Happy Valentine’s Day. I don’t have anything especially romantic to write for today, but you can check out this post from last year.

Or if you want something more recent and specific to me, this should serve.

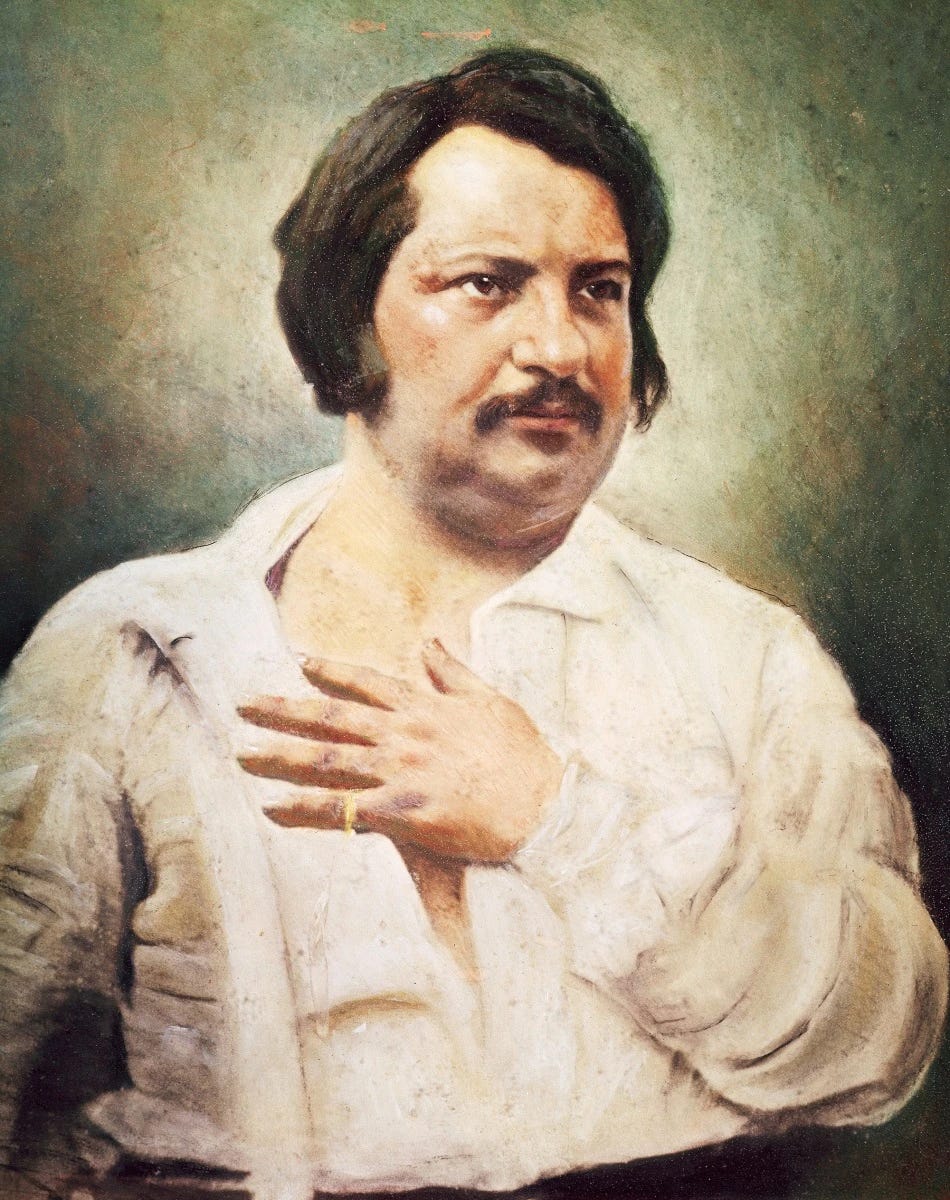

Honore de Balzac’s Lost Illusions follows a young aspiring poet as he moves to Paris to become a famous poet. Shortly after arriving and having no such luck, he is offered a job as a journalist. He’s told this is the natural trajectory of a career in letters. Along the way, he becomes involved in theatre criticism where he witnesses the way talent and aesthetic beauty have little to do with success. More important is having the right journalists on your side.

At one play, a commotion breaks out because brutes jeer and hiss at the play on stage. What he learns is that those brutes were hired specifically to disrupt the play and lead critical reception in a specific direction. While this bothers our aspiring young poet, he’s assured that this is simply the way of things.

Literature, the lesson goes, is not a meritocracy. It’s a seething political cauldron dominated by money and promises and connections.

That book is 200 years old, fella

A certain massive game was recently released and, depending on your bubble, it’s either the biggest and bestest game ever or it’s the worst game ever and not worthy of discussion. If you’re just a regular person who occasionally plays videogames, you probably have no idea what I’m talking about.

Which is fine.

This essay isn’t really about Hogwarts Legacy but I did get called a libtard this weekend on the world wide web because of it, which got me thinking about the antagonism between gamers and the journalists who report on games. This isn’t a history lesson because I really just want to talk about the concept of unbiased reporting and then I want to talk a bit about something I wrote about over at the Bestseller Newsletter.

what’s all this, then?

To some, this image says it all.

What I find interesting about the various reviews about Hogwarts Legacy is how little you actually learn about the game from reading reviews. IGN’s review laid out a host of issues with the game before giving it that 9/10 because it allowed him, finally, to roleplay as a wizard at Hogwarts.

The Wired review, whether rightly or wrongly, cannot ignore the real life problems the author has with JK Rowling. Of course, if you already dislike someone, any minor annoyances or aggravations begin to balloon and seem emblematic of everything you already dislike about such and such.

In both cases, who the person is outside the game they’re reviewing leans so heavily on the review’s score that they both serve their own specific audiences perfectly.

People who hate JK Rowling can point to the Wired review as proof that they’re right. People who are indifferent to the controversies surrounding Rowling can point to the IGN review and feel justified in spending their dollars and time in this world.

Even more interesting to me is that several videogame venues flat out refuse to acknowledge that Hogwarts Legacy came out.

I find this kind of bizarre, and the reasoning behind it is sort of a circle. I’ve seen journalists claim that there is no reason to discuss a game this big because it will be everywhere anyway.

I mean, imagine if no one had written about Skyrim in the last decade or Breath of the Wild in the last five years or if no one even mentioned Elden Ring last year.

The casual gamers would be baffled by the dearth of search results when googling these games.

But the idea that something so noteworthy doesn’t need to be discussed feels like the worst and weakest argument possible here. It would be like if American news journalists didn’t bother to cover The State of the Union because enough people watched it themselves and didn’t need any critical analysis to accompany it.

The other reason I’ve seen for ignoring it is that discussing the game may lead to real life harm by further enriching Rowling, whose controversies revolve around her views on gender and transitioning.

Personally, I don’t think this is a good reason to pretend like one of the (likely) bestselling games of the year doesn’t exist. I do think it’s a good reason to actively position yourself in opposition to her (or in alignment with her, depending on what you make of this). This is, perhaps, the best time in recent years to analyze, discuss, tear apart, recontextualize, and explore topics of gender in popular culture.

The game could be a vehicle for you, the writer, to explain the debate in a historical, political, and cultural context all while tricking the regular googler of game information into reading about this topic that they may say they don’t care about.

Now, there was never a reality in which I ended up playing this game because I just don’t care about Harry Potter1 and don’t really care for open world games (more on this at some future date).

To be honest, I don’t even really know anything about the game.

As for JK Rowling—

Yesterday, I was at Barnes and Noble with my family. Maybe 10% of the store was devoted to Harry Potter. I believe this tells you everything you need to know about the actual scope of this controversy and the difficulty of materially harming people this rich and famous. I’ll circle back to this in a bit.

Bias, baby

Many, many people seem to believe that news should be unbiased. I think this is a worthy enough goal, but I also think it’s impossible.

Often what people view as unbiased is reporting that reinforces the status quo. It’s completely uncontroversial reporting because it falls neatly in line with what the majority of people believe is true about whatever is being reported upon.

Not so recently with regard to videogames, this kind of unbiased reporting reinforced the following ideas:

Violence in videogames leads to real world violence, including mass shootings like Columbine

Videogames are addictive

Videogames lead to antisocial behavior

Videogames are gateways to extremism

There are many more unbiased claims taken as fact by your parents and grandparents about videogames.

But to take a step back: is it possible to be unbiased?

Um, no, to put it simply.

You are a walking container of biases, based on the totality of your experiences, beliefs, and so on. You can do your best to write as factually as possible without any analysis or commentary, but your bias will still extend even to the stories you choose to cover.

For example, had no one called me a libtard, I may not have even written this very essay you’re reading.

As a videogame outlet, your 100th post about Destiny is a product of bias, as is your 1st post about Cuphead. Choosing to cover this rather than that is a bias.

But so where do the relevant biases come from in videogame journalism?

As videogame journalism has grown up and expanded, we now have people almost exclusively covering eSports or retro games or indie games and MMORPGs and on and on, but the bulk of reporting still revolves around AAA games.

But even there, we have people like Jason Schreier whose reporting on crunch has been so important that it essentially opened up labor reporting in the industry. This has not come without consequences, mind, and the biggest one is access.

The Access Trap

We recently began watching The Lou Grant Show because we love Ed Asner and The Mary Tyler Moore show. The Lou Grant Show is very difficult to find in any legal way, but it is watchable if you go to youtube dot com. The reason for this, incidentally, has to do with Ed Asner’s political views, which caused the show to be canceled even while it was draped in awards and the stigma persists to the point that this much lauded show has been culturally forgotten.

I mention this because the very first episode has to do with reporting on the local police precincts. There’s whispering about some real muck, but the paper’s police reporter has been successfully sitting on the story to keep it from coming out.

You might ask why. Why would a reporter not report on their relevant beat?

Well, he’s friends with the cops. They’re friends with him. Further, because his beat is the cops, he risks his career by exposing their crimes (in this case, a story of cops raping underage girls—first episode of a primetime TV show that was a spinoff from a sitcom!).

Without access to the cops, he has nothing to report on. He needs the cops to like him so that they’ll talk to him so that he’ll even have stories to write about.

We see this over and over again in national US politics. If you wonder why conservative venues so rarely report on controversies surrounding conservative politicians, this is why. The same is true, of course, with liberal papers and the Democrats.

But to bring this back to videogames: videogame journalists rely on access to the developers and publishers of videogames to write their stories. Kotaku has been blackballed by various videogame companies due to their reporting, which means they don’t receive review copies of new games, which means they can’t report on games until after they’re out and have been out for days if not weeks. It also means that the developers themselves are very unlikely to talk to reporters from Kotaku because they may face negative consequences to their career.

And so there is a wheel being continually greased by journalists in every industry because their careers depend on that access.

It is worth asking: is it possible to be unbiased when your career may rely upon giving a positive review to a game or at least covering the game in such a way that it won’t alienate the owners, directors, and developers of a game?

This goes beyond individual journalists, too. It goes up to the Editor in Chief but even beyond them to the owners of the company reporting on the industry.

Here we get to another wrinkle in the game of bias: these videogame venues are not scrappy startups, for the most part. Many of them are owned by massive multimedia conglomerates who may have a stake or even ownership over the videogame company publishing the game being reported upon.

This is rarely mentioned.

In this same episode of the Lou Grant Show, when the cop reporter finally writes his piece on the way these cops have been raping underage girls and even discusses his own role in covering up this story, the owner of the newspaper decides to kill the story because, as she puts it, there are too many negative stories about cops.

Polygon, one of the biggest sites for videogame journalism, is owned by Vox Media which is owned, in part, by Warner Bros Discovery, which is also owns the production company for the Harry Potter film series, which was also the publisher of Harry Potter Legacy.

Some may call this a conflict of interest.

And then, even setting all this aside, we have the problem of capital, which is why I was not surprised to see Harry Potter dominating a significant portion of the Barnes and Noble we went to last weekend.

When a game is a massive success, it affects your bottom line when you choose not to cover that game. This is why game studios refusing to send Kotaku review copies matters.

Kotaku makes money through advertising. When a game like Elder Scrolls 6 comes out, those venues that received the early copy will be able to have their review ready days before the game comes out. The venues that have those reviews up will receive millions of clicks while the places that don’t will receive millions fewer clicks, which means there’s less money generated by ads, which means the newsroom may be downsized or scrapped entirely by the parent company.

It would be one thing if videogames only took a few hours to experience, because then the review could be just a day or two later. But a game like Elder Scrolls 6 is going to be somewhere between 30 and 150 hours to complete, depending on play style. Which, in the case of a later review, will be rapid and feverish.

Then there are aspects of the criticism/developer cycle that are further complicated. Some gaming companies give bonuses to their developers based on the metacritic score the game receives, which means when you write a damning review, you are literally causing the workers—many of whom crunched 12+ hour days 7 days a week for months—to make less money.

Yes, that’s not a fair way to put it since the companies could just pay a fair wage, but it is definitely a way that game studios try to strangle critical reception while also deliberately underpaying their workers. It allows them, too, to pit the workers against the people reporting on the industry.

“It’s not us who refused you your well-deserved bonus. It’s those damn journalists!”

The whole model of internet writing revolves around advertising or subscriptions and so when a venue chooses not to cover Hogwarts Legacy, they are making a very big decision, which will harm their bottom line in significant ways.

Now, someone will say that this will be balanced by the praise they get from people on twitter.

But this is so absurd that it really can be ignored because the thousands of people protesting on twitter will be washed away by the millions of people who have never even logged onto twitter once.

I mention this all because the fact that we get negative reviews of games at all is a bit of a wonder, considering all the many factors that would lead venues to be positive and report only the good.

Critical disagreement is good

I add this image here again because this image highlights something that is good.

While the people posting it intended to use it as a sign that Wired was motivated by reasons that have nothing to do with the game itself, I would say that this shows a healthy critical environment.

When Ulysses was published in 1922 and while it was being serialized in the years leading up to that date, there were many, many scathingly negative reviews. There are critics who hated The Beatles or 2001: A Space Odyssey. There were also many reviews of all these things that can best be described as a shrug.

Of course, as we know, there were also reviews that understood they were experiencing something new and glorious and important. And now, all these decades later, these various works have been contextualized and placed in running lists meant to order the Bestest of the Best.

I’m not going to say that there is no political motive at play in Hogwarts Legacy. The truth is that these numbers are likely manipulated on both sides and for opposite reasons but the same end goal: to determine the critical reception of a piece of media.

We saw it in the 1830s with de Balzac’s Lost Illusions and we’ll see it again and again for as long as art is being made and artists rely on critical and public perception to make money.

The people who want to show solidarity with Rowling or against cancel culture or twitter scolds or for any of the reasons outlined above are definitely pumping the numbers on one side just as there are people on the otherside of the political and cultural divide trying to weigh down that metacritic score.

This, sadly, is the truth of almost all pieces of media that manage to be sucked into the Culture War.

Is Hogwarts Legacy fun or good?

You may be shocked to learn how few people heavily invested in discussion about this game are even interested in engaging with this question.

But if we set Hogwarts Legacy aside and discuss games more broadly, we need to understand that critical disagreement is good. Often it’s even good for critical perception to be out of sync with public perception.

We want our ivory tower dorks to write signals in the sky about what they deem as culturally significant, not because they’re right (they’re often wrong2), but because they tell us something about a specific time.

It’s possible that Elden Ring, the biggest game of 2022, will be re-evaluated as a failure in 20 years and it may even be completely forgotten in another 20. It’s possible that some game that was critically reviled in 2017 will be rediscovered in 2054 and deemed not only a classic but one of the most significant games of the 21st Century.

If that sounds outlandish, consider the case of Herman Melville3.

People are often wrong and that’s fine. The public crusading against women or queer people or people of color in games in 2012 may be quietly embarrassed and ashamed of themselves right now in 2023.

But if videogames are going to grow up as an artform4, we need to accept and encourage critical disagreement. Even vociferous critical disagreement! I want people to fight over the quality of games the way people have fought over the quality of movies and music and TV and books for decades and centuries.

But I want to see it as something other than brand loyalty as demonstrated by the Console Wars. Nothing could be more boring than arguing over Sega v Nintendo or Playstation v Xbox, but, buddy, if I ever see a fistfight break out over weapon durability in Breath of the Wild, I’ll know we’ve made it.

Because, if this newsletter is anything, it’s an attempt to contextualize art within biography. And I do think videogames are art. And I think art is worth fighting over because of the way it shapes our lives.

My own views on the politics of Harry Potter will be explored at length this year as I discuss the books when I reread them for the first time (the first just arrived from the library this weekend so expect the first post in a few weeks)

Who won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1952, for example? If you look it up and say to yourself, What even is that? Well, there you go.

A very successful writer of popular fiction, he wrote his third novel, Moby Dick, with grand aspirations. It flopped so horribly both critically and commercially that it destroyed his career and ruined his reputation. His books fell out of print and he finished his life as a customs officer on Ellis Island. Seventy years after its publication and thirty years after Melville’s death, the novel was revitalized and championed by people like DH Lawrence. It’s now considered one of the greatest and most significant novels in the English language.

I have more to say about the divide between videogames as product and videogames as art, but we’re already getting a bit long. I also wanted to talk about the politics of gaming and a dozen other things. Maybe some future date.

I'm ~26 hours in Hogwarts Legacy now and all the furor is really getting hilarious to me, because...it's a thoroughly average game. It has some real highlights, but it lacks a lot of polish. It's not bad--it's very enjoyable in many ways--but it's not transcendent either. It's...fine. Wired could have earnestly given it a 3/10 or a 4/10 review and I wouldn't have batted an eye; depending on how you personally value things, that would be a fair score. And doing so probably would've done more to sway people away from the game than the obviously political review they gave.

Areas of journalism that require continual access always seem the worst (sports journalism, gaming journalism, White House gossip, etc). It's a problem that I haven't the slightest idea how to resolve.

Ed, this was just a brilliant essay. Your exploration of why it’s impossible to remove bias from journalism is excellent, but I especially love your turn at the end--that it’s ok and even good for critics to argue and be wrong, just so long as they’re not serving corporate interests.

And your point about the influence of advertising on editorial content reminded me of how, in the 90s, Ms Magazine tried to reboot, but without advertising. They published an editorial listing a few of the ways advertisers could influence content, which was eye-opening to me. Much later, when my kids were little and I subscribed to Parents, I noticed that at least twice an issue there would be an article or item that urged parents to cover their kids in a shot-glass worth of sunscreen every time they went outside, and to use up a bottle of sunscreen every day. “Aha!” I thought. “I sense the hand of the advertisers in these insane recommendations!”

Sadly, the advertising-free Ms Magazine folded after a few years. Noble in its conception, though.