When Chelsea and I moved into our first home, the only furniture we had was my bed, which we put on the floor in what would become, one day, our master bedroom. We also didn’t have internet for the first month because the internet provider told me they couldn’t come set up our house for a month1.

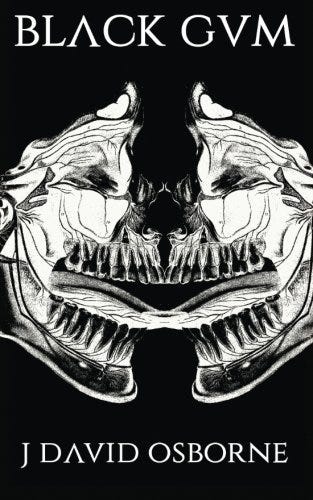

One of the first nights we lived there, I woke up at 3am for no discernible reason and couldn’t go to sleep. I hadn’t yet moved all my books into the house because I didn’t have bookshelves for them. But J David Osborne had stayed at my previous apartment for a few days while he was in town and he gave me a copy of his new novel Black Gum, which I happened to have with me in the new house. Possibly on accident.

I got back in bed, thumbed on the flashlight for my phone, and started reading.

It’s a short book. A small book. Most if not all of the chapters are under three pages, which gives a sort of momentum to the physical act of reading. The pages fly by rapidly and before the sun was up, I had finished.

My phone ran out of batteries and I went out onto the deck in the dawning light of the day to finish the last few pages.

I loved it. I love it still. I’ve talked about it before, but it really is one of the books that changed my own relationship with my writing.

A few years later, J David Osborne’s Broken River Books published Heathenish by Kelby Losack. I’d read a fair amount of Broken River books so I thought I had a general idea of what to expect. At the time, Broken River was mostly known for crime and crime adjacent novels with the occasional weird and wild triumph. Even so, here was something new. Something strange and raw and vulnerable.

Hoodrat poetry. Apocalyptic romanticism. A story about love and friendship and just trying to get by and maybe even keep your head twisted on right for long enough for someone to save your life.

I was on vacation with my in-laws in South Carolina on the Atlantic Coast and, again, I was up late into the night reading this sloshing mess of language and hope dressed in vomit stained overalls.

While Heathenish and Black Gum aren’t especially similar, they do sit right next to each other on the bus. In the intervening years, the only other books that come from this place and sit on this same bus were written by J David Osborne and Kelby Losack.

J David Osborne and Kelby Losack have invented a new way of telling stories by packaging familiar tropes into stories about people who don’t often appear in books as anything but villains or pitiable creatures.

I started calling it Walmart Noir.

Their characters and the worlds wrapped round them remind me of big thrift store couches that filled the houses of my friends. They remind me of taking the bus all through St Paul and Minneapolis with my friend who was temporarily a dealer. Reminds me of the time that same friend almost got his ass kicked while we were on mushrooms because he asked some dude if he could believe how sweaty he had gotten.

There was a day full of hilarious calamity that ended up with me swimming in a lake of muddy water with aviators on while I swam as far out as I could, hallucinogens powering my thoughts, and told my friends I was swimming to the sun and how I got so far out that I couldn’t hear anything but myself.

Out there in the middle of the lake hearing only me. Being only me.

I looked back to shore, so far away, and saw my friends sitting there like nothing had changed. Like I hadn’t just reached the sun and some new frontier of self, but instead was maybe 200 feet out, treading water while they did whatever they were doing.

Reading Losack or Osborne immediately brings me back to the years I spent behind the Blockbuster desk, checking out movies to people who dumped all their anger on me because they couldn’t throw it at the boss they hated or their wife or kids. My nametag was a target on my chest that proved irresistible to the angriest men and women in my city.

But, sometimes, I’d meet a former Hells Angel who gave me a first edition of Hunter S Thompson’s Hell’s Angels and a VHS of Charles Bukowski’s Barfly.

Or the time the local rapper asked me for a movie recommendation and I gave him a few while I was walking the store after my shift ended, looking for whatever movie I’d watch that night. When I got outside, he invited me to get high in his car and listen to music. Didn’t know at the time we were just going to listen to his terrible mixtape for an hour, but that’s how life goes sometimes.

Then there were the times I went to pick up lunch at another nearby store where people also wore nametags that became targets for the anger of every man, woman, and child who crossed the store’s threshold. I’ll always remember how kind and friendly they always were to me while I wore my own nametag. A comradery of the wage worker. An instant kind of understanding between us because we would spend every day in our respective stores being yelled at by people who didn’t need to wear nametags but were so frustrated and disappointed in their lives that they needed to unburden themselves on anyone who couldn’t materially harm them.

I’m reminded how my boss made me follow any black men around the store to keep him from stealing while rich private school kids shoplifted videogames.

Walmart Noir isn’t just about these people or these moments - it’s obsessed with them. Rather than lean into the crime or the hard men and dangerous women typically dominating noir and crime fiction, Osborne and Losack focus on these moments in between. Quiet moments of small humiliation and the fragile moments that make your heart soar.

Slice of life as a genre has grown in popularity in recent years, but it’s typically associated with other genres. Cozy fantasy fiction and farming simulations have become tiny juggernauts in their respective fields and genres as literary fiction has shifted more into the obsessive internal landscape of vain narcissists living in New York.

Walmart Noir pulls away from the fantastic but especially from wealth and prestige. Its characters don’t have time to live inside their heads: rent’s due. Their characters don’t mill about with editors and other writers or artists chewing xanax to deal with the yawning ennui that dominates literary fiction about young people - they’re busy trying to rustle up anything that’ll pay for the next hit, the next beer or pizza.

And perhaps this is why I feel it’s so fresh and wondrous.

It’s fiction written with sharp, dynamic prose that isn’t about the travails of being an artist or the disappointment of never living up to the potential people see in you.

Walmart Noir is just about people, in all their humor and heartbreak.

These books are often hilarious and often grimy and even grotesque, but there’s a current of hope even though everything feels like it’s constantly falling apart.

And I like that.

I like it a lot.

This was a filthy LIE and I will never forgive Centurylink for wasting my time or providing absolute terrible internet

Your metaphor of the nametag as target is brilliant. Anyone who has ever worked a service job understands.

“Walmart Noir” is probably what I’d write if I ever actually did write some fiction.