the most Christmas Christmas movie that doesn’t include or mention Santa Claus. And it gives every angel back its wings.

But before we get there, I need to tell you about the Hells Angels.

so long, childhood: part one

My dream job growing up was to work at Blockbuster. To be surrounded by movies. To live inside that chapel of cinema.

When I was seventeen or eighteen, it did become my job. It was all right. Like any job where you wear a nametag, it was full of hilarity, humiliation, and horror. But looking back at it half my life later, I think it’s still my dream job.

If I had to spend 40 hours of my week standing in a Blockbuster, I don’t think I’d mind so much. I mean, it could be worse. I could be doing whatever my real job is for 40 hours a week.

Of course, all good things are dead and so now we just have our little screens that stream everything and we waste our lives staring at lit glass.

It was walking through Blockbuster in probably 2003 or 2004 that I first stumbled across so many movies that would make me who I now still am. From Andrei Zvyagintsev’s The Return to Pen Ek Ratanaruang’s Last Life in the Universe to Park Chan Wook’s Sympathy for Mr Revenge to Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Bright Future and, of course, to Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love, which is the reason we’re all here.

The reason I’m still here.

When I close my eyes, I still see those corridors made of displays packed with empty DVD cases in that popcorn stinking cathedral to celluloid dreams. I had already been through them all. Had a membership to Blockbuster that I used almost all the time, renting everything I could from the decades of history hidden away behind those ugly Blockbuster logos.

The outer wall was lined with new releases. These I mostly ignored. I had probably seen them in theatre anyway. But after scouring most aisles over the months and years, I found myself always returning to the foreign language section.

I felt eyes I didn’t know I had opening up. Felt my whole life changing with every new movie from Italy or Japan or Russia or Germany but especially from China.

Give me just a lifetime of Zhang Yimou or Chen Kaige.

Let it soak into me. Smother me.

Let it define the shape of my heart and the rhythm of my heart.

My jaw unhinged. Teeth retracting to make even more space. And I gorged. Spent the paychecks I made serving icecream for $5.15 (plus tips (as the kids say, lol)) for rentals that cost $5 per movie.

And then, finally, I found my way to that little island off China’s coast: Hong Kong.

I have, over the course of this series of essays, tried to explain myself to you probably more than I’ve tried to explain the movies I’m discussing.

Perhaps this is a failure. But I cannot think of these movies without myself.

Or, probably the proper way to say this is that I cannot think of myself without thinking of these movies.

And so they all come as one. All together.

And it is a fear in me, I think, that keeps me from separating the two. Because, in theory, I could—and maybe should—discuss the films without myself. Should talk about technique and narrative and acting and camera angles, but I’m instead falling into the angles of my life, the techniques that saved me, the narratives that brought me from despair, or perhaps only through it.

As I said in my review of Happy Together:

Had I had the confidence in you—which is to say the confidence in myself—to understand what this collage would have meant, I would have let the words of others that have meant so much to me speak for this movie, speak for me, tell you the story of two bodies sharing the same heartbeat, the same breath, and how that sharing nearly killed them.

How death is not the end.

How healing happens, at least for the one that remains reaching back for the one now gone to time, to memory, to the mists, suspended in bliss.

Rather than use the art I love to describe a different work of art I love, I am choosing the opposite approach here. For better or worse, all these words will be my own.

And so I must talk about Blockbuster too, and to talk about Blockbuster, I must speak of a man named Will Wilhelmi. He was, I believe, in his 60s or 70s with white hair down his back and a white beard he could have tucked into his belt had he ever worn one.

Blockbuster once had something called the Movie Pass, which allowed you unlimited rentals for a monthly fee, but you could only have one or two movies checked out at a time, depending on your plan. Will had the two movie option and he came in literally every single day.

Sometimes twice.

Almost without fail, he rented the most terrible looking horror movies you can imagine. Things with Cheech Marin on the cover with a grisly gingerbread man. Luckily for him, there was an inexhaustible number of movies like this produced every year. I’ve never seen any of them but I know they’re the worst things made in Hollywood and I also know that they used to make a lot of money.

Like, a stupid amount of money.

All of it on DVD rentals and sales.

Streaming killed this, of course, and now terrible horror movies have to have A24 on the cover or people won’t see them (more on this when I talk about The Green Knight).

Anyway, I’d been seeing him come in every day for the winter when I finally just asked him about himself.

“Oh, I just smoke grass and watch movies.”

Thus and so, a friendship was born.

I don’t know that this sort of thing happens anymore. I don’t know how often eighteen year old depressives get to meet joyful septuagenarians out in the wilds, unmediated by technology, and shoved together purely because so much of life used to force us to leave our homes and go be a human outside, rubbing shoulders and smelling other humans.

I started working the day shift because no one else wanted to because they thought it was boring. It was. I loved it. I spent 8 hours doing not a single thing.

That’s the real dream, babies.

Will used to come in most mornings because if you’re gonna just get high and watch terrible movies, you may as well start early. We got to talking, not only about movies, but about a lot else.

I was reading and rereading Charles Bukowski because it was 2005 and I was eighteen and we talked about him. Bukowski, but also John Fante and Hunter S Thompson. He gave me his old, beaten up copy of Hell’s Angels and told me that he used to ride with them a bit.

“You were a Hells Angels?”

He smiled and said, Not really. He told me that being a biker just meant you sometimes crossed paths with them, went the same direction for a while, maybe landed in the same bar, but he also told me how he was scared shitless anytime they were around and tried his best to say nothing at all, unless asked, and then it was best to just nod along and agree.

He lent me a VHS copy of the movie Charles Bukowski wrote called Barfly and asked me to give it back when I was done because that was something he couldn’t easily replace.

We talked about that, too.

Even when the store was busy, if I saw Will come in, I’d grab a stack of DVDs and tell my coworkers that I was gonna restock, and then I’d spend half an hour walking through the store with him, talking about movies and books and the terrible, very stupid things I was doing and that he did thirty or forty or fifty years ago.

When I went to college, my manager pulled me aside and told me he’d promote me to Assistant Manager if I stayed on.

Netflix was already a household name. They had just begun their streaming service.

Imagine seeing a tidal wave coming and trying to sell houses.

This was a man who I had told six months previous that Blockbusters had, at most, five years before Netflix put them out of business. As it turns out, I was both too optimistic and pessimistic.

This wasn’t really a choice and I tried to not laugh when he asked, but what I did think about was how I’d probably never see Will again.

And so I made a compromise with my manager and worked on the weekends.

Eventually I did say goodbye to Will for the last time.

He wished me well.

I don’t know what our friendship meant to him, or if he even thought of me as anything but some kid who worked at the store he went to every day.

But it’s been literally half my life since then and I still think about Will probably once a week.

Why are you telling me this?

In the past, when someone had to share a secret they could never speak of, they’d climb a mountain and carve a hole in a tree. They’d whisper the secret into the hole, and then fill it with mud.

In the Mood for Love

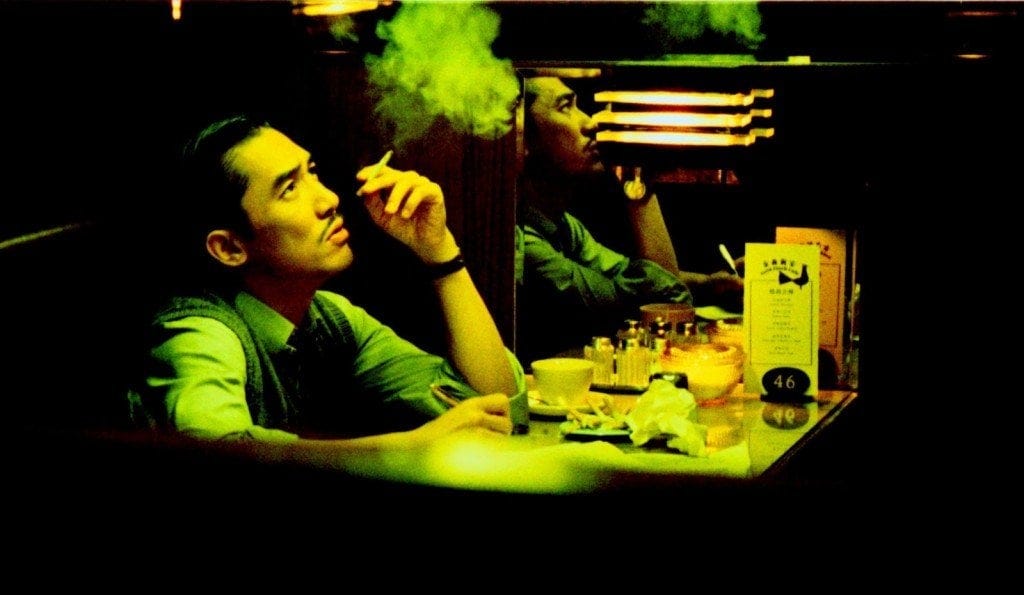

Days of Being Wild ended with Tony Leung getting ready in a darkened room, smoking a cigarette. This man, Chow Mo-wan, is one of the protagonists of In the Mood for Love.

On the same day that Su Li-zhen from Days of Being Wild, now middle-aged, now Mrs Chan, rents out a room for her and her husband, Chow rents a room in an adjacent apartment for him and his wife. They also happen to move in on the same day, and the movers keep accidentally delivering their belongings to the other one.

In this way, they meet. Their lives already meshing together, their belongings swapping, and their spouses curiously absent.

All four of them work long hours. Li-zhen manages her boss’s calendar, including his affair, making sure that his wife and mistress never run into one another. She coordinates the gifts her boss buys for both, the restaurant reservations for who and when.

Chow works as a journalist but he wants to write martial arts serials.

Chow and Li-zhen keep running into one another, passing each other in the street, in the halls, at the communal phone.

It’s 1962 in British Hong Kong. People are packed together. Even without ever stating anything about the political or cultural climate, we understand that everyone works long hours, crammed together. Everyone survives and lives on a complex system of relationships, friendships, and favors.

Through all these many chance meetings, their spouses are always elsewhere. Often abroad. Usually working late. We never see their faces, but we sometimes hear them on the phone, see their backs in a crowded room or between walls, obscured by the geometries of these tiny Hong Kong apartments.

It’s narrative through implication. Half caught phrases and brief encounters, but we come to learn that Chow’s wife is having an affair with Li-zhen’s husband. And both Chow and Li-zhen also learn this, but they pretend not to notice.

Not to know.

They say nothing of it to each other or to their spouses, even when they basically have the proof.

They meet at a diner, seemingly just because they’re neighbors. Chow invites Li-zhen and over the course of their very brief opening conversation, they come to know that both of them know the truth.

Perhaps arranging the affairs of her boss has given her a keener eye for this sort of thing. Perhaps it’s also taught her how commonplace this is and the value of discretion, the way gifts to a mistress and a wife can be identical.

It’s not like either of them would know. And by the time they find out, well, quite a lot has gone wrong by then anyway.

Chow asks Li-zhen about her purse. He tells her that his wife might like the same one.

Li-zhen says, “Maybe she wouldn’t want one just exactly the same.”

“You’re right,” Chow says. “I didn’t think of that. A woman would mind.”

“Yes, especially since we’re neighbors.”

She asks him about his tie.

In both cases, the purse and tie are from abroad.

She tells him that her husband has one just like it. He tells her that his wife has the exact same purse she has. She tells him she knows.

They cannot speak it aloud but they both know.

This scene is so simple. So subtle. And it is, in many ways, the technique of the entire movie.

Implication. Insinuation.

And silence.

They can never say it plainly. Never say to one another, Your wife is fucking my husband.

They wonder how it began and they roleplay as their spouses. Chow as Mr Chan and Li-zhen as Mrs Chow.

But Li-zhen cannot pretend.

It is too painful.

Yet she cannot stop.

As weeks and months go by, they continue meeting with one another, roleplaying their spouses’ infidelity, yet they never take that next step. By inhabiting these other people, they try to understand them. To learn how a relationship can grow, can cause them to become unfaithful, to betray them.

But we see.

We see how they need one another. How they cling to one another. How they begin to fall in love in their spouses’ absence.

They miss each other when they’re not around. Li-zhen even makes Chow the soup he’s craving when he’s in bed, ill. When he thanks her later, she demurs, acts as if she was making it anyway, had extra.

But we saw how she went out to get the ingredients, how she prepared more than she could possibly eat specifically to share with him, though she lies to the other people in her shared apartment.

They cannot speak it.

And so they behave. They act.

They do.

Blaise Pascal, a 17th century philosopher, created an argument that he presented as a wager.

If you do not believe that god is real but you’re wrong, you face eternal damnation. If you’re correct, you lose nothing by choosing to believe that god is real.

In his argument, the way to gamble is to begin behaving as if you believe in god, even if you don’t. Go to church. Follow the sacraments. Say the prayers. Eventually, this playacting will become real for you and you will, slowly but surely, begin to believe.

It’s better to gamble on god’s existence because of the harsh punishment for losing the bet.

We see Li-zhen and Chow at first only behaving as their spouses, but slowly, surely, they become like them.

Excepting that final step.

They cannot sleep with one another.

Chow wants to. Li-zhen may want to as well.

And it is Chow who cannot fake it any longer. We see how he loves her. When he asks her to write his martial arts serial with him, it is in place of a sexual relationship. He rents a room where he works, where she meets him.

Room 2046. A number blazing with meaning for Wong Kar Wai—we’ll get there.

At their apartments, the paper-thin walls, the constant chatter, the people always everywhere, the nosiness, the gossiping—they’re afraid to be seen and so they take their symbolic infidelity elsewhere.

To room 2046.

Eventually, Li-zhen avoids him and it breaks his heart. It breaks her own.

“You won’t leave your husband so I’d rather go away.”

“I didn’t think you’d fall in love with me,” she says.

“I didn’t either.”

Are they still rehearsing? Are they playacting?

It’s real, of course. We know it’s real. But they also lean on the artifice. They hide their emotions behind the play.

“Will you do me one favor?”

“What?”

“I want to be prepared.”

They rehearse their goodbye, knowing it’s not a rehearsal. Knowing that this playacting has stopped.

When he reaches out for what seems the final time, she refuses his grip, and then he leaves. We watch him fade into the background, into the rain, for it is always raining, and we watch Li-zhen collapse.

Chow runs back to her, holds her, and she sobs while he tries to comfort her, tell her that it’s not real, that it won’t be so bad.

But he does leave. And he asks her to leave with him. To meet him at room 2046 before he goes to Singapore.

She can’t. She won’t.

Then she does.

She runs to him.

But he’s already gone.

A year later in Singapore, he tells his friend how long ago, when a person had a secret, they would go atop a mountain, make a hollow in a tree, and whisper it into the hollow and cover it with mud, sealing the secret away.

Li-zhen finds his apartment in Singapore but he’s not there. She calls him at work and when he answers his phone, she cannot speak. Only when she’s gone does he realize that she was there.

Three years later, Li-zhen ends up buying the apartment she once lived in. Sometime later, Chow returns there as well, but finds his old apartment is owned by someone new. He asks about the owners next door and learns that a woman and her son now own it.

Never once does he think that woman might be Li-zhen.

During the Vietnam War, Chow goes to Angkor Wat and whispers something into a hollow in a wall and plugs it with mud.

The final thing we see is that circular hole.

a silence, a whisper, a hollow

When my wife and I began dating, I shoved all my favorite movies at her. I didn’t have the vocabulary of love without the artifice of cinema, and so I believed I could explain myself to her, reveal who I was, by showing her what I loved, what meant so much to me, what had shaped me.

Patient and loving, she sat through most of them.

But this one absolutely baffled her. She didn’t understand what happened. What people were doing or why. At the time, it was simply too much for me to respond to, and so, in a way, that synopsis above is for her, ten years ago, on that night when my heart broke a little bit because a movie that meant too much to me, a movie I had been watching several times a year for seven years, went right by her like the wind, leaving not even the faintest impression.

There is no hand holding in In the Mood for Love.

It’s all gesture.

It’s all about the things people don’t say.

a silence

There’s a moment early on when Chow speaks with his wife on the phone. He offers to pick her up from work so they can get dinner. She tells him not to bother because she’ll be working late anyway.

Well, fool that he is, he goes anyway. He stops by to pick her up only to discover she left early. Rather than show to the receptionist that his wife has lied to him, he smiles and says that she’s always forgetting to tell him when she’s leaving work.

This is the moment he discovers his wife is, truly, cheating on him.

He meets it with a smile rather than anger.

This moment is, in a way, the whole of the emotional resonance of the movie.

If you see this scene and don’t feel the despair in it, the horror, the absolutely mangled corpse of his heart, you’d be forgiven. After all, Chow behaves as if this is an honest mistake.

But it’s the end of his marriage.

The end of the life he believed he had.

Li-zhen and Chow are only able to speak, to say what they mean, when they are pretending to be one another’s spouse. Chow can speak freely to Li-zhen when he is her husband and she is his wife, Mrs Chow. Li-zhen, wearing the guise of Mrs Chow, eating the food she eats, saying the things she’d say—that is the only time she can show Chow how much he means to her.

How living without him will break her.

And she does fall apart when even the thought of him leaving without her is cast through the air.

And it is never entirely clear if Chow is saying goodbye as Chow or as Mr Chan, or even if Li-zhen is taking this as Li-zhen or if she’s taking it as Mrs Chow.

I see how you could be confused.

The only time I’m honest with myself is when I’m wearing a mask looking at you, your face covered in a different mask.

a brief aside about AOL Instant Messenger and 2004

I could speak to you.

You could speak to me.

I didn’t even know you. You were the friend of my friend and one day while at his computer, while he was off doing whatever we were always doing when we were sixteen, you messaged him and I responded, just to mess with him, to mess with you.

I didn’t have access to a computer because we didn’t have money for that sort of thing. I only used my dad’s after he went to bed or when he was done with work for the day. My friend Eric made me a screenname one day because he wanted me to join the 21st century and so I became wetheadeddy.

Your screenname changed often. Everyone’s did. But mine was always wetheadeddy.

I came to know so many of you. And while I talked with people I knew well, that I saw all the time, that I hungout with, I also came to know some of you—all of you women—the way I knew no one else

It was, in fact, because I didn’t know you that I could reveal myself to you.

When I told you who I was, without artifice, without my body, without my voice, you took me at my word for there was nothing else to go by.

I was only my words.

You told me who you were and together, I went on a journey with each of you. I came to know so much about you, but especially the interior of you. We spent millions of words howling into the digital abyss, filling that digital urn with our digital ash, the linguistic detritus of our broken teenage hearts,

Every day, my heart was breaking. But I went to school and smiled and laughed and was the me people believed in, the one I wanted them to see. I wore my mask and I wore it well, but it began to splinter me to pieces and I began shattering all the time, everywhere, and I stopped sleeping and I kept drinking, and I longed for death, prayed for it, and I unloaded all this pain into you.

Into all of you.

And what did I give back?

Well, I suppose I swallowed all of your pain too.

We became snakes eating our own tails in front of one another.

And all of it happened primarily online.

I remember, even, the first time I heard your voice.

I had never seen you, even after weeks of talking online.

To me, you were only words on my screen.

And then, one evening, without warning, your voice was in my ear.

And then I met you.

And we spent months talking on the phone for literal hours.

And we became a new kind of person together, privately, for we were rarely with your friends or with mine. Instead, we were sort of our own private secret, belonging to one another.

Eventually, this led me to leave the US twice. Both times to escape my own heartbreak. To escape you and the shadow you cast over my life.

And all along, I was watching In the Mood for Love.

a whisper

Wong Kar Wai’s occasionally dabbled in the wide open. Happy Together takes place in Argentina, with vast vistas, with that unforgettable waterfall. Ashes of Time has the desert stretching endlessly.

The camera always distorts these spaces, excepting the waterfall. As if there’s an anxiety about the open air, the open streets, the wide wild landscape of those other places.

Even in China, with all that space, Wong Kar Wai chose to film most of his wuxia epic in crowded, cramped, dark rooms. Even in Argentina, much of the movie takes place in that absurdly small apartment.

The visual flair of Chungking Express lived because of the crowded streets and hallways of Hong Kong. He showed the liveliness of his city. How evocative and wild the enclosed life could be.

In the Mood for Love stuns us with the beauty of this cramped and small world. We are always looking around corners, between cupboards, down hallways. There’s a sense—and a reality—that the camera and crew barely fit in the scene and yet the scene happens, life goes on, and the cameras simply try to capture what footage they can.

Rather than have this break the film, it becomes the visual language of the movie. This world of thin walls, of nosy, noisy neighbors, of gossip, of insinuation and assumption—we, the audience, become voyeurs on their relationship, just like their other neighbors, their landlady and landlord. They, too, only catch glimpses of them, snippets of conversation overheard through the door or wall, around the corner.

Even when we’re outside, it’s raining, as if nature itself holds in the film. And though In the Mood for Love has a number of characters, it’s really the story of Chow and Li-zhen. Everyone else is just set dressing.

And the set dressing is naturalistic in all cases, which makes Cheung’s dresses pop out all the more. It is one of the most distinctive and commented upon aspects of the movie, yet I find myself always asking:

Who does Li-zhen dress up for?

The dresses of In the Mood for Love are, for a certain person, the most striking part of the movie. She wears these gorgeous and intricate qipaos.

Perhaps it’s only to reveal and accentuate Maggie Cheung as one of the most beautiful women of the era. Perhaps there’s so much more.

When I think of In the Mood for Love, I do think of the dresses and the wallpapers, the streetwalls covered in papers, in language. I think of rain, for it’s almost always raining in Wong Kar Wai’s Hong Kong in 1962.

Despite her extravagant qipaos, we only ever see her in the rainy streets, the cramped office, or her even more cramped apartment building. If they are of such modest means to need to rent a single room in an apartment, where do these dresses come from?

Her husband goes abroad and buys her gifts, and yet he is never there.

He is never there.

Gone.

Absent.

Notice me.

See me.

Come to me.

Run to me.

Who am I to you?

What am I?

Did you never love?

Did you ever love?

Instead, he noticed me. He saw me.

He loves me. He wants me. He spends all day thinking about me. Dreaming about me. He has forgotten his wife. She’s gone from his thoughts, from his world, even as she spends all her time with you.

And yet you still cannot see me.

He saw her and let her go, but he will not let me go.

He loves me.

He needs me.

He wants me.

He begged me to come with him. To leave you.

Look at me.

See me.

Please.

a hollow

Before I could whisper my secrets to you over the internet or over the phone or into your ear at 3am on swingsets in parks with 40s in our laps, I whispered my pain into my dog, into my window when I was up all night staring at the moon, standing on my roof, breathing smoke, my dad’s cigarette pack in my pocket.

Wong Kar Wai has always used music in interesting ways, but this is where I find it most striking. While there are several pieces of music for In the Mood for Love, most of the music used in the was not made for the movie, including Yumeji’s Theme by Shigeru Umebayashi, which has come to be defined by its inclusion, by the way it comes to dominate the soundscape of Chow and Li-zhen’s hearts.

But the song was originally made for a different movie called, appropriately, Yumeji by Seijun Suzuki.

And yet I find the plucking arrangement so perfect. There’s a lightness to the way those violins are plucked, and so when the other violin cuts through it imbued with feeling and melancholia, the dual natures of the film tickle their way through our skin, running along those tiny hairs covering our body, working galvanically upon us, writing inside us the emotions that Li-zhen and Chow cannot say aloud.

So often the music is used when Li-zhen is in motion, her qipao catching our eye as she strides confidently through the rainy Hong Kong streets of 1962, of now, of forever, the Hong Kong of 1962 that is the geography and topography of our hearts.

Michael Gelasso’s ITMFL, which was made for the movie, mirrors Yumeji’s theme with its pluckiness and the flute slicing through it. There’s a slightly more sorrowful sound to the plucking yet the flute feels livelier, as if Chow is bursting with even more life.

And we see that in his character. The way he smiles, is self-effacing, holds onto ambition even as he toils away doing work he cares little for. When his wife begins her affair, it’s Chow who’s more willing to leave her, to move past her, and, in the end, it is only he who leaves his spouse.

Or so it seems.

Gelasso’s Angkor Wat Theme doesn’t arrive until the very end of the movie, and yet it mirrors and distorts both Yumeji’s theme and ITMFL. There is still that plucking, but it’s now on the string of a cello. A dour, tempered plucking that no longer sounds or feels full of life and verve.

And then when the other cello comes in, sawing its baleful radiance through us, we are devastated. Even if you listen to it now, eyes closed, not knowing or watching the final scene of In the Mood for Love, you will still hold a heart fragmenting and falling apart.

My breath leaves me. My lungs empty yet my mouth hangs open.

Agape. Agapē.

Divine, unconditional love.

Shattering.

2046

From the very first moment of 2046, you know this is going to be a very different experience. Where Yumeji’s Theme and the Angkor Wat Theme approaches with a slightness, a minimalistic touch, the 2046 Theme by Shigeru Umebayashi overpowers you.

There’s orchestration here, a suite of instruments and musicians working in concert rather than the singular voices of In the Mood for Love.

This song arrives like a train, storming across the landscape, bringing beauty and terror with it. It struck me for the first time like a punch, bowling me over, especially after the gentle caress of In the Mood for Love, which crosses you like a feather carried by the wind, though it brings an emotional freight train with it.

And the style feels dramatically different right from the opening scene. We’re thrown into a science fiction setting of the near future, of the year 2046 as imagined by Chow after the events of In the Mood for Love.

2046 is full of women and Chow bounces between them, treating some well and some terribly. Rather than force the viewer to make sense of the insinuated and implied romance, Chow speaks directly to us. A voice over draping the entire movie in his personality, in his evocations, his incantations.

And while In the Mood for Love stayed focused on two people, excising nearly everyone else, 2046 sprawls, tendriling out to pull in more and more. Rather than the linearity of In the Mood for Love, 2046 also plays with the clock, with the calendar, racing forward and doubling back, sometimes retreating years into the past before leaping years forward.

We’ve seen how Wong Kar Wai does this sort of doubling before, with Chungking Express and Fallen Angels. A movie for day and one for night.

In the Mood for Love is for the heart, the soul of us.

2046 is for our bodies.

A world connected by trains, where people are served by androids while they seek 2046, a place where time stands still.

Where there is no loss or sadness.

A place where no one leaves.

The tunnel of the train, a vast hole.

We have seen this before.

We have been here before.

Do you remember?

Can you remember?

There are many signals right at the opening of 2046 that this will be unlike any sequel you may have expected. It is, in many ways, the opposite side to In the Mood for Love.

There’s a lushness to the cinematography, to the action, to the acting. Even the voice over marks this as a very different experience. Because Tony Leung, right away, begins grounding you in the world. Both the one he’s writing and imagining, in the 2046 storyline, but also in his present, where he meets Lulu.

Do you remember?

Can you remember so long ago?

Chow returns to Hong Kong after years in Singapore and has become, surprisingly, quite the lady’s man. I mean, this isn’t really surprising if you have eyes to see Tony Leung wearing the hell out of his suits, sporting that Clark Gable moustache.

We met Lulu in Days of Being Wild. She fell in love with Leslie Cheung’s Yuddy, the protagonist gunned down at the end of that movie. Sadly, Leslie Cheung was also dead in real life by the time this movie came out.

For those who don’t remember, she went to the Philippines to find Yuddy but arrived after he died.

Lulu and Chow get drunk together and he walks her back home. There are several call backs to Days of Being Wild here, and this is the most direct connection between all three movies.

The bird never landing. The dead boyfriend.

When he brings her to her apartment, he sees the number of the room is 2046. Chow is struck by the number. This number. It has come to mean so much to him, to represent something, some time.

He comes back the next day to return her key and discovers she was stabbed to death by a jealous man from the club she worked at. Chow wants to rent the room but the landlord, upon finding out that he’s a writer, a journalist, wants him to stay there.

A respectable sort, or so he thinks. The kind of client he wants in his home.

But since room 2046 isn’t ready—it becomes clear Lulu was murdered in her room—he tells Chow to take room 2047. Once 2046 is renovated and cleaned, the landlord asks Chow to take the room, but he now prefers 2047 and remains there.

sayonara, childhood: part two

I went to Ireland to escape you. To run from my own pain. My heartbreak. The knowledge that I could not be—

That you could not be—

That we—

A year of reckless romanticism. Of blatant dandyism. I threw my heart into the chests of others. Gave it away for nothing. For an hour. For a minute. For six whole months when she danced in my arms, held my hand, spoke those words I always needed while on one of the ten trains taking us from Paris to Munich, through the rain, through the confusion of a language neither of us spoke or read in a world before smartphones and google maps, where she had a binder for our itinerary and I had nothing but myself, but my fragmented, fragile, fungible heart.

But it was a different night. A different woman, before I met the woman with your name who almost made me forget you, who almost made me believe, who almost saved me, who maybe could have had she not had a boyfriend, had she—

I don’t even remember your name, my love

I didn’t get along with my roommates when I arrived. Probably I’m to blame. Of the 9 of us in our program, I was the only man and so two of the women had to live with me.

I imagine this surprise was not a welcome one, and so we spent much of the year we lived together sort of living around one another. There were the frictions of any roommates, especially those thrown together by circumstance rather than friendship, but we eventually came to a sort of friendship. Or an understanding.

It only took most of the year to get there.

But there was a night somewhere in the middle when I had nothing to do and they had a friend over and so they invited me out with them. Much drinking was involved and their friend was pretty and who was I to say no to a pretty face while I was already halfway to drunk.

We talked literature and my own fumbling attempts at it. The places I was getting published already. We went to a bar that had a sort of open mic night where people read poetry and other such things.

I remember none of it except that I laughed a lot and that pretty girl with curly hair and brown eyes kept looking at me, kept sitting by me, kept leaning into me when we stood anywhere, and when we wandered back to our apartment, still talking books, she stumbled into me, held onto me.

I have never liked the way I look. Never once in my life did I believe myself beautiful, even when women showed me in dozens of ways that it didn’t matter what I believed about myself, my looks, but because of this, I never really knew what to do with the affection and obvious attraction of women.

And suddenly she seemed so much drunker than I expected.

Went from laughing with her to helping her along, holding her up.

When we got back to our apartment, we didn’t have a room for her.

All three of us had single beds. Their room had two beds but so did mine. One of my beds, for this reason, went unused. But because it was the bed available, we deposited her there.

I sat with my roommates for a while and we laughed, had another drink. We had had a fun night. Maybe our first as roommates.

I cherished that, even though I didn’t particularly like them. They didn’t particularly like me either, but I think they, too, had a certain affection for me that night, and most nights after.

As the night tumbled into the darkest hours, I asked one of them to check on her so I could go to sleep. I don’t remember what the outcome of this was except that I went into my room where she slept and lay down on the other bed.

I can’t even remember your name, my love

I stared at the ceiling, out the window. The darkness all around but the hum and thrum of fun and drink still swelling within me.

And then I heard her voice.

Come here, she said. I rolled out of bed and crouched down and said, What?

She said, No, come here.

I told her the bed was too small and she was drunk.

She told me to push the other bed closer. She told me she didn’t want to sleep alone.

Who was I to argue.

I pushed the other bed next to the one she slept in, which was the one I had slept in every night since living there. I’d never once slept in the bed I had been lying in. Mostly, it had been a place for me to throw my books, my clothes.

I got under my blanket and got into bed and she scooted closer to me, beneath her own blanket.

We talked for hours. We talked about books and music and movies. She told me about her dad. About her childhood. I listened and told her about myself, but never the real me. Never the pained me.

Never did I mention you.

I didn’t tell her the truth, but I enjoyed talking to her.

She gave me signals. Perhaps every single one a woman might know.

I kissed her. She kissed me. She pulled me onto her. She spoke such words to me.

I pulled away, moved the hair from her face, and told her she was beautiful. I kissed her again and rolled away.

We spoke more. We talked until the sky blushed with the faintest touch of light.

She pulled me to her again and I kissed her once more and she kissed me and I told her she was drunk and she told me she wasn’t and I told her that I didn’t believe her, that I didn’t know her, and I kissed her again and rolled away.

I woke up an hour later when she rolled out of my bed and put on her pants that I didn’t know she had taken off.

When she left, I didn’t say goodbye and she didn’t look back at me but I felt a kind of lightness. A kind of beauty.

I felt happy. Felt alive.

Felt beautiful and free.

I had wanted to. Maybe should have.

It didn’t entirely occur to me at the time that, perhaps, she had not been drunk at all but had simply wanted me to find her in my bed, to join her in that bed, to do what people do when they temporarily fall in love.

And I did love her for that night. For the hours she was with me. For the hours I knew her.

Maybe had I been a different boy. One less heartbroken. One who saw himself the way others saw him. Maybe I would have understood that she wanted me. That she wanted me to be there in bed with her.

She was cold to me the next time we spoke and I understood that she took my rejection for, well, rejection.

But, that morning, I felt only lightness. Only beauty.

I cherished that night then and I cherish it even still, all these years later, though I remember nothing that was said or even her name or face. Only that sensation of peace, of love, of gentle light.

I smiled and, for a time, forgot about my hurts and the pain I carried around with me.

I fell in love with a beautiful stranger and she loved me, at least for a moment, an hour, a night.

I can’t even remember your name, my love

And this cycle repeated in my life. I met strangers and loved them. Loved them deeply for a time. For an hour. For a minute. For the whole night through. For the length of a dance, the instant of touch, and then they were gone.

I was twenty three and she was thirty and when she found out she stopped talking to me. But first we had that night where we moved as one, where she told me her name and I forgot and kept forgetting because the night was a blur and I was far away, inside myself, but she found my apartment phone number, which I didn’t even know, and she called me to meet again.

And she went cold when she found out I was so young.

A month later I met my friend Andrew and the two of us tore through Korea in a friendship I cherished but that couldn’t last past that peninsula, past the thousand miles of distance between us for the rest of our lives.

But I went to Busan with him and some others and we spent the day the way we so often did. Which is to say we drank too much and made fools of ourselves and in the evening, at that bar, he bought two bottles of Jägermeister for himself and then I saw her walk through the door of that stupid bar where Andrew passed out and I had to sit down.

After enough encouragement from one of Andrew’s bottles of Jägermeister, I went to her and made a fool of myself, but she was kind about it. She danced with me. She spoke to me.

She stunned me with the way she moved, the way she looked, the way she both pushed me away and pulled me close.

She told me she and her friends were leaving and so I went to my friends, told them I was leaving too. They asked me if I knew the way back to the hotel and I lied, Yeah, sure.

At the club, the lights streaked, the bass pounded, the sweat, the taste of sweltering air, of alcohol. I asked her name and she whispered in my ear, No. And that swelled inside me, nearly buckled my knees, and I thought of nothing again but her, but touch, but lips, but hips, and when the drink and touch got too much, I had to sit down.

Foolish. Failing. Feeling the world slip away.

But she came to me there as I sat and sat with me and waited out the night with me and when we left the club as daylight broke over the coast she held my hand and led me through Busan telling me of herself, but only just enough to make me always want more.

I loved her so much that night, I would have done anything she asked, anything she told me.

Kill me, I begged inside.

I’ll love you for all eternity if you kill me tonight.

She spoke Korean fluently and I wanted to know her story, what brought her to Korea, who she was, truly, but mostly I wanted to know Why me?

Of all the men in that bar, in that club, why she chose me.

And, I suppose, the answer, both now and then, is that I chose her to throw my heart into. But it’s also true that she could have ignored me, sent me away.

And maybe she was never as pretty as I believed, as irresistible as I saw, but she meant everything to me that night that I walked with her back to her hotel. When we got there, she told me again, No, and I loved her more for that, for kissing me goodbye there in the street.

I asked her name again and she looked at the sky and told me that it didn’t matter.

And I walked away, back into the early morning of Busan, ecstatic and light, like a burden had been lifted from me, for love is that way. Love, even the temporary kind, can rebuild us. Can give us life. Can make it worth living.

Perfection is temporary.

Evanescent.

A transient experience built from love, from beauty, and, to me, then, from its passing.

We can only expect a moment of perfection. And I clung to that idea, to that dream. I collected those moments of perfection like crystals, like talisman, like dreams. My memory comprised of all these jewels of perfection, scattered like stars across a blackened night breathing smoke into the watchful moon where I longed and hoped and believed.

A month later, she added me on facebook. I messaged her right away and we talked a bit, though she didn’t tell me how she found me. She told me to come back to Busan to see her and I told her I would. I looked up bus tickets that same day.

I never saw her again.

We still follow one another on instagram though.

If you’re reading this now, Hey, how ya doing?

Also, sorry.

It was only after walking away from her that night into the Busan bursting with light that I realized I had no fucking idea where my hotel was.

Traces of Tears

Jie-wen, the landlord’s daughter, begins living in room 2046. He hears her practicing Japanese through the walls because she fell in love with a Japanese man. Her father won’t allow her to be with a Japanese man because of the horrors of Japanese imperialism inflicted upon Hong Kong.

Many movies have depicted this, from Ip-Man to Fist of Legend, and on and on.

If you’d like to know more about Japanese Imperialism, there are a thousand books about it, but The Rape of Nanking is worth checking out. If the title doesn’t give it away, just know that it’s real bad.

Chow observes this heartbreak but mostly ignores it while he carries on with his own life as a playboy about town. The Hong Kong riots create difficulties for many and Chow’s lifestyle begins to leave him in dire need of money. And so he begins writing a surreal science fiction romance called 2046, inspired, in part, by Jie-wen, but also everything happening around him and all the people surrounding his life in that moment.

The protagonist, Tak, is a Japanese man, for example. The only one to return from 2046. A man who falls in love with one of the androids aboard the train.

This movie began with scenes from that work.

Jie-wen runs away from her father’s house.

a brief aside about politics

Hong Kong was part of Great Britain from 1841 to 1997, excepting when Japan occupied the island from 1941 until 1945. As stated above, these brief four years were brutal and full of crimes against humanity, though, curiously, few Japanese officials or generals were tried and many of them would go onto have successful political careers in Japan. One of the main reasons for this was because the US did the political calculus after the Chinese Communist Revolution. They needed a strategic ally to combat the spread of communism.

Or so the saying goes.

Thus and so, Japan whitewashed its own crimes, denying most of them, writing their textbooks in such a way that generations of Japanese people learned that they were the victims of Western aggression rather than some of the most heinously brutal imperialists in history.

Which is really saying something, considering they were contemporaneous with the Nazis and allied with the Nazis (curiously, it was a Nazi official in Nanking who saved much of the Chinese population from rape, torture, and murder during Japanese occupation—if you want to hear more, you really should read The Rape of Nanking).

And so, if you know any history, it’s not surprising that a Hong Konger in the mid-60s would be extremely anti-Japanese.

It’s possible, even, that his mother was a comfort woman.

For those who don’t know, comfort women were women that the Japanese army forced into sexual slavery during occupation.

Whatever the case may be, Jie-wen’s father hates the Japanese.

But after WWII, Britain took Hong Kong back.

This occupation by Britain made Hong Kong immune and completely separate from China during most of the 20th Century. This means there was no Communist revolution in Hong Kong or Cultural Revolution. In many ways, Hong Kong became more western, more international and cosmopolitan than the rest of China.

However, with the signing of the Sino-British Declaration in 1984, Great Britain agreed to transfer Hong Kong back to China. Hong Kong would become a special administrative region and remain separate from the rest of China for 50 years.

Hong Kong would then integrate into China by 2047.

Or so the declaration went.

Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together, which takes place in 1996 and 1997, is about the anxieties of this handover. The terror involved.

Wong Kar Wai is a Hong Kong filmmaker. Perhaps the most Hong Kongese filmmaker. The year 2046 took on a special significance for him, for obvious reasons. His distrust and anxiety over Chinese rule has, I think, led to him being unable to successfully bring a project to fruition since The Grandmaster, which came out in 2013.

You may call this a case of blacklisting.

The following year, the Yellow Umbrella Movement began in Hong Kong, which has led to brutal crackdowns by the CCCP. The friction between Hong Kong and mainland China has continued in the ten years since, with China exerting more and more control over Hong Kong.

In 2015, I spoke with a Hong Kongese college student in New York. I asked him about the unrest in Hong Kong and he was a mix of terrified and outraged.

He told me that the way mainland Chinese had flooded into Hong Kong, and especially into the universities, would eradicate Hong Kongese culture. A Cantonese speaker, he said that more and more classes were being taught in Mandarin and fewer and fewer were being taught in Cantonese to accommodate for the mainland Chinese students.

He feared the loss of his language.

The loss of his culture, since there were over a billion more Chinese than Hong Kongese. Just through immigration, there may soon be a time where mainland Chinese outnumber Hong Kongers on Hong Kong.

A fear of immigration is typically coded as rightwing for Americans, but I think it’s worth considering why people in Hong Kong would be reluctant to have their distinct culture be swept away by a nearby culture with 1.4 billion more people.

When I lived in Ireland, some Irish offered a similar reason. The Irish, after 1,000 years of imperialism, had only been a free nation for about 80 years. Most of that time was spent in relative poverty, with the population continuing to dwindle through outward immigration.

Then, the Celtic Tiger roared and this nation of about 4 million people became flooded with immigrants from around the world.

The people I spoke to who expressed this fear—a young, liberal man and woman at Trinity College Dublin—said that Ireland had really only had a generation to be Irish before the rest of the world came to fill their island. They’re still in the process of rebuilding literacy in their indigenous language and now there were people from dozens of countries, speaking dozens of languages, taking residency in Ireland.

Make of that what you will. Perhaps all these people are ethnofascists. Or perhaps post-colonialism is a bit more complicated than Americans would like to believe.

At the same time that I spoke with that Hong Kong student, I began working with a Hong Kong company that has a factory in mainland China. The owner of that company sees the loss of Hong Kong as inevitable and therefore nothing to get upset over.

He said the unrest will die out and, eventually, in a generation, Hong Kongers will be Chinese, just like the rest of China.

I offer these opinions not to try to dodge a question but to frame the debate.

As an outside observer, and a lover of Chinese filmmaking, I can only say that I feel the exertion of the CCCP on Chinese art has been disastrous to some of the most accomplished filmmakers alive. Artist who made beautiful, transgressive films who now make high budget propaganda.

And my favorite filmmaker of all time has made nothing in ten years.

Now, politics are complicated and so I won’t pretend like the loss of beauty and artistry is the same thing as a totalitarian regime crushing dissent and ruling over its citizens, but I don’t think the two are unrelated.

爱

I fell in love with Zhang Ziyi the first time I watched Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon when I was thirteen, and I fell in love with her again when I was fourteen watching Zhang Yimou’s Hero and then again when watching 2046.

To me, this is her career defining role, though probably no one else remembers or feels the same.

When Bai Ling arrives on screen, you’re knocked over by her. Vivacious and haughty and beautiful and teasing—she’s the kind of woman who kills me.

Please, kill me.

I beg you.

She notices Chow first while he’s having loud, aggressive sex on the otherside of her wall after moving into room 2046. She hears every thrust, every gasp, and she beats the wall telling them to stop.

Bai Ling and Chow become friends after she’s stood up by her ex-boyfriend who abandoned her for Singapore on Christmas, after some amount of teasing, of crossing one another in the hallways to their apartment.

She’s a cabaret dancer and a prostitute, but she’s also a woman. A woman who needs a friend. And Chow is that friend, at least for a time. He comforts her but also tries to keep a romantic distance between them.

If you’ve never seen the movie, it really should be stated just how irresistible Tony Leung is. There’s a trope that Asian men can’t be sexy or that no one views them as sexy in the US.

If you’ve ever seen Tony Leung smoke a cigarette, you’d be cured of this opinion. He’s as much Marcello Mastroianni as he is Clark Gable, but there’s a bit of a sinister edge to him in 2046 that gives him this gravity, this ability to pull you in and leave you breathless.

In some ways, this relationship with Bai Ling is a funhouse version of Chow’s relationship with Li-zhen.

Even her dresses remind the viewer of Li-zhen’s.

But where Li-zhen is calm and poised and dignified, Bai Ling is loud and abrasive and coquettish and overflowing with sexuality.

Where they were chaste, their lives enmeshing, always intersecting, Bai Ling and Chow spent a long time avoiding one another, with sex always between them.

But slowly, just as with Li-zhen, their relationship blossoms. Bai Ling grows attached to Chow and maybe even loves him. When they first have sex, she’s so pleased. You can see it in her face, in every movement she makes.

But he gets up and gets dressed and asks how much he owes her.

Her expression fractures for a moment.

For her it was real. There were no masks or games. She wanted him. Maybe needed him. And when he offers her money, reminding her that she is but a whore to him, it takes my breath away.

She says it’s on the house, regaining her composure, but he insists, and so they agree on ten dollars, a laughably low number for her.

But she stuffs it in a box. And when they repeat this over and over, she continues to stuff every ten dollar bill in the same box.

She loves him but he gives her nothing but gentle indifference and sex. And when she wants more, when she demands more, he refuses. She tells him that he can have other women. He doesn’t need to change. But she won’t be the same as them.

She’ll be the first among his women.

Still, he refuses.

“I don’t care if you love me or not. I’ll love you anyway.”

She’s standing there, saying goodbye but asking him to come with her. For them both to escape the life—the lie—they’ve been living.

Come with me.

Be with me.

Love me.

See me.

She hasn’t seen any men since they had sex.

Here, we see the brokenness of Chow. The cold indifference heartbreak has instilled in him.

He cannot love.

His heart belongs to another and she’s gone.

Gone, long ago.

Never to return.

When Chow refuses and rejects Bai Ling, she begins prostituting once more, trying to make him jealous, but it doesn’t work.

In every movement, every action, she wails for him to love her.

But he ignores her.

Eventually, she moves out of 2046.

She runs away from her heartbreak. From his rejection.

And then Jie-wen returns and he repeats another cycle with her.

They begin working on a martial arts serial together.

During this time, her Japanese ex-boyfriend who she had to reject because of her father begins writing her letters. This drives her father crazy once more, and he refuses to give her the letters.

Chow offers to be a go-between.

She has her ex-boyfriend send the letters to Chow. Then he hands them to Jie-wen, who writes him back, and Chow puts the letters in the mail.

Chow describes it as the happiest summer of his life.

They spend their days writing a martial arts serial. She plans her life with her Japanese boyfriend but tells her father that she’s in a relationship with Chow.

Her father—his landlord—is overjoyed.

Another fake relationship. This one chaste, like Li-zhen. They write together, just as he did with Li-zhen. And, once more, he begins falling in love with her but she can only think of her Japanese ex-boyfriend.

She asks him one day if things in life never change.

In response, he begins a sequel to 2046 called 2047.

While Tak, the Japanese protagonist, was originally meant to be modeled after Jie-wen’s ex-boyfriend, he becomes Chow.

In 2047, he’s leaving 2046 because he lost his love there. The train taking him away is full of androids who take care of his every need. Tak falls in love with the one assigned to him. Both this android and Jie-wen are portrayed by Faye Wong, another actress who I could watch forever, who shatter my chest with a certain look they give.

Tak tells her that in older times, when a person had a secret, they would go atop a mountain, make a hollow in a tree, and whisper it into the hollow and cover it with mud.

“I’ll be your tree,” she says. She holds up her hand and forms a circle with her fingers.

He whispers into it.

Leave with me.

They do this together over and over and over.

And Tak is told not to fall in love with them because they degrade, and their reactions slow.

Though he falls in love with the android, she never responds to him.

We see her react to things he said long after he’s gone. As if she simply takes it in but can only respond later. So degraded has she become that her present and his misalign and they can never be together at the same time.

Love and timing.

Out of sync.

Out of tune.

Like a lullaby on a corroded music box.

Over time, Tak realizes that the android did not love him. Never loved him.

The following Christmas, Jie-wen goes away. To Japan. He finds out that she’s getting married from his landlord, her father, who is now overjoyed, despite the fact that her husband to be is Japanese.

As if it never mattered. As if these political differences, as if nations and ethnicities, never meant anything, could never mean anything in the face of love.

Chow helped heal her relationship and she found her love.

Something he could not do all those years ago, at that other apartment, with that other woman who held his heart in his hands.

Li-zhen.

He sent Jie-wen 2047 as a wedding gift but she told him the ending is too sad. He should rewrite it.

He tries.

He tries for many days. For weeks.

He cannot.

He cannot find the words. Cannot find the hope inside himself.

Loss. Absence. He cannot think of Jie-wen without thinking of his happiness, now gone, given to another. Cannot think of her without remembering Li-zhen and the time they spent in 2046 writing a martial arts serial and rehearsing the relationship of their spouses.

These masks. This pretended love. The shared task of making art, bringing them closer than the sex he compulsively had with Bai Ling or any number of other women who fill his nights but go uncommented on in the movie.

There is no happy ending.

He lost it.

A long time ago.

An Image, a haunting

I want to talk about an image from this movie that has been caught inside me for 19 years.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, how many will it take me to explain this?

Perhaps brevity is best.

Haunted.

She haunts me. This look, this image. It is the specter wrapped round a dream of love, of life, of endless sleepless nights when I stared at those Korean mountains, at that Minnesota moon, at those Irish stars. When I inhaled smoke and it plumed out of me, it was this look in those sorrowful eyes that made me shudder.

A beautiful kind of pain.

An addictive kind.

Thus and so, I fell in love with my own heartbreak, my heart aching in a pleasurable sort of pain. A hurt I can still taste, like wine at the edge of spoiling. Terrible, yet I cannot dump it down the drain.

I drink it, loving the burn.

All Memories

Depressed and devastated, lonely and loveless, Chow runs into Bai Ling again. She seems forever trapped in the past and he sees himself in her. And it’s not what he wants. Not who he wants to be anymore.

Later, she calls him to meet her for dinner. Again, she’s depressed and lonely, alone. As a viewer, we cannot help but see why she’s called him. What’s brought her to this state of misery.

Who could she be had he not rejected her?

What would her life be now had he said yes?

It’s a question thrumming in my chest, even now, and I see it so clearly splintering through Bai Ling, causing her to shatter, for her heart and blood to smear across the screen, these moving images trapped in film.

She wants to leave Hong Kong. Needs to.

Singapore. That place of endless promise. A new life. A new place to hope.

She tells herself it’s to start anew, but I feel the way she must run from him. Escaping Hong Kong. Escape him.

But I’ve gone to the otherside of the globe and know, now, then, that you cannot run away from yourself, from your own bleeding heart. Your ghosts and your hauntings, chained to you, ride along inside your chest, like an iron maiden round your heart.

She needs his reference to buy a ticket, but she also asks him for airfare.

He smiles and obliges.

They’re friends, after all.

And him saying this breaks her heart.

It’s almost cruel to hear him say it. To see her begging him this way and for him to reject the love they shared, to tell her that that love was misinterpreted, that they were only ever friends, and she was a whore.

It’s the mirror of those scenes in In the Mood for Love. Bai Ling cannot say what she means, for fear of what he’ll say. And he doesn’t want her to ask, to say it, because he does not want to tell her No.

He says none of that in words, mind. But in reminding her that they’re drinking buddies—I gasp, even still, at the brutality of it.

Before they part, she asks him where he was last Christmas. She looked for him, called him.

And he was in Singapore, trying to find Li-zhen.

A different Li-zhen.

Mirrors and masks and cycles.

2046 is a hall of mirrors and we all stand naked within it.

告别, childhood: part three

When I ran away from my brokenheart and found myself in Ireland with a woman with the exact same name, it felt like fate.

I have never been one for omens and such. But it seemed oddly fitting that these two women should share a name but nothing else.

In Ireland, I found that I could ignore my past, even if I could not outrun it. But I chose to bleed that all away and I told no one there of the pain I once felt at 3am on a swingset trying not to cry because of all the things between us and all that they would never be.

But on mountains wandering Neuschwanstein, I thought maybe the future opened before me because of the woman by my side. She was in love with another, had a boyfriend, but I didn’t mind.

Didn’t care.

I hoped, sadly.

She smiled, happily.

I wore bruises from her smiles, from her looks, from those touches, the way she’d take my hand and drag me to the dancefloor sticky with beer and spit and wine and the air hot and fetid full of sweat and our bodies tightly packed and the slickness of our skin as we shed layers there pressed between all those bodies while she felt me and I felt her and the world dissolved around us and I gave everything I could though I never once spoke those words aloud, not even whispering them at 5am while holding hands in the black Irish nights when I told her the words so close but not fully there, I could die happy right here.

And everyone saw it. What was between us. The love we shared when we believed we were alone. The ways we looked at one another and all the things we did not say, that we could not say, yet we were always together. Constant companions for months.

She did open up canyons before me. My world changed in myriad ways because of her. The way I saw the world. The connections binding me to everyone, to everything, including my life and American politics, which I could never escape, even though Barack Obama had just been elected.

I didn’t vote because I was in Ireland and because I didn’t care.

And now, ever since meeting her, since falling in love with her, I care too much. Cannot stop caring.

Perhaps that’s the curse she left me with.

But I grew up there, in Ireland, falling in love, believing in the promise of the future, even though I ran from the past.

And I wondered for many years what would have changed had I simply been honest.

Had I said those unspoken, unspeakable, unbelievable words.

All three of them.

And I think again of the things I’ve done and haven’t done. Of the words I’ve spoken and left unshed.

I fell in love with a girl when we were sixteen and everyone knew. Everyone saw. And we pretended no one knew, that both of us didn’t know, because when finally we acknowledged what everyone else already knew, it broke our friendship to pieces.

She did not want that from me and I could not stop my own heart from sprinting madly.

But, over time, through months of absence, I did move past her. Got over her. Stopped thinking about her. Stopped killing myself over her.

But she was broken like me, and she reached out to me after months of silence to ask for forgiveness, to try to heal what shattered.

I told her there was nothing to forgive. Hugged her and she told me she missed me. I lied and said I missed her too even though I could see she meant it. Saw the tears held in her eyes.

I lied and told her we’d talk soon, that we could be friends again, that I didn’t hold anything against her.

That last part was true.

I didn’t hold any grudge or even any negative feelings towards her. I simply severed that part of myself. The part that loved her wilted and died and fell away, so when she wanted forgiveness, it was easy to give.

I wasn’t hurt.

I was a different me with a heart of stone, my heart already breaking for someone else.

I told her about a poem I had written about her and she asked me to send it to her. I did, over AOL Instant Messenger. She told me she cried and that she wanted to frame it and I smiled and didn’t think much about it.

I didn’t see her or speak to her again for three years.

Days before I left for Ireland, I stumbled across her blog and clicked on it because I was bored and maybe kind of lonely and it was 2008 and the internet was still some place where you clicked random links that took you to terrible looking websites.

The first post was about me.

My name was written nowhere, but I recognized myself in every line. Howling into the digital desert, unbelieving that I’d ever see those words. I know she wrote them never expecting me to see them because, after writing hundreds of thousands of words here, I can tell you how awkward I’d feel if, for example, she read this now.

If you’re reading this, I hope you’re doing better now.

I do still think about you and I worry about you though maybe I shouldn’t.

I wish you the best, my dear. You’re in my heart, my dear.

You helped save my life in Korea and I like to think I helped you while you were in France.

And I still love you as a friend who has continued to mean so much to me ever since that day I stumbled across that blog post about me, where I spent the next three hours lying in the dark, alone, miserable, knowing that the then current misery of your life may have been because of me.

Because of the way I cut you out of my life. Severed our relationship.

My absence hurting you.

I mean, it wasn’t really because of me, obviously. I hadn’t been there in years.

But what if I had been?

What if the friend you needed had been there?

Three years before that, you were begging me to see you, to be your friend again, to be the one who you shared everything with, the person who I confided my entire life to, the person who you spilled yourself into.

You still needed that. Needed me.

But I didn’t need you and so I went off and away to different paths of loneliness and misery. And, at the time, some part of me still must have felt betrayed. Afraid to share my heart with you once more.

And perhaps it all would have been so different had I not lied. Had I embraced you and become your friend once more.

Writing that message to you days before I left for Ireland, running from different heartbreaks, remains one of the more difficult things I’ve ever written.

I don’t know what I said anymore. I would like to read it, honestly. Same with that poem I sent you. I don’t know where it went or what it was anymore.

I remember it wasn’t sad. The poem. It was, in a way, joyful.

But your blog brought me back to you and I reached out, responding to your howl.

And we’ve mostly been friends since. Sometimes good friends. Sometimes bad friends. But we don’t talk anymore and, really, honestly and truly, I just hope you’re doing well.

That you’re happy.

And if ever again you need a friend, I’m here.

what he cannot give himself

After Chow ran from the original Li-zhen from In the Mood for Love, he went to Singapore. There, lonely and broken, he lost all his money gambling and kept returning to the casino to try to win enough money again for him to return home.

There, he sees a phenomenal gambler, a woman who wears a black glove. Gong Li at her most gorgeous, her most femme fatale, her most shattered.

A dark, secret past. Everyone knows the horror of her past, but no one knows what it is. Only that she ran away from something that still haunts her.

Don’t we all.

Are we all not haunted by the things we cannot speak, by the lives we cannot stop living, by the dreams and loves draped from out shoulders, tattered by weather and time, by the calamity of living.

I shuddered when she cried, when she didn’t say goodbye.

Eventually, they meet.

She takes pity on him after discovering why he gambles so desperately, even after losing so much. Agreeing to help him win back his money, she makes him promise that, once he wins enough to return to Hong Kong, he’ll quit gambling.

He agrees.

She tells him her name’s Li-zhen.

They become lovers over time, as she teaches him how to win, but she never reveals herself to him. Never tells him anything about herself except that she’s from Cambodia.

Always, Chow wants to dig into her past. Discover who she is, truly. Finally, she makes a bet with him. They each draw a card. If his card is higher than hers, she’ll tell him everything.

Of course he loses.

When he wins back all his money with her help, he begs her to come with him.

She refuses, tears in her eyes. And then she makes him gamble it all again.

One more draw of cards.

If he wins, she’ll go with him.

When he leaves, he leaves alone, and she weeps.

“Take care. Maybe one day you’ll escape your past. If you do, look for me.”

After completing 2047, he returned to Singapore to try to find her, to tell her that he understood why she wouldn’t come with him. She saw what he didn’t.

They always do. These people we throw ourselves recklessly, hopelessly into, telling ourselves that we’re over the past, over the heartbreak, the loss and horror.

He was still too in love with the original Li-zhen to ever truly see her, to ever fully be with her. Had she gone with him, he would only have tried to relive what he had had, only try to imprint this new Li-zhen over the one he lost.

How many women did I—

Who could help me forget—

How could I—

He cannot find her in Singapore.

He fears she returned home to Cambodia and was killed in the scourge of violence.

The night before Bai Ling leaves for Singapore, Chow eats dinner with her again.

This time, she insists on paying. She pays with an envelope full of ten dollar bills that she gives to him. The discerning reader may remember where those came from. He walks her home, the way he did the first night they had sex, the first night he paid her. Once at her apartment, she begs him to stay the night.

One final chance. One more opportunity to heal her.

To maybe heal himself. To find himself in the love she begs for.

Come to me.

Run to me.

Be with me.

Please.

Just for tonight.

One more night.

One last chance.

Please, my love.

My heart.

Please.

He tells her that she once asked him a question that he finally has an answer to.

Is there anything you won’t lend?

He says he now knows the answer to that, and he leaves.

childhood’s end: part four

My wife doesn’t care for movies. She’d rather watch ten episodes of a TV show than sit through a ninety minute movie.

Apparently almost everyone is this way now, but I find that movies remain forever in my heart. I spent my life watching them mostly alone, and I watch them alone still, for the most part. I often find movies that I think she’d love and set them aside to watch with her, but these movie nights rarely materialize and so these movies go unwatched.

But sometimes my love and desire for movies becomes so great that I find the perfect movie to watch with her, knowing she can’t refuse, like, a Sandra Bullock romantic comedy or Mama Mia and so on.

And even though I don’t really want to watch those movies, I put them on because I want to watch a movie.

Because I want to watch a movie with you.

Any movie.

It doesn’t matter, so long as you’re there with me.

Movies have meant everything to me. They taught me to love. Taught me to be myself. More than books or games, I have been made of and by movies.

Even those novels I wrote so long ago, that I’m now giving away to everyone reading this now. All those novels were inspired by and exist because of movies.

Movies like In the Mood for Love and 2046.

Every six month, I rewatched these two movies. I did this for seven years.

I needed them. Held onto them like our sons hold onto their blankies.

These visions. These films of Wong Kar Wai. They became a totem, a seal, a security, an opportunity to weep privately and alone. They comforted me in all their tragic heartache.

I felt as one with them.

I was because of them.

Until I met you.

I still love the movies. Still feel them in my blood and bones.

But I no longer need them.

I no longer even need these dreams of Wong Kar Wai.

And since we first watched In the Mood for Love together, I haven’t watched any of his movies, excepting The Grandmaster when it came out. But I haven’t needed him. Haven’t needed to hold my heart together.

I’ve had you.

Your little hands.

Your heart.

And so returning to Wong Kar Wai and reliving these movies has been a portal cut through time, connecting me to the past selves who loved hard and recklessly, who sought death and destruction but hoped only for love, for beauty, even if only a beautiful death.

For I thought I’d be dead by now. Dead a long time ago.

But then there was you.

And that moment of perfection—the one I told you could only ever be temporary, transient—has been spread over the last decade.

Goodnight, my love, my hearts

My first nephew was born days after I arrived home from Korea. He came six weeks early and when I went to see my sister, to see him, he was connected to wires, plugged into machines.

My own son would spend a month in the same situation ten and a half years later. A month after my nephew was born, my dog died.

The Winter Solstice. Six years later, my first son would be born on that same day.

My friend was planning on going to France to visit her longtime boyfriend, but he had just broken up with her. Tickets bought, she’d be there for six months. She asked me to come visit her and I had nothing but money and time so I decided to go.

And because it was February and Paris was somehow colder than Minnesota for maybe the first time in history, I headed south to the coast. After spending the night at a holy fountain to collect holy oil for my mother, I went to Toulouse where an act of terror was about to happen, where I spent four days mostly in bed due to illness, where I got bedbugs.

Then I headed to Nice where I landed in a hostel room with a beautiful stranger.

About three years and three months later, we’d be married.