I’m e rathke, the author of a number of books. Learn more about what you signed up for here. Go here to manage your email notifications. I also began a new substack highlighting obscure books in the public domain.

wake up, were you having a nightmare

2019’s Katana Zero is primarily played through one button. Yes, there are two other buttons you’ll use frequently, but this is a game built around a single action. While this makes for a streamlined and simple playing experience for the player, it’s also full of pitfalls the size of canyons.

If the player is only doing one action, that action better feel better than just about anything else.

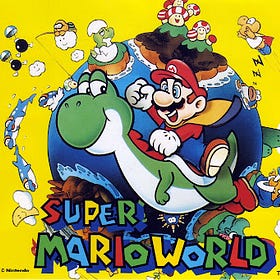

I’m talking Mario’s jump levels of feeling good, which is something so essential to gaming history, in my view, that I’ve written a whole essay and talked about it for an hour on a podcast.

mario, daddy

I remember Mario the same way I remember my siblings. They’ve always been with me, since memory first sparked and began eating itself like Jörmungandr. I’ve been thinking a lot about Mario, which I’ve only been doing because I’ve been playing a lot of Mario with my son, which I do because I love him and myself.

And what is that action in Katana Zero?

Slashing your sword. Or, to say it slightly differently: murder.

You’re a hired killer. An amnesiac whose story is revealed slowly as you progress through the story. And the way you progress through the story is murdering buildings full of people. You’re given choices at the end of these massacre mausoleums and dialogue trees branch out a bit in between your killings, but the entire game is built on top of making this single action—murder—feel as good as Mario’s jump.

And, well, before we get to the story and all that, I got to hand it to them:

Goddamn does it feel good.

Katana Zero is a 16bit looking sidescrolling beatemup that, I think, shares a lot more with sidescrolling platformers like Mario and Super Meat Boy than, say, Streets of Rage II or Ninja Turtles or even Ninja Gaiden.

The game is meticulously structured with each button tap meaningful, that rewards precision and control.

But first we begin in chaos.

Action is rapid and, at first, frenetic, but button mashing will lead you to failure after failure. Thankfully, the game teaches you how to play as you go. Which is to say: the game makes it easy to successfully murder enemies at first. But even when you fail, you’re quickly transported back to the beginning of the stage through a rewind, showing you exactly how you failed once more.

Within seconds or instantly, if you skip the rewind animations, you’re able to make another attempt. This rapid reset allows the game to feel like you’re always making progress, even as you fail repeatedly. Every time you die, you’re just a moment from your next attempt.

And you will die.

A lot.

So many times.

But the vicious smoothness of the kill, the way your slash propels you towards your next kill, the way you can slice bullets right out of the air feels so good, so clean, so beautiful that you can’t wait to make it through each stage flawlessly.

Which is what the game demands.

One hit. That’s all it takes for you to die.

And so you learn precision. You learn patience. You learn strategy.

And you learn it through a thousand different deaths.

In many ways, the game it is most similar to is 2018’s Celeste, one of the best platformers in decades not made by Nintendo or starring a plumber.

Like Celeste, Katana Zero is deliberately nostalgic, at least in palette and graphics. It reminds you on purpose of games decades gone. The ones you played in the primordial soup of your memory. But while the games look 30 years old, they are thoroughly modern, building off those many decades of gaming history to find a near perfect mechanical balance. Both are built around their single action—jump for Celeste and murder for Katana Zero—but also allow for a compelling dash that makes you feel so in control, so powerful. On top of that, both allow for an immediate reset to the beginning of the stage upon failure.

And so even if you die dozens of times on the same stage, you never live long with your failure. Rather, you’re slashing right into your next failure, dreaming of success. And all the failure, all the dying, all the internal screaming, makes every success feel so fucking good.

It’s indescribable, honestly. If Celeste has anything on Mario 3, it’s that the push and pull of failure and success feels better in Celeste, in part because of the pace of the game.

And the same is true of Katana Zero. Each stage, when executed flawlessly, should take you, at most, a minute. But many—most, probably—take maybe 15-30 seconds to complete.

Because the stages are so rapid and so short and resets are immediate, you are always only a few seconds from success, even after your 30th consecutive failure.

But if this was all the game had, I wouldn’t be writing about it. Lots of games feel great to play—though few feels this good—but Katana Zero struck me in several ways while I murdered my way through its story and it has remained with me in the months since beating it.

In contrast to Celeste, which has often been praised for its story (which is fine, but I’d sum it up as: depression sucks and we are sometimes our greatest enemy but in embracing our whole selves we can come through the otherside rather than kill ourselves), I felt that Katana Zero had much more to say while still telling a very personal story.

Despite being a legendary and mysterious assassin swinging a sword through enemies with machine guns, the world of Katana Zero is a cyberpunkish dystopia. What law exists means little to anyone. Most people live in slums, suffering, while crime syndicates and corporations rule the world.

There is a land of luxury and there is a land of misery and they share the same city limits.

The City and the City by China Mieville imagines a world where two cities share the exact same physical location but people from either city behave as if the other does not exist.

And this is, always, the story at the foundation of cyberpunk. There are two worlds. They just happen to be the same world.

The rich live in one. The rest of us trudge through the mud and the blood and the misery.

The game plays out through the platforming stages mentioned above but also scenes between the protagonist and his therapist, who also pumps him full of a mysterious drug and sends him on his murdering missions. In these conversations, you can choose to be combative or passive, assertive or inquisitive. This is also where you begin to understand the world and the protagonist.

Along with these scenes, we also get moments of our protagonist getting shitfaced at a bar where he’s harassed by others for not supporting the veterans of the previous catastrophic war. When you tell him you’re a veteran of that war, they don’t believe you.

You meet other veterans, living on the street.

Along with that, you befriend a young girl who lives next door. The child of neglectful parents, lost to their addictions, she clings to you because of the very small kindnesses you show her.

At least at first.

As time goes on and the story deepens and you understand your place in this world, in this story, your attachment grows.

I mean you.

The player.

You grow attached to their relationship, to the vulnerability shared between this miserable child and this horrifying killer, especially as you begin to put the pieces together to understand who he is, why he is, and how he got here.

A past of unspeakable horror and violence. The corporation that stole your humanity, made you into a living weapon. Vicious, unkillable.

All your choices have been writ for you and so you finally try to break the script. And instead of becoming free, you come to a cliffhanger where you stand on the brink of horror and terror, with all the fleeting glimpses of a life, of love, of companionship, stripped from you.

Despite this, there’s quite a lot of humor. Black as night, but funny all the same. Even the simple touch of having our protagonist put in earbuds and find a song to listen to while he murders his way through a building is a very specific kind of funny that works with the violence but also balances it, even as it unhinges the protagonist further.

To say more would be to say too much. Perhaps I’ve already said too much. But Katana Zero is a game that trusts you to put the story together through the crumbs dropped along the way to the Witch’s cabin in the woods.

But the more you learn, the more you understand how beautiful the mechanics of this game are. How the story itself is baked into the mechanical design of the game.

And this is beautiful to me.

That you could understand the story simply by paying attention to the mechanics of play. Which is something so novel yet so brilliant that I wish more games did this. That more games trusted the players enough to understand the story being told in front of their own eyes.

But this perfect blend of story and mechanics is, to me, the ideal structure of a game. Where the script, the cinema, and the gameplay all interlock like gears.

My novels:

Glossolalia - A Le Guinian fantasy novel about an anarchic community dealing with a disaster

Sing, Behemoth, Sing - Deadwood meets Neon Genesis Evangelion

Howl - Vampire Hunter D meets The Book of the New Sun in this lofi cyberpunk/solarpunk monster hunting adventure

Colony Collapse - Star Trek meets Firefly in the opening episode of this space opera

The Blood Dancers - The standalone sequel to Colony Collapse.

Iron Wolf - Sequel to Howl.

Sleeping Giants - Standalone sequel to Colony Collapse and The Blood Dancers

Some free books for your trouble:

I had forgotten how amazingly popular Ninja Gaiden (and Shinobi) was!

I played Celeste after Katana, but had the same thought about their similarities. It's just so funny to me how opposite their vibes are though, in terms of bloody killing spree vs. wellness journey. Although I suppose both kinda have imaginary alter-egos...