I Like America and America Likes Me

or, shamanistic artistry; or, vocal tears and reckless love; or, art is a blood ritual

Artist as Shaman

Had it not been for the Tartars I would not be alive today. They were the nomads of the Crimea, in what was then no man's land between the Russian and German fronts, and favoured neither side. I had already struck up a good relationship with them and often wandered off to sit with them. 'Du nix njemcky' they would say, 'du Tartar,' and try to persuade me to join their clan. Their nomadic ways attracted me of course, although by that time their movements had been restricted. Yet, it was they who discovered me in the snow after the crash, when the German search parties had given up. I was still unconscious then and only came round completely after twelve days or so, and by then I was back in a German field hospital. So the memories I have of that time are images that penetrated my consciousness. The last thing I remember was that it was too late to jump, too late for the parachutes to open. That must have been a couple of seconds before hitting the ground. Luckily I was not strapped in – I always preferred free movement to safety belts ... My friend was strapped in and he was atomized on impact – there was almost nothing to be found of him afterwards. But I must have shot through the windscreen as it flew back at the same speed as the plane hit the ground and that saved me, though I had bad skull and jaw injuries. Then the tail flipped over and I was completely buried in the snow. That's how the Tartars found me days later. I remember voices saying 'Voda' (Water), then the felt of their tents, and the dense pungent smell of cheese, fat, and milk. They covered my body in fat to help it regenerate warmth, and wrapped it in felt as an insulator to keep warmth in.

This was how Joseph Beuys described surviving a plane crash in Crimea, though the German military has very conflicting accounts of this1.

Twenty years later, he would integrate this into a work of art called I Like America and America Likes Me.

You can view clips of the performance at this half hour video.

I think you’ll need some context here to understand what and why, unless you’re one of those brave and inquisitive souls who dive into the vapor without a parachute.

If you are, I commend you.

I have always liked and applauded bravery, so feel free to watch this half hour video and meet me at the next sentence.

For the rest of you, some context.

While we’d probably call this performance art, Beuys described it as Social Sculpture, which is certainly a better name. The fact that this didn’t catch on maybe says something to the impoverished aesthetic of the post-war art world.

His concept is farther reaching than most artists. Wagnerian, really. In his view, society at large may be viewed as the great work. Society is art and because of that, artists must become engines of social change. And I find this immediately gripping since I think much of what passes for art and intelligentsia in the world works as a scaffold to brace and hold up the current world and society, the status quo. Rather than break the boundaries of society or even stretch them, many artists—especially of the 21st century—simply reinforce society as it exists. They become a bulwark against change.

The same is true of our public intellectuals and our pundits.

But I digress.

Further, because society is the art, every member of society becomes an artist, shaping the great work.

Perhaps the best and most readily tangible of these social sculpture works is 7,000 oak trees, which I’ll try to explain briefly.

The project began with 7,000 basalt stones being dumped in front of the Fridericianum2 Musem. Each stone was then removed as an oak tree was planted.

In this way, the city of Kassel became the canvas for art. Volunteers, artists, and anyone else was an artist constructing the art with their own hands. And in so doing, these many people contributed something specific to society, turning the land, their city, into a work of art, turning themselves into artists.

But now back to this Coyote.

I Like America and America Likes Me (1974)

This bizarre and abstract work was imbued with meaning if you knew how to look at it.

Beuys landed in New York where his assistants immediately wrapped him in felt and brought him to a SoHo gallery by ambulance where he would spend three consecutive days living with a Coyote. Once done, he left as he came.

Thus and so, he never stepped foot in America except for where he lived with this Coyote.

Beuys remained wrapped in felt, as he was when the Tartars saved his life when he crashed thirty years previous in a genocidal war, and spent the days with the Coyote. He was provided with extra felt blankets and a daily copy of the Wall Street Journal.

Throughout the 24 hours spent with the Coyote, Beuys tried to connect with the animal by repeating symbolic gestures. He wrapped himself in the felt blanket and poked out his shepherd’s cane to give us the strange and uncanny image at the top of this post

The Coyote remained mostly calm, though at times showed hostility. It tugged at his felt cloak and snapped at him here and there but largely got on fine with him being there. Beuys played a triangle and recordings of turbines. Sometimes Beuys copied the movements of the Coyote, moving when it did and resting when it rested.

This whole performance is symbolic and your willingness to engage in this kind of esoteria will either make this interesting or completely stupid and strange. Personally, I’m not one for abstraction, as I’ve said often. Even so, there’s something very interesting happening here, if you’re willing to open your eyes and crack open your sternum.

The whole performance relies on the symbolism of the Coyote.

Transforming trickster god, the Coyote of Native American mythology is like mixing the Norse Loki with the Titan Prometheus and the kitsune of Japan. So not exactly a positive figure but also not a negative one. Rather, an engine of change and transformation. A teacher. A leader.

But that’s too simple.

While the Coyote exists as a mythical figure, it also exists as a real life predator, and this is the view many, if not most, have when they hear the word Coyote and especially when they stare down one of these beasts wandering through their backyard.

So while Beuys Coyote as the soul of America, many saw only an aggressive predator that we need to get the hell out of our towns and cities.

Beuys is asking us to consider all these symbols at once. And in doing so, he’s asking us to find a way through them all.

The performance came at the tail end of the Vietnam War, but also after a decade of transformation in the US. Racial violence and sectarianism continued. We had the Black Panthers, the Wounded Knee occupation, and on and on. Racial and political turmoil dogged us and ran through society.

And so Beuys came as a shaman, hoping to heal us.

Safe to say looking back from today, it did not work.

But it’s the attempt that matters. Prometheus, too, failed. Sisyphus along with him. Our greatest heroes are draped in failure, in their punishments for deigning to save us, to heal us, to defy the gods and fates.

But they tried. They gave what they could, even knowing it may end in tragedy, in eternal punishment.

Life as Art

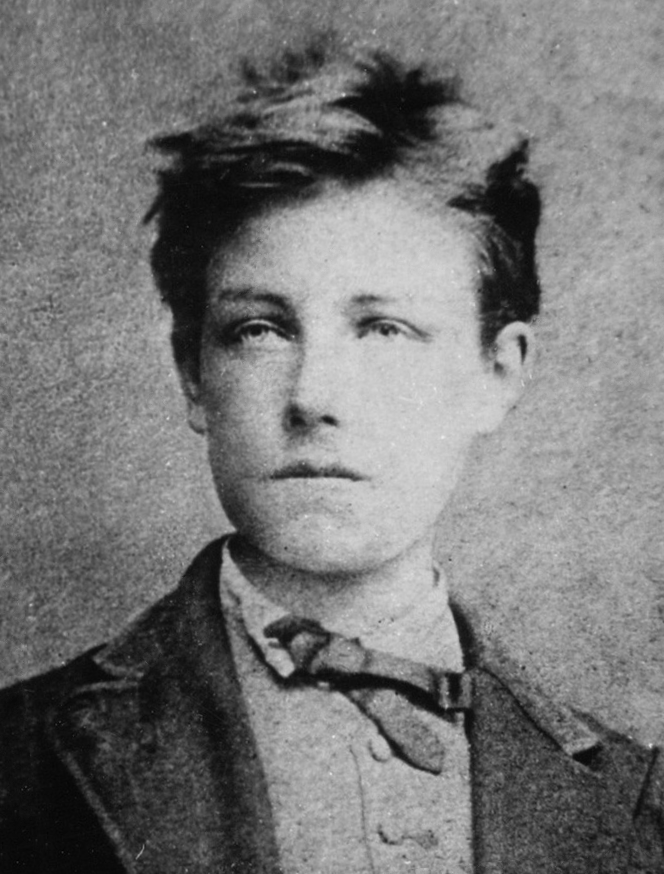

Arthur Rimbaud changed the world before he was twenty and then disappeared into colonial Africa to sell munitions and die of syphilis before he hit forty.

He was a true artistic visionary and, in my view, he built the 20th century, whether anyone likes it or not.

Transgressive not only as an artist but also in life, he was the Platonic ideal of l’enfant terrible. He behaved like an insane person, breaking up the marriage of Paul Verlaine and turning him into his lover but also, in a way, his apostle, before driving Verlaine mad as well, leaving him to rot in prison after he shot Rimbaud in the wrist with a pistol.

Rimbaud lived on the edge of the increasingly mechanized world and though none described him this way at the time, there was something of the shaman to him. Perhaps the holy fool is a better term for it.

I discovered Rimbaud when I was sixteen when I stumbled into the 1995 biopic Total Eclipse starring Leonardo DiCaprio as the young artist and David Thewlis as Paul Verlaine. It’s not an especially good movie, but I found it intoxicating. Not so much the movie as the life it presented.

Art as life. Life as art.

As I’ve said before, I was an apocalyptically unhappy young man. I spent most days wishing I had died, a long time ago, where no one knew me, before anyone knew me, where I was nothing and no one, where I was nonexistence itself, where I could have bled away into the aether, into the vast void burning molten hot at the center of the universe, this galaxy spanning blackhole that we all yet twist round.

The next day, I went to a bookstore and bought the collected poems of Arthur Rimbaud and then ritualistically read them repeatedly for weeks until they carved lesions in my brain where I can still recall passages despite the tattered tapestry of a memory billowing in this blaring gale of experience.

I have stretched tightropes from steeple to steeple; garlands from window to window; golden chain from star to star, and I dance.

For nearly ten years, I reread this body of work, this brief lifetime of glory, every six months. When my life became unbearable, when my eyes bled and I wanted only to drown in fire and drink myself into emptiness, I would open to these poems and stumble darkly through the blaring bright of blistering words burned into my bones, into my steaming blood.

My whole life seemed a season in hell that I hoped to escape yet Rimbaud illuminated my life, gave me a reason, a will, and words. Words to live by.

Words of salvation.

Words like fire.

And I began acting out. Living recklessly. Living hopelessly but loudly. I became, on purpose, a holy fool. Chucking away rationalism in favor of this brute chaos, as if I could transform myself enough that perhaps the world round me would follow, would make space, would tear open just enough for me to walk on fire, to walk through fire, to become the fire itself.

And this is when, perhaps unsurprisingly, I began writing in earnest.

Words have always meant too much to me. The sound of them. Their texture in my hands, in my mouth, the ways they scrape against my eyes, the way they line upon a page, the way they burn and chill, the ways they bounce and radiate.

I hear them. I feel them.

When I close my eyes, there is no blackness.

There is the fire.

I do not think in language but I breathe it. And I sometimes think I turned to words because I didn’t know how else to express this storm, the fire inside me, the fire I am.

Had someone taken me to a ballet when I was fifteen, perhaps I’d have leapt to that stage and turned the fire into movement, into motion, and perhaps I would have found happiness in a more honest expression. Perhaps I wouldn’t have turned myself into a terror in Ireland or Korea or a dozen other countries where I burned and swelled large enough to combust and lose myself entirely.

My life became a bit of a work of art, or at least a partly intentional masquerade. A sequence of presentations of self, of inventions, of interpretations. Life as creation of self, as engine of self, and it all, strangely, became tied up with the Taoism that hit me like lightning when I was fifteen, that coursed through me ever after, and even while I danced from steeple to star, garlanding myself upon the fiery firmament, I was following a version of the Tao that swept into my life like a vision that never blurred or faded from that first time I stared upon those pages and the pages stared back at me, swallowed me, consumed me, remade me with their fire.

Becoming the fire.

An Impoverished Age

The virality of terrible opinions is all the rage and is the curse of the modern digitized age where we must be constantly deluged in people endlessly impressed by AI art turning the manipulation of digital objects into yawn inducing vapor artefacts that will be forgotten the moment you scroll past them and yet the mundanity of this has infected people with this parasitic conceptualization of art as a visual medium where people honestly and seriously consider the reveal of the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park as the last moment when cinematic spectacle could awe us, fill us with wonder.

The person who made this viral opinion would likely believe that they agree with the sentiment I’m describing here, but they are fixated on a tool rather than the craft.

Yes, digital art has come a shockingly long way. I still remember how Final Fantasy X blew my socks clean off but I also remember shrugging at the fidelity of the graphics in something like The Last of Us. And so it’s true that the massive leaps in photorealism has made these accomplishments and achievements less interesting.

But the reason Jurassic Park awes us when the camera turns and shows us a digital Brontosaurus has very little to do with the CGI and everything to do with the narrative grammar and structure. We fall into the reality of this world, the vision and perspective of these paleontologists, and we are struck dumb by this vision of splendor not because of the technology outside the world of the film that produced it but by the technology within the world of the movie that produced it.

We are filled with awe because our paleontologists, who are our eyes and hearts in this story, are seeing for the first time A FUCKING DINOSAUR.

Recall, if you can, those dinosaur books you got from the library as a child. Imagine if those books shaped the direction of your life. You leaned into science and biology, always drawn to a world millions of years gone, buried beneath the layers of skin of the earth. You went to college and then leapt into a PhD program where you studied long dead creatures and what little evidence of them remains. You scoured the world to study bones, to dig them up.

And then, a decade or more into your career digging in the earth, using paintbrushes to carefully remove sand and dirt and earth from fossils, from fragments of bones, someone comes to you and tells you that all your life has been transformed.

You have spent your entire life studying dinosaurs. Creatures so long extinct that it literally boggles the mind to consider what 65 million years actually means. And then this weird rich guy with a fun hat and a fun personality brings you to his secret island and he shows you a goddamn fucking dinosaur that you witness with your own goddamn eyes.

So, no, it is not that digital art awed you in the theatre in 1993 when you were six years old sitting in the dark between your dad and older brother.

It was the dinosaur.

In 2013, when they rereleased the movie, I went to go see it with my roommate. I hadn’t seen it since we wore out the VHS in 1995 but I remember distinctly three seconds before the dinosaur was revealed to me again.

A terrifying thought gripped me: what if this looks like shit?

I mean, the CGI was twenty years old. I’d seen graphics from 1993 and graphics from 2013! The thought that those 20 year old digital dinosaurs would hold up seemed almost impossible.

And yet they did. They do. In some ways, they look better than what passes for CGI in 2025.

But, again, the success of this moment is narratively driven.

Yes, it would not work as well if the dinosaur was a Hensonian puppet or if the CGI looked like Final Fantasy VII. I mean, in all honesty, if it looked like that it would probably fall flat.

I’ll give you that. The dinosaurs had to look passingly real.

But the thrill we felt and still feel in seeing the camera pan over to these monstrously large beasts has everything to do with narrative fulfillment rather than CGI.

What I mean to say is that the reason you no longer feel awed by the spectacle of film is not a technological problem. It’s a narrative problem. A craft problem.

Spielberg hides the dinosaur specifically for just the right moment when it can awe us the most. The vision is built up and we anticipate the reveal, and that enhances the sensation when finally we see what we’ve been waiting for.

But I understand the confusion, in a general sense. I’m sure someone would say I’m just being contrarian or that I’m just hard to impress, but I fear there’s something much larger going on.

I think we live in an imagineless time.

I have watched most of my writerly peers over the last fifteen years turn themselves into small time pundits on social media, spending hours of every day staring at their phones. They don’t read like they used to. They don’t write like they used to.

Instead, all of their time is soaked up by their phone, by social media. They’re shackled in digital caves confusing digital shadows for the real life world they daily real lifely ignore to stare at their phone.

Children grow up with devices feeding them a constant stream of stimulation, of visual noise. The websites we use are all ugly, noisy, abominable landscapes wailing with a gale Deathly. Everyone listens to podcasts instead of music. Everyone watches youtubers or tiktokers speak into their frontfacing iphone camera rather than watch a movie.

Or, better yet, take a walk.

Hear the wind sing.

Feel the wind on your skin.

The biting cold.

See the leaves change colors, fall, desiccate and disappear, only to watch new ones sprout green into the air above you, into the canopy cradling the sky, embracing you.

For an imagination, you need idle time. Thoughtless time. You need quiet and the dark. You need isolation in between bouts of activity.

I remember dust and what it came to mean to me. Watching the dust drift through rays of light in the living room where I grew up. Watching the moon and the stars, smoking cigarettes on my roof while I longed for death, while I let imagination twist and turn and take hold of me, lifting me far away, drifting off into the everness, this neverness encasing me.

I drank too much. I prayed to no gods, to all gods, for death. I smoked cigarettes aesthetically rather than addictively. I fell in love with the gesture, the style, the visual imagery, the cinema of my mind watching me like I was not myself, like I belonged on a screen, on a page, and I allowed this overactive, hypersensitive imagination to consume, to rule me.

But what do our young artists have now?

They have access to every form of media ever placed online, yet most of what they consume is algorithmically tossed before them, like swine at a trough fattening their way to industrialized slaughter, some horror ritual that could only be orchestrated by the demiurge we’ve made of ourselves.

I find often that everything is an imitation of an imitation, that what’s described as bold and new is a rehash of something fifty years old, that these new exciting voices should have read a book or seen a movie or listened to a song from before their own birthyear because I am simply sorry that I have lived long and consumed art of all kinds mukbangly for decades.

People have been saying for decades more than I’ve been alive that there’s nothing new.

But perhaps these people never heard the Beatles or Fiona Apple or watched Akira Kurosawa or read a book covered in dust at the back of a shelf at a used bookstore.

Perhaps they’ve never felt the fire.

New Art

Matt Healy is about my age but I didn’t discover his music until 2013 when it struck me as something somehow new, or at least different.

I didn’t realize back then how this experience would become fleeting and even seemingly disappear from the world as I watch on, lived on. But I fear there is so little new and bold in art.

And perhaps picking Matt Healy’s the 1975 is a strange place to begin discussing this sort of thing, since many would likely call them nothing new or even nothing adventurous. And maybe the problem is that the 1975 speak directly to a specific age of person, which happens to be the age I am.

The kind of musical artists that echoed within me were largely one kind of thing or perhaps a mix of a few things. Rage Against the Machine combined rap and rock into a package to expound about politics. Radiohead were full on Brit Rock until someone handed Thom Yorke a laptop and he found the ghosts in the machine that would haunt him for the rest of his days, turning his lyrics increasingly abstract, leaving behind the meat and bone of those early albums. Though these two tendencies combined deliciously on In Rainbows, which maybe should have been their last album.

But the next generation of artists came up omnivorously consuming art and styles and genres like I did. Combining classical compositions with death metal felt as natural as breathing. Going to an acoustic show on a stage smaller than my living room one week and following it up with acid rock on a hill the next week followed by a violent metal moshpit the next week followed by an emo band bleeding their heart out on stage for thousands of we teenagers was the rhythm of our lives.

We read poetry and science fiction, fell in love with Harry Potter and Dostoevsky, had our minds blown by The Matrix and then Memento and Pi and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall and Rian Johnson’s Brick.

We devoured everything and everything. We soaked up Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Pan’s Labyrinth and Y tu Mama Tambien and on and on. We listened to French and Russian rap that someone first showed us as a joke but then became all too serious as we learned the lyrics to psychedelic bands singing in Norwegian or Icelandic bands singing in no language at all.

We consumed the world. We drowned ourselves in art from every continent, from every style, and it swirled within us, soaking down to the marrow, rewriting our lives, hotwiring our brains.

And we believed it would always be this way. The limitless nature of art, of expression. Every week, it felt like there was not only some new band to obsess over but an entirely new genre to fall inside, an entire culture opening to us through books and movies and especially music.

And this trend has continued, sure. We can now watch movies in a hundred languages without ever looking up from our phones.

But this is the other trick that’s now missing and, as it turns out, might be the most important bit:

Idle time.

Time especially being important. To memorize a song, you need to live with it. Live inside it. Listen to it on repeat, subvocalizing the lyrics in your childhood bedroom while you skip dinner or ignore your siblings, while you stare at the liner notes or your ceiling, while the world beats on, runs past us because we’ve encased ourselves in a moment, in a sliver of immovable time.

And when I heard the 1975 for the first time way back when I was however old I was back then, it didn’t so much feel like something completely new but like the inside of my head spilling out. This was a band that had wandered the same world as me, sucking up influences from anywhere and everywhere. Spongelike, we let it soak into us and what we spit back out seemed chaotic and obscene, schizophrenic in style and genre to those on the outside, but, to me, it all was one.

Seeing this expansive view of style and genre and aesthetics felt like coming home to me, though it was a home I never had a name for, that I’d never really seen expressed out in the open, in the wild. So to discover a band that wasn’t doing just one thing but trying to do everything all at once, to be all things, to deliver music in unwieldy and consumer unfriendly packaging felt so perfectly right to me.

That they became a gigantic success was certainly a surprise, but I think most of it comes down to Matt Healy specifically.

I can’t think of any frontmen younger than me. Can’t really think of any bands out there doing the thing thousands of people my age did when they were twenty. And perhaps this is because I’m old, but music seemed dominated by bands in the 2000s and 2010s but it now seems dominated by producers and solo singers.

Which is fine, I suppose. I like all that, too.

But I think there’s really something truly magical about a band on stage together.

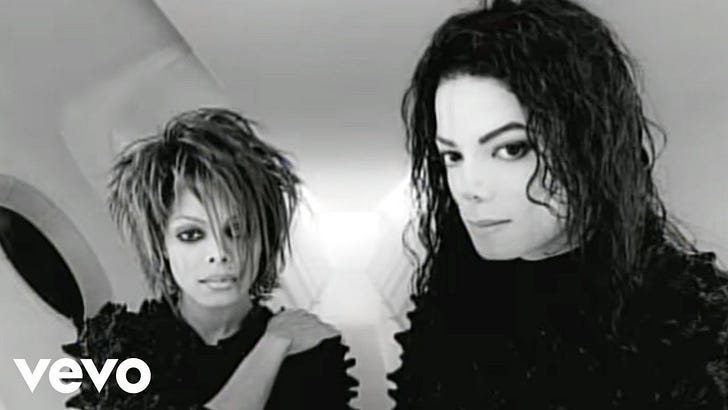

But even setting live performances aside, Healy has just a devastatingly flexible voice. He often sings quite beautifully, but he also often falls into this slurring cadence, or allows this harsh breath to enter his voice, reminding me of Michael Jackson in all the best ways.

michael jackson's voice

I want to talk about something very specific here, which is difficult when you open up the can of worms that is one of the most famous people to ever walk the earth.

There’s this violent edge to his voice, this sinister undercurrent. Even when he allows his voice to rise high and beautiful, he’ll rough it up a bit with this growling texture.

He’s a singer who draws inspiration from a broad spectrum and you can hear it in his voice. Michael Jackson, sure, but also Daryl Palumbo and Peter Gabriel and Connor Oberst and Jonsi. He talks about John Hughes and Seamus Heaney and Abbie Hoffman in the same breath when discussing his influences.

And, perhaps unsurprisingly, he too went through an Arthur Rimbaud phase.

I Like America and America Likes Me (2018)

The song begins softly, gently, easing us into an electrobeat. His voice is quiet and modulated, becoming a choir all at once, in a very Bon Iver way. There’s a purity to his singing, though. A clarity here. Then the beat kicks and this choir eases back and a rougher more forceful voice comes to the fore. Still modulated but he’s coming faster, his voice hitting notes prettily but at times also harshly and chaotically.

Then the beat dies and the choir returns and disappears when the beat kicks in again.

The song is repetitive both lyrically and musically, but this is done in the service of hooks and pop. The song wants you to dance. The beat almost demands it. The simplicity of the lyrics and the way they repeat invites you to shoutsing along with him when you’re standing in that sweaty crowd of thousands.

And we can discuss the lyrics a bit, though I don’t think there’s a lot that needs to be chewed on here. The lines are short and abrasive, reliant on this moment in time when violence and consumerism don’t so much battle for attention as much as they entwine and dominate digital spaces that have consumed our social lives.

You scroll past a hundred ads only to run into some violent tragedy like a school shooting or a mass shooting or some other massacre in the US or abroad. You learn about slavery in a country you never thought of between ads, between pictures of your nieces and your friend’s children before you scroll through a half hour of memes and then some polemic and then some ads.

Consider just the intro.

I'm scared of dying (Don't go)

Is that on fire?

Am I a liar? Ooh (I can't be quiet)

I'm scared of dying

No gun required, ooh

My skin is fire, it's so desired

And then the first verse.

Is that designer?

Is that on fire?

Am I a liar?

Oh, will this help me lay down?

My skin is fire, it's so desired

No gun required

Oh, will this help me lay down?

The repetitive nature should be a weakness. The lines are all Bukowski short and punchy. There’s little music inherent to the language here. Rather, it’s all quite unadorned.

The music relies entirely on Healy’s delivery, his performance, and you either sink with this song or soar with it.

The beat is infectious but is only ever one thing and it wants you only to dance, to sway your hips, to bounce from your knees, and even on first listen I already know this song, know this dance, feel it in my chest but especially my feet. My arms know what to do, how to sway, the shape of it all, of all things, and I bounce and bob, and my feet do exactly what the beat demands and I become thoughtless, swept up and consumed and controlled by this fucking beat that is both nothing and everything.

Over the top, raining down upon us, Healy’s vocals demand that we raise our faces and howl the words back into his lungs, that we become a single voice in a thousand mouths, that we all breathe as one, become one, our bodies marionetted by his beat, our voices conjured by his singular choir.

And I think since this song so relies on delivery, it’s worth examining a few performances.

Here we have something gentler, rawer, without the modulation and distraction. Here we have pianos instead of a drum machine. Pull back those digital ghosts and give us the human, the raw and the real. Without the modulation, we hear Healy’s voice take on different textures and go to different places, turning this dancebop into a ballad rushing breathlessly onward, with the only modulation being the Christina Aguilera inspired dance across notes when you think you want them to be held clean and straight and pure.

But these crooked notes, this slanted ballad fills our ears with a plaintive plea, giving a very specific depth to the emotions in the lyrics, which were so easy to brush over, to run past as we danced and screamed with a thousand tongues.

I'm scared of dying, it's fine

Oh, what's a fiver?

Being young in the city

Belief and saying something

Even the lyrics themselves seem distracted but rather than dance through this, rush past the sentiment, we’re slowed down and forced to consider these words.

What is this distraction and what does it mean to believe and say something? What should we say? What should we believe?

And perhaps that’s the real plea.

Believe in something, anything. Speak it. Say it with your whole chest.

Would you please listen?

Would you please listen?

We can see what's missing

When you bleed, say so we know

Being young in the city

Belief and saying something

We need to be heard. We all do, but perhaps especially millennials whose lives remain politically controlled by aging men so thoroughly disconnected from the life lived beyond their frame of reference. But there is no handing off to the next generation, as these dinosaurs cling to power, grip it as fiercely as they can with dementia hands.

But we hear it this time in his voice. The need. The plea. The desire. The hunger. The terror, the slippage of time, of all our silenced words, our ignored worlds.

And I have always been drawn to contrast, especially where rhythm and cadence and meter work in opposition or ironically against the content ever since I first read William Blake’s Chimney Sweeper3.

When my mother died I was very young,

And my father sold me while yet my tongue

Could scarcely cry " 'weep! 'weep! 'weep! 'weep!"

So your chimneys I sweep & in soot I sleep.

There's little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head

That curled like a lamb's back, was shaved, so I said,

"Hush, Tom! never mind it, for when your head's bare,

You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair."

And so he was quiet, & that very night,

As Tom was a-sleeping he had such a sight!

That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned, & Jack,

Were all of them locked up in coffins of black;

And by came an Angel who had a bright key,

And he opened the coffins & set them all free;

Then down a green plain, leaping, laughing they run,

And wash in a river and shine in the Sun.

Then naked & white, all their bags left behind,

They rise upon clouds, and sport in the wind.

And the Angel told Tom, if he'd be a good boy,

He'd have God for his father & never want joy.

And so Tom awoke; and we rose in the dark

And got with our bags & our brushes to work.

Though the morning was cold, Tom was happy & warm;

So if all do their duty, they need not fear harm.

And maybe I’m giving Healy too much credit here, but I get the same sensation from this poem and this song. This performance pulls something true out of the bop and makes us listen to it with new ears. While we danced chaotically while he pied pipered us along, he was singing of tragedy, of a bleak hellscape dominating our lives.

We’re as trapped as those poor chimney sweeps and just as deluded, though we think we’re warm and all together, all as one, singing and dancing to electro R&B.

But I think my favorite performance of this song is from their 2019 Lollapalooza set.

And, for me, it’s really the moments where Healy’s voice claws through the robotic modulation and breaks raw before us. The way these notes come screaming out of a rough and ravaged throat to shatter the autotuned illusion hits me in my own throat. And it feels as much like Kanye at his most emotional while also giving us something distinctly itself.

His voice, though pretty and bright, has this brimming rage to it, this coruscating violence swelling beneath. And watching it rise, hearing it echo in my head, in my teeth, gives yet another texture to these lyrics.

On the studio recording, he’s almost lulling us past the lyrics, demanding we look past them. On the acoustic live performance, we’re drawn to the tragedy of what he’s singing. Here, we’re given to the blistering anger over this tragedy, this oppressive digital ruin that has intoxicated us so wholly and completely that we can’t even take a shit without thumbing our phones.

The fire.

This is the fire burning bright and hot and scorching our bones and sublimating our lungs while blood steams away leaving us with this empty husk of a body.

To become the fire.

Be the fire.

Burn.

Shaman as Artist

And I think this is the shamanic ritual we have always wanted and needed. The frontman as shaman, the artist as revolution, the society as art. In order to become who and what we wish to be, we must first grapple with who and what we currently are.

And for all that someone may say about Matt Healy and the 1975, this path excites me. I cannot listen to this song and consider it simply another popsong, like he’s not at least attempting something new.

And, sure, yes, absolutely, what he’s mostly doing is stretching his arms octopuslike across influences and then pulling them all into his mouth to condense them into a diamond for mass consumption, but isn’t that what all great artists do?

Do we not all stand atop the shoulders of giants to see just a bit further, to make a slightly higher platform for the next great artist to see still farther out, past where our own aging eyes give out?

Free novels:

For those who have caught a glance at a history book this does indeed mean that Joseph Beuys was a soldier in the Nazi army

Named after my son’s namesake, incidentally

Perhaps I’ll write an explainer on this poem and see if people like this sort of thing. But to put it succinctly, the lullaby meter is used to deliver us a horrific reality.

Oh yes, idle time so missed, almost unacceptable these days but so missed. I think you are on to something, how can anything new be created without the idle time to think it through?

I've been reading Sebald. You have made me think of him. Then I found this article: Lerm Hayes, C.-M. (2007). “Post-War Germany and ‘Objective Chance’: W.G. Sebald, Joseph Beuys and Tacita Dean”. In L. Patt (Ed.), Searching for Sebald: Photography After W.G.Sebald. (pp. 412-439). Institute of Cultural Inquiry.