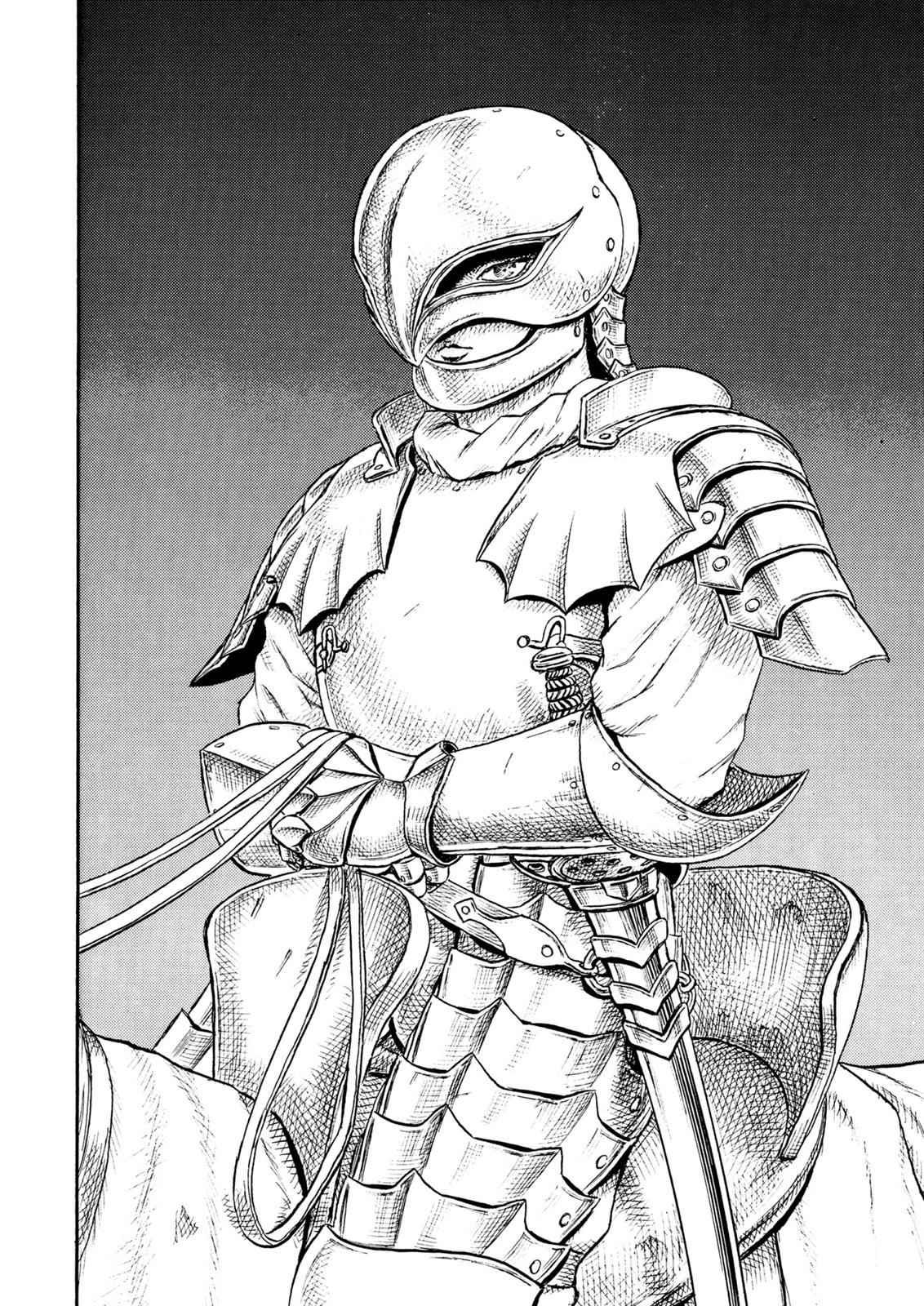

BERSERK: The Golden Age Arc (Chapters 9-17 and then 1-94)

or, we hoped and we lost and we hoped again

To view this whole essay, you’ll need to click over to the website. It went rather long so it no longer fits in an email.

Catch up:

Open Your Eye

I do not know how to begin this. I do not know how to write any of this. I thought I’d have this essay finished in April but after reading the 100+ chapters that make up The Golden Age Arc, I’ve been at a complete loss of what to say.

There are times in life when you encounter something that is simply too much. And perhaps it’s a problem with the project itself. Rather than split this into the Arcs, I should have written a review of every ten or twenty chapters, or something like that. Some other arbitrary delineation that would have made all of this composable.

There was a growing fear in me around Chapter 50 that I should break the Golden Age review into at least two essays, but I didn’t. Mostly out of laziness.

But now I sit on these 100 chapters, holding an entire lifetime of Guts, of love and brutality, of betrayal and glory, of Casca and Griffith and all the Band of the Hawks.

And the Godhand.

On top of all else, as some of you know, something sizeable began to change in my life in March and so simply sitting here and writing what amounts to a juiced up plot summary felt somehow dishonest or like a cheat.

A cheat for me and for you.

And so I sit here now in July after trying unsuccessfully to begin this for a few months, and I am still asking a fundamental question:

How does one begin?

a tiny bird

We have seen Guts fighting a lonely war against demons but now we leap backwards in time to Guts’ birth, and what a birth it is!

His mother died while pregnant with him and he was born from her corpse.

This is so edgy it almost feels like a joke and in any other hands, this is where you’d lose me. Or maybe the final place you’d lose me. This unrelenting bleakness, blackness. This world of absurd wretchedness.

This is where the Arc begins. Again, Berserk is telling you to quit if you’re not willing to swallow this whole. And maybe you should quit here if this bothers you, if this seems too dark. Because where we’re headed is pitchblack and dire.

But along the way, Miura shows us the otherside of all this horror and darkness.

A beauty. A simple kind. A precious, fragile gorgeousness all the more haunting because it is so fleeting on the page.

But it rests inside my chest now.

a thrumming in my chest

I must say, I did not expect any of this.

In general, I try not to be snobbish about different mediums. I have no great affection for comic books, having never read them until I was an adult. And perhaps this is why even the ones considered the best of all time just land into the pretty good category for me.

Rarely have I picked up a comic book that I’d consider literature. And I know that’s unfair and kind of childish of me, but I find that the storytelling and characterization in comic books is severely lacking. The genre, to me, feels like a bad case of arrested development. Middle aged men writing stories for teenagers with no real aim to do anything but entertain them.

It reminds me of emo bands pushing forty but writing songs about being in high school.

Which I do think is fine. All well and good. But I can only think of one comic book or manga that I’ve ever talked about the way I might talk about Dostoevsky or Le Guin.

And, no, it’s not Alan Moore’s Watchmen.

It’s Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind by Hayao Miyazaki.

One of those books I keep meaning to write about here, but, alas.

Instead I’m writing about Berserk and wondering if, perhaps, I’ve stumbled backwards into one of the most impressive artistic achievements produced during my lifetime.

And it has taken my whole lifetime for it to be published. The first issue was released when I was two years old. Miura completed his final chapter in 2021, before he died.

An entire lifetime—mine, for example—spent on a single work of art.

And while there’s still so much more left for me to read, I do feel as if I’m in the midst of a singular work.

I don’t know quite how to explain how exciting that is to me. I have wondered over the last few years if I’ve read all the best books. If I will ever encounter something that moves me, that changes me the way certain books and writers have. Have I grown too old to allow art to transform me, or have I simply run out of moveable art?

It’s an absurd notion, but also paralyzingly horrific. A terror that I don’t know how to reckon with.

And perhaps I won’t have to. Because, for now, there’s Berserk. And though there are 250 more chapters to read, I feel this thrumming.

Do you hear it?

When you look upon Guts looking upon Griffith, do you feel it in your bones, in your teeth?

a brutality

Guts is raised by a band of mercenaries. He is despised but kept around and so he is raised without love, but he sees how affection comes from glory, from ability.

These are rough, vile men doing rough vile work. The work of killing. Of butchery and brutality. There is little love in them, and we see, in a way, a Hobbesian world made real. Brutal men living brutal lives where the biggest, baddest brute leads the others.

And so from a young age, he begins practicing with a sword. It’s a sword for an adult and far too large and too heavy but he wields it all the same.

Gambino is his adopted father, of sorts. His lover picked up the infant Guts was and cared for him. He’s the leader of this mercenary band and he allows Guts to hang around with them. Eventually, Gambino gets hurt, his lover dies, and he is no longer able to fight and so he spends his time drinking instead. One of his mercenaries pays Gambino so that he can rape Guts.

Gambino takes the money.

And we witness Guts, still a child, raped by a man. A large terrifying man made of iron and violence.

We see Guts lunge for that too-big sword to protect himself. We see all choice taken from Guts as he is used.

Gambino took the money.

Gambino. If Guts had a father or mentor or caretaker, it was Gambino.

But this is the world Guts was born to.

Later, Guts, still little more than a child, joins the fighting in the mercenary band, using his too-large sword. In one such battle, he finds and kills his rapist, who is one of his comrades. Later still, he inadvertently kills Gambino and is then chased out of the mercenary group. They hunt him for a time, hoping to kill the ungrateful child who killed his own father.

And even after finding out what Gambino did to him, how he sold him, he is torn by regret and pain. For though Gambino didn’t love him the way a child needs, he was a father. A terrible, miserable, evil father, but a father, nonetheless.

Crimes against children, especially those perpetrated by their parents, absolutely rot us from within. Even hearing about it. Even knowing it exists—it’s enough to make a body combust.

For years, Guts lives a somewhat nomadic life as a mercenary. And he is a terror on the battlefield, seemingly invincible and unbeatable, still wielding a gigantic sword.

And then he meets Griffith.

a weight in my heart

It’s been a strange and difficult year for me. But I’ve been thinking a lot about fatherhood and childhood. About what it means to do any of this.

I woke up this morning at 6am to do chess lessons with my son. It’s sadly supplanted my previous habit of waking up at 5am to write and so now finding the time to write is more difficult. But he’s awake and he wants to be with me.

What do my words matter when weighed against my son?

And I consider the fact that he is a boy growing up. And I fear for him.

For I have known other little boys.

I once was one.

And I remember how the world battered me and the crushing despair I felt when I was perhaps too young to experience such things. And I see a child who is like a son to me and I have watched how life squeezes him. How it threatens to crush him. See the ways he holds his head up, holds himself together while his world crashes down around him.

And I would weep for this child if I thought it would do any good. But instead I do what I can. I show him love. I show him that he has a family. That we are his family. That we love him. That we will always love him.

That he is a brother to my sons and a son to me.

And I hope that it will be enough.

And I hope.

I hope.

Hope.

a way

Such fragile birds, these words. Such savage gods.

The Tao asks us to be. And I try to be.

Demonstrate a path.

A way in life.

Mine has been crooked and broken and tangled but it has been mine. I would not recommend someone follow the track I beat through life but I hope that my sons, each of them, all of them, will be able to learn strength and resilience from me. Because for all my many faults and the ways I’ve collapsed, I’m still here.

I live. Sometimes accidentally, sometimes despite everything, but life goes on and so must we.

So must we.

a light in darkness

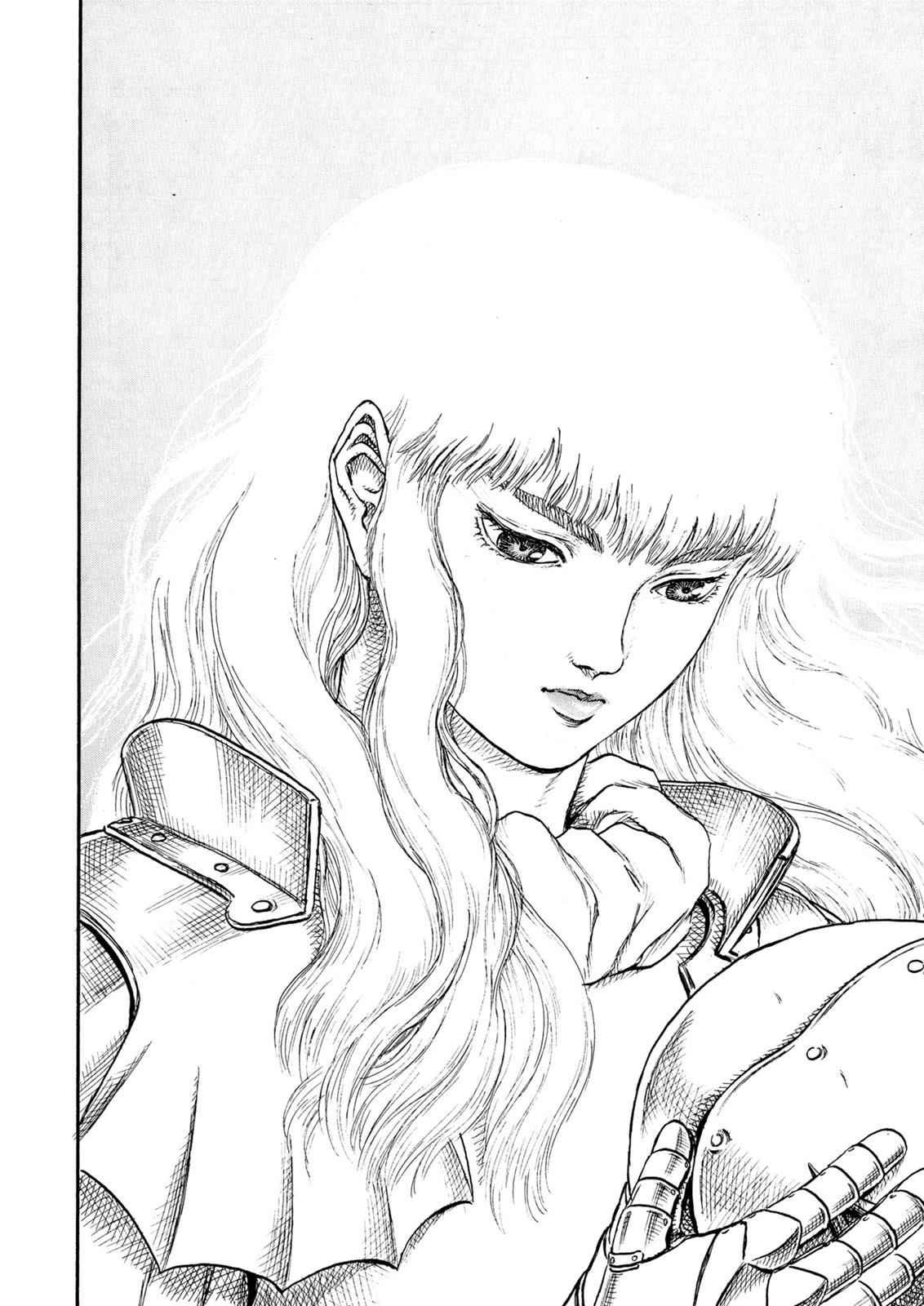

Griffith shines so bright. He is beautiful but he is also powerful. Unbeatable. Even Guts cannot beat him, yet Griffith sees in Guts the first person in life who may be his equal. Who he can share his life with.

Casca, Griffith’s commander in the Band of the Hawks and the only woman in the mercenary band, quickly hates Guts. And we see, quite clearly, quite early, that this is jealousy. And not jealousy over Guts’ ability as a fighter, but because he is a rival for Griffith’s affection.

And the relationship between Guts and Griffith may not exactly be romantic, but if you turn the dial just one notch over, you have a love story between these two men. Two men from broken pasts who have been brutalized by life.

One turned all this into light. Into a path to glory and out of misery.

The other turned it into violence only.

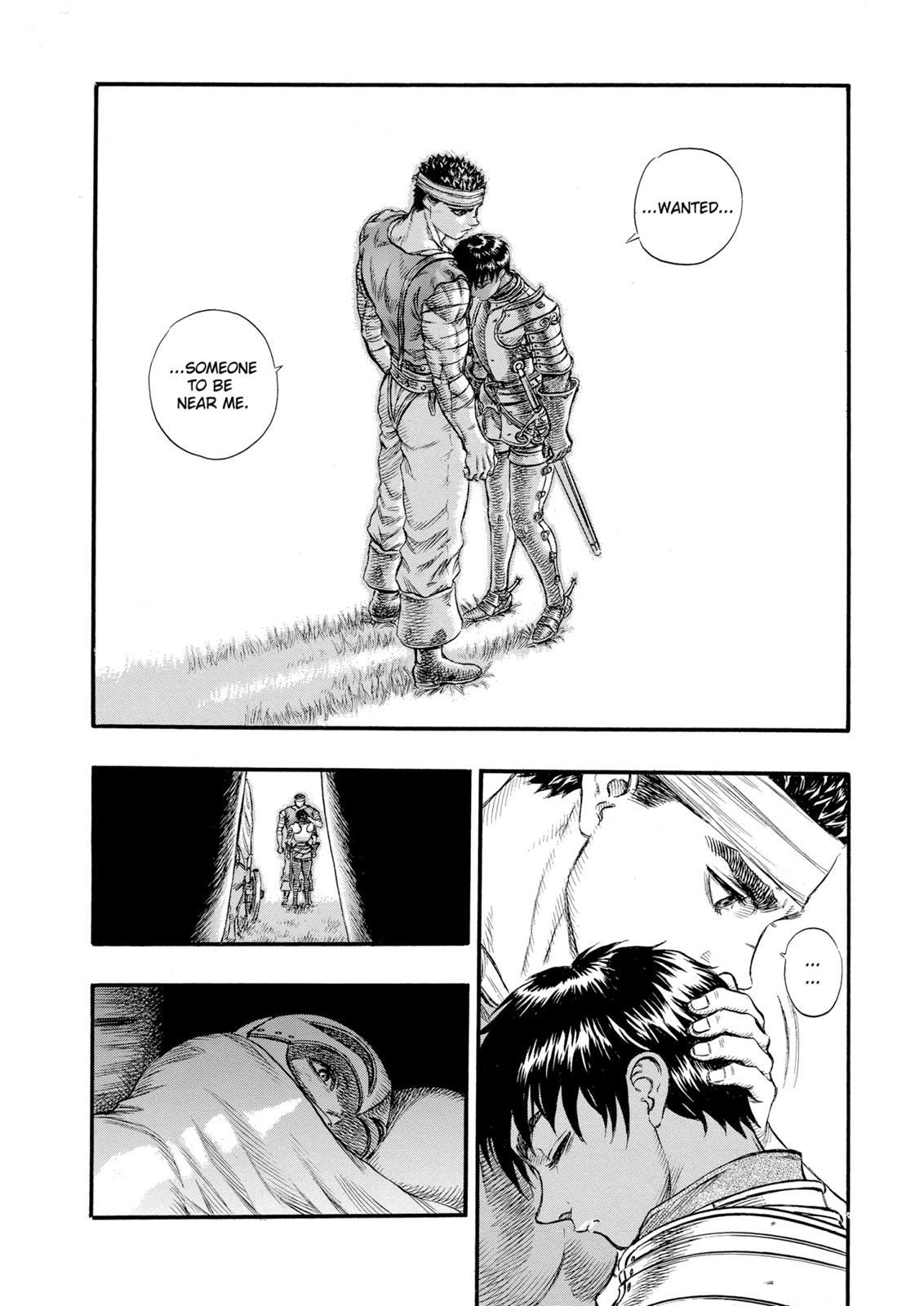

But when Guts meets Griffith, when he spends the three years that The Golden Age Arc is named for with the Band of the Hawks, when he looks upon his comrades and finds himself beloved, amongst friends, we begin to watch how a ravished man may heal.

It is so simple.

So delicate.

The profound power of friendship.

The love we share so freely. The love we share without even knowing. The love between men who become closer than brothers. Men who rely on each other, who exist because of one another.

It’s a potent tonic, intoxicating in its acuity. To see someone absolutely shattered by the life thrust upon him and then to watch as he slowly heals. We witnessed how Guts became a violent monster who trusted no one and hated everyone. We were there when he was raped as a boy, when he was despised, when all he wanted was for Gambino, his father, to look upon him with kindness.

Give him just one single word of kindness.

Any word.

And then we see this damaged monster slowly become a man through the incremental accretion of affection, of love.

We are not lost.

It struck me powerfully here as a man stumbling towards forty. I cannot imagine quite what this story may have meant to me had I picked it up when I was twelve or fifteen or even twenty.

We are not lost.

We can be healed. Saved from ourselves. From the life we’ve lived and the choices we’ve made. We can become someone new. We can heal ourselves.

But we cannot do it alone.

a touch

Remember the dirt beneath your fingernails. Remember the words she said to you that made you vomit out the nightmares. Remember touch. The way it felt. The way it hurt. The way it soothed.

Remember your body. Remember that we make it with every choice. It does not belong to us and we do not belong to it.

We are it.

We are our bodies.

Not our thoughts or dreams, or at least not those alone.

Remember the desire to be understood.

Perhaps the artists hunger for this above all others and so we find our way to music or dance or paintings or these mad scribblings that have consumed me. The need to be understood.

To feel the touch of another. To recognize the other in the self and the self in the other. To discover that you are not alone. That you are part of a tradition, a vast chain of people who have been where you’ve been, who have suffered as you’ve suffered, who have hoped and dreamt and tried, desperately, fiercely, to make a better world or to simply make themselves understood.

Screaming banshee free into the vast emptiness, tearing at this sprawling tapestry draped over humanity.

Remember that need, that vibration in your skull, that blinding spike of pain between your eyes. Remember the dirt beneath your fingernails. The sand and salt in your mouth when you nearly drowned off the coast of California when you were thirteen because you went too far out, chasing that wondrous ecstatic sensation of emptiness, of nothingness, way out there beyond the coast, past where you heard or saw anyone, where there was only you and those savage ancient gods of water and sky and the fire burning in your chest as they held you under and your breath scorched until you nearly gasped in a lungful of ocean, only to emerge and take that first breath, only for the ocean to spit you back out into humanity, into civilization, into the rest of your life.

a healing

I have known many broken people in my life. Probably you have too. They often walk among us like all of us, shattering within while they smile and laugh and carry on.

I have tried to heal so many of them. I do not know if I’ve ever been who these people needed or if I gave them what they needed but I did try. I continue to try. And even when these efforts have been rejected or ignored, I have still tried.

And perhaps it’s my own brokenness that led me to these people. A group of shattered hearts shambling along together, holding one another up, surviving for and because of one another. But I was fortunate enough to find a way through it all and become someone who can stand.

We need each other. We belong to one another. And if you, dear reader, sometimes find my political commitments offputting, know that most of them come from this simple belief inside of me.

We belong to one another.

It is so little.

It is so much.

So delicate yet sturdy enough to hold up civilization.

And it is this that I most hope to teach to my sons, to impart to all those who know me, who have known me, who will someday know me.

I teach my sons to be kind. Or try.

Because that’s my deepest hope for them. I would rather them be kind than anything else. And I hope that the people in my life will remember me kindly when I’m gone.

a golden dream

The Band of the Hawks is a mercenary band, which means they kill for a living. Midland, the setting of Berserk, has been at war for a century and so mercenary bands scour the land fighting and pillaging for pay. A land controlled by brutal, hard men with a taste for violence.

The Band of the Hawks has become legendary because they always win, but they are also shown as a contrast to the other mercenaries. We have seen the mercenaries Guts grew up with. Savage men only fit for savage deeds. We see the knights of Midland and the other mercenaries in much the same way.

But the Hawks have a gentle beauty to them. Many of them come from hopeless backgrounds. Griffith pulled them from the dirt and the mud and the shattered world to become a member in a family. Witness the bonds formed between all these outcasts, these people who were once without hope, without futures, but stitched together by Griffith. We see how they feel a stake in the Hawks, how they have tied its identity to themselves and their identity to it.

And at the center is Griffith. He is worshipped by his army. They see him as almost godlike in his ability but they also view him as a friend. As one of them.

He becomes an example and an emblem and a mascot of sorts for who and what they can be together.

And so when Griffith is raised to the peerage by the king of Midland after ending the 100 years of war, he takes all the Band of the Hawks with him. They are all raised and given land, titles.

All as one. All together.

Griffith brought them there through violence and an unending, insatiable ambition. We and Guts alone witness the lengths he goes to rise. He sells his body. He assassinates children.

He is a bright shining wonder, but he is pitiless and brutal and cunning.

He is the most dangerous man in Midland and he has been raised to the nobility, rising from the gutters with no name.

And then, shockingly, Guts tells him that he must go. That he must leave the Band of the Hawks.

That he must leave Griffith.

And Griffith the invincible shatters.

a sickened heart

Slowly, Guts and Casca fall in love. It is a strange passion born from pain and desire and rotting hope. They both love Griffith. They both belong to Griffith. Their hearts especially.

This binds them together closer than blood.

It may seem strange but I recognize it in my own life. I cannot explain it further than that. This somewhat diseased affection shared for someone that becomes a knotted cord binding the two of you together and separates you somewhat from the original object of affection.

Perhaps it stems from the lack of fulfilment. Desire unfulfilled warps and your desire shifts and the two of you find a new kind of love through this fraught and trembling connection.

a love, deathly

Guts and Griffith have fought demons and impossible beings together. One of them, Nosferatu Zodd, tells Guts that he will die for Griffith’s ambition, because of their friendship. There is magic and might between them. Death and glory. Hope and survival.

There is love.

A sharp, terrifying love. One that Griffith believes cannot be severed.

You belong to me, he says to Guts.

Rather than terrify Guts or send him reeling away, it intoxicates. A feral desire, here. Bestial and erotic but never consummated.

But we feel it

Guts and Griffith feel it.

This thing between them.

This love.

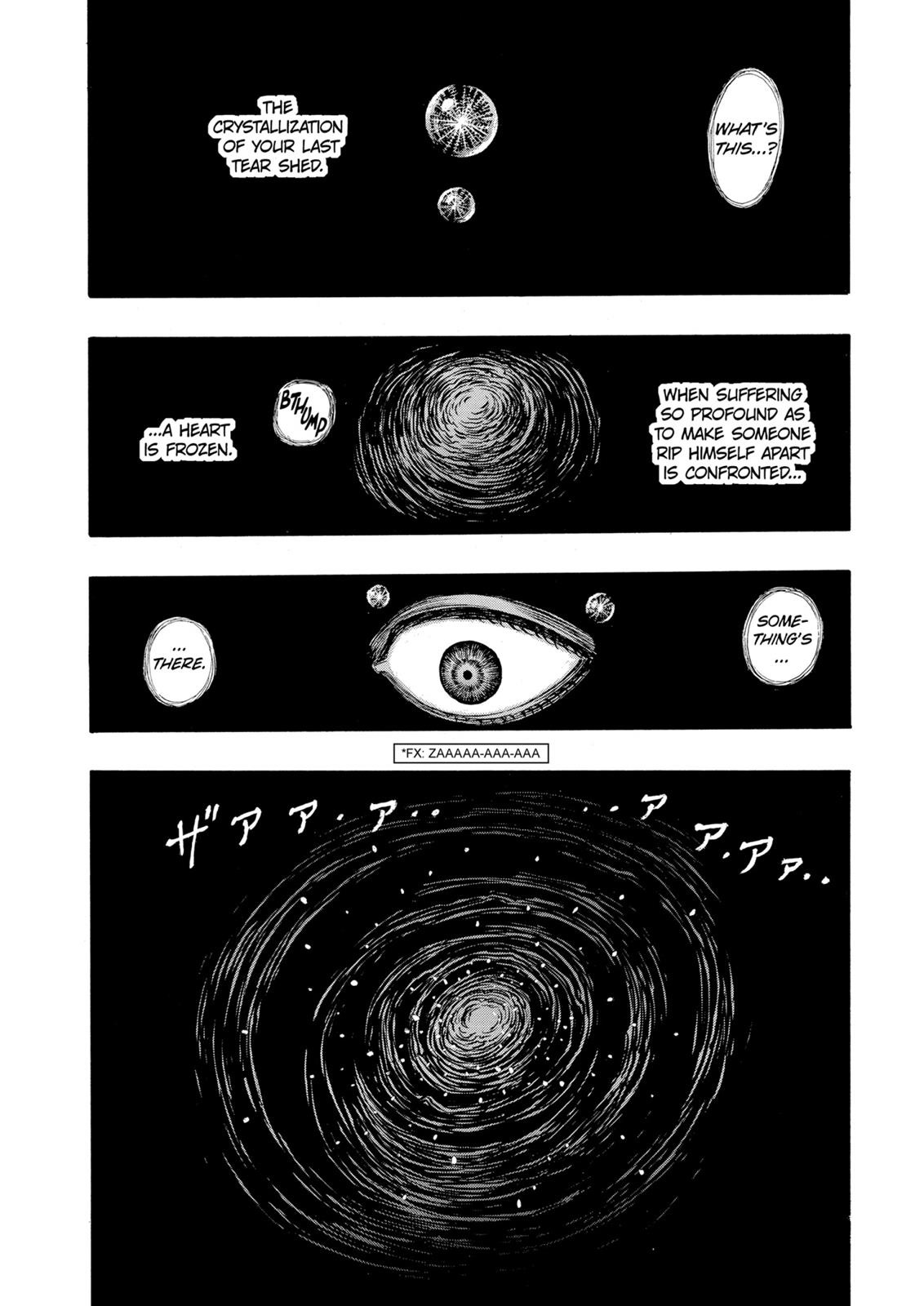

Griffith, born to nothing, rose from the dust and the dirt and the mud and the shit. His ambition never outstripping his ability for his ability grew exponentially. He discovered a Behelit when he was young. A strange pendant with several faces. Only he and Guts know that he has it.

Everything Griffith has desired in life has become his. And what he desires is a kingdom of his own.

And he has found a way to get there. He is at the cusp of achieving everything he hoped for in life.

And then Guts says that he must leave.

Guts believes he must leave to discover himself, to find his own, individual dream. To become his own person, separate from Griffith and Griffith’s dreams.

It is, Guts believes, the only way he can truly be friends with Griffith. Because Griffith deserves a true equal, Guts must become what Griffith is in order to become a true friend.

It is for love that he leaves.

Guts wants to deserve Griffith.

And Guts has no dream. No ambition.

He has spent his life surviving one battle after the next without much thought for his own desires. Even his love for Casca is one he believes cannot be fulfilled because he has been caught in the wake of Griffith’s dream.

To be worthy of either of them, of both of them, he must selfactualize, to put it a certain way. He must become a man who knows himself and who makes his own path, his own future.

He leaves Griffith out of love and desire for him.

But Griffith feels only terror and dread at the loss of Guts.

He tells Guts that he won his service in a duel and so Guts must defeat him in order to leave.

It is a petulant, childish way. But it is the first time we see Griffith in pain and out of control.

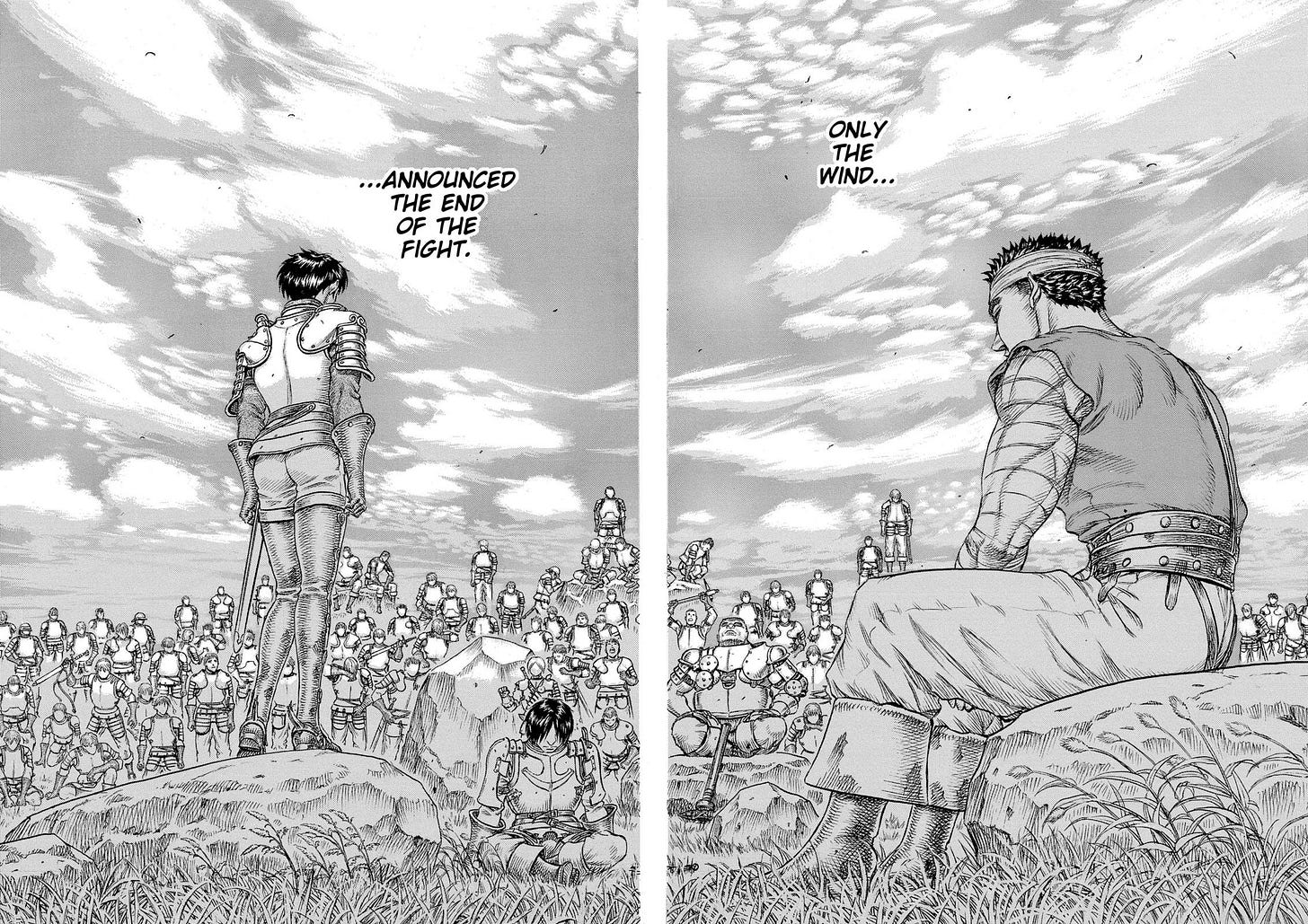

Guts wins the duel, shocking everyone, for Griffith has never been defeated in battle, and Guts leaves. He leaves Griffith and the Hawks stunned and lost, unable to understand why, at the apex of all they fought for, Guts would turn his back and walk away, alone, into the vast nothingness waiting for him.

Griffith’s life is a glass ball. Perfectly round and perfectly designed. He made it with his own hands. It took him his whole life but he has made it and it’s his. It took everything he had.

That night, in a fit of madness and despair, at the edge of all he desires, all he has spent his life thriving for, Griffith shatters it against the stone floor.

He seduces the king’s daughter. He is caught. He is thrown in a hole and tortured for a year.

He loses the Behelit.

Meanwhile, the Band of the Hawks is set up for a massacre that they narrowly escape. And only because of Casca’s leadership.

a breath

Hamartia.

Hamartia.

To miss the mark. To err.

This is the Greek and fancy term for the tragic flaw that afflicted so many Greek heroes. In essence, it describes a characteristic that makes someone great but that also causes them to fall.

Griffith’s ambition. Guts’ longing for acceptance.

These traits drive the story. They drive both men onward. Griffith’s ambition brings all of these disparate people together, uniting them in a single cause. Guts found acceptance only through his ability to kill and so he has become unequaled on the battlefield. Along the way, he made friends. A family. And they did not love him because he could kill.

They loved him for who he was.

But Guts did not understand what this all meant.

He believed he needed to change to be worthy of this love. Believed he needed to grow, becoming a new man.

Do you hear that?

My ears ring and my vision funnels.

All that we are, all that we believe we must be, all the ways we must change to be loved. But, all along, love was there.

Open armed, waiting for us to come out of ourselves, to stop being so selfabsorbed.

Open your eyes.

I can hear it.

Do you hear it?

Pathos. Ethos. Thanatos.

More Greek. More words to define this story, to try to corral it into a cage where I can make sense of it, where I can try to illustrate to you what Berserk is doing and why it’s worth experiencing, why it’s worth all these words.

Ethos, the drive for life.

Thanatos, the drive for death.

And Pathos, our emotions. The appeal to our emotions. This derives from the violent confluence of ethos and thanatos in Berserk.

Guts’ indomitable spirit, his forever battle for life, to survive. Yet the war he wages is one that constantly brings him to the edge of death. It’s a suicidal war. A savage battle ripping himself apart.

Yet on he fights.

Fights for life.

Your heart looks like a fist wrapped in blood and I feel that fist in my chest rising to my throat and choking me.

And then one final word of Greek: catharsis.

a very brief intermission

From here on out, the spoilers become quite severe for a moment that is unlike any other I’ve encountered in literature. If you’d prefer to experience what happens next for yourself—and I do fiercely recommend it—may as well close out of this for now.

It will be here whenever you catch up.

a tree

Tethered to the sky.

That’s how I felt.

Tethered to the sky but bound to the earth.

A child full of big dreams and a head full of big ideas who believed the only way to become himself was to escape, to run far away, to experience worlds and lives alone. To run from the life I had known, the people I had known, my friends and family.

Escape the shackless of everyone who had ever loved me.

Staring at the moon for years. My lungs full of smoke watching the open skies, the clouds marching over my backyard, marshalling my thoughts and desires off into other worlds. Brooding and hoping and dreaming and wallowing in my unhappiness.

In my words.

These savage gods. These brittle birds.

I stood there beneath a massive ash tree that had to be chopped down a few weeks ago because of the disease murdering it from within. Seeing the stump, running my hand over the wood—a tremendous sense of loss. As if the final fragments of that unhappy dreamer was also gone.

And returning home taught me much. I never planned on living in Minnesota again. Never planned to even spend much time in America again. But coming home revealed much of life to me just as wandering far afield taught me much. For you can never outrun yourself or the place you’re from. The dirt of the land of your birth remains in you no matter where you go or how long you spend there.

The shapes my lips and tongues make to form words, the ways my eyes see the world, the way my body responds to life—the land of my home gave these to me.

Minnesota.

America.

No matter where I went or who I was there, I was always from Minnesota, from America.

The land built me. But the people of this land nurtured me. They created me.

All of you. All of you who have known me for so long.

I am because of you.

You shaped me. You saved me.

You gave me life.

all along, all alone, please come home

After a year away, Guts meets the Skull Knight, a skeletal knight on a terrible steed. A warrior as powerful and horrible as Nosferatu Zodd. Because of what he says, Guts runs to find the Band of the Hawks and what happened to them.

He finds them in shambles, about to be massacred, and he fights with them and reunites with Casca and discovers that Griffith was betrayed by the king of Midland, that he resides in the dungeon being tortured.

And here we see what Guts could not see. We watch it strike him like a hammer to the throat.

He did not find himself by leaving.

He lost himself. Lost all that mattered.

Our desire to become ravages who we are. We cannot see ourselves. We cannot feel ourselves. We stand at the edge of the earth, an endless shore, and stare out into the everness of eternal oceans, and we consider something out there, beyond us, the true and the real while we are caught in this state of incubation.

But in leaving our home behind, in leaving our friends and loves behind, we only sever ourselves from who and what we are. We were not dreaming.

We were living.

This is life. The muddy, murky nothingness of everyday.

My dry hands on my face scrubbing the flesh raw.

We must learn to be.

We must find contentment with ourselves.

And we must carry on, for this is life.

Guts left because he believed it would make him a better friend, more capable of love.

And in returning, he found all that love, all that he needed, was broken, severed, shattered.

Could he have saved it? Could he have kept it from dying?

Did it all crumble to dust because we left?

I have asked myself this question many times about certain people I know. People who seem so lost. People who I have loved for most of my life. While I was looking the other way, their lives began to dissolve.

And I do not know how to forgive myself for not being there.

Guts finds Casca, alive, though broken and near out of hope, and she finds him and they fall into one another and consummate their love for the first time. And we see how this is the first sexual touch Guts has had since he was raped as a child and we witness as this crashes into him and nearly kills him and we witness Casca comfort him and we witness how two broken people can heal one another.

How two become themselves because of one another.

Touch.

A hand on my chest. A hand in mine. The softness of your cheek. Your savage embrace. My heart splintering to pieces as I weep from this inexplicable moment of being. Of understanding. Of discovering myself through you.

And I see my wife and the broken misery I once was and the way hope burst like a sun into my life.

Through a mix of luck and daring and wretched violence, they break into Midland’s capital and rescue Griffith.

But when they discover him—

It is only Guts who goes to him. He keeps the rest away. Will not allow them to witness what’s been done to Griffith.

And without saying it, we hear it echoing in our heads and our chests because of the way we know it thrums through Guts: This is because you left.

And he’s brought back to his childhood, to all the darkness and dread, to the fear and horror, to the violence. The crushing weight of life suffocating him, raping him. The choices he made and those he didn’t all conspiring to crush hope out of him.

And Griffith is a horror.

Tongueless, he cannot speak. His tendons have been severed so he cannot stand or walk or hold anything. His head is encased in the hawk helmet he once wore so proudly on the battlefield.

Griffith who was invincible, now an invalid. Unable to speak or care for himself. Unable to stand or fight.

These two men meeting again, with all the hope and love between them, hit me like a brick.

This page nearly broke me. The way Guts clings to him. The way Griffith puts his hands on Guts’, the way he cannot speak. Mountains of love and shattering hope. We see the anguish and the way Guts begging for an unspeakable forgiveness.

I left you.

I didn’t know. I couldn’t know.

If I could, I would take it all back.

I would never have left. Never have let you go.

Because of those we leave behind. Because of all that’s between us and the ones we love, the ones we leave, the ones who leave us.

I hear his voice sometimes still. I have stood witness to him shattering for twenty years and I didn’t understand my part in all this. My part in his life. Didn’t know what I was meant to do, what I could have done. Could we have escaped it all, escaped so much, had I made a few different choices?

Would you be happy today?

Would all of you?

When we met, we were so young. So bright and shining.

I see your faces. I see your smile and hear your laughter. Those little boys we were running through neighborhoods. Full of hope. Full of life. All existence before us, thrumming with desire, with passion, with endless possibilities.

And I fear that I’ve failed you, my failing friends, succumbing to diseases of despair.

My brother—

There are words that choke inside me. Words that capsize me.

Moments in time, crystalline and capacious, where I could have stretched out my hand and taken yours and maybe we could have walked away together, closer than blood, closer than love, bound together through the years.

What I would not give to heal you. All of you.

We see the weight of all of this collapse onto Guts and we watch him stagger on like Atlas carrying the world.

And as they escape, carving a violent hole away, we see Griffith observe. Silent and shattered, he sees in an instant the love between Casca and Guts. We see through his eyes how the remnants of the Band of the Hawks has remained together as one, beautiful and bold and barely holding on.

We see him understand all that he has lost. All that he will never have again.

And they run from the armies of Midland

Until they hit the Eclipse.

There is no way to really describe this in a satisfying way. The pages that unfold before you once the Eclipse happens is unlike anything I’ve experienced in a book or even movie. The closest may be certain moments in Steven Erikson’s Malazan Book of the Fallen or maybe certain moments of certain Final Fantasy games. It’s so tremendously large and evocative and wild that it defies any real attempts to translate it to sentences here.

So if you’re reading this but still haven’t read Berserk, you owe it to yourself to stop here and pick up the manga.

Griffith finds the Behelit again and his blood transforms it.

And the world transforms.

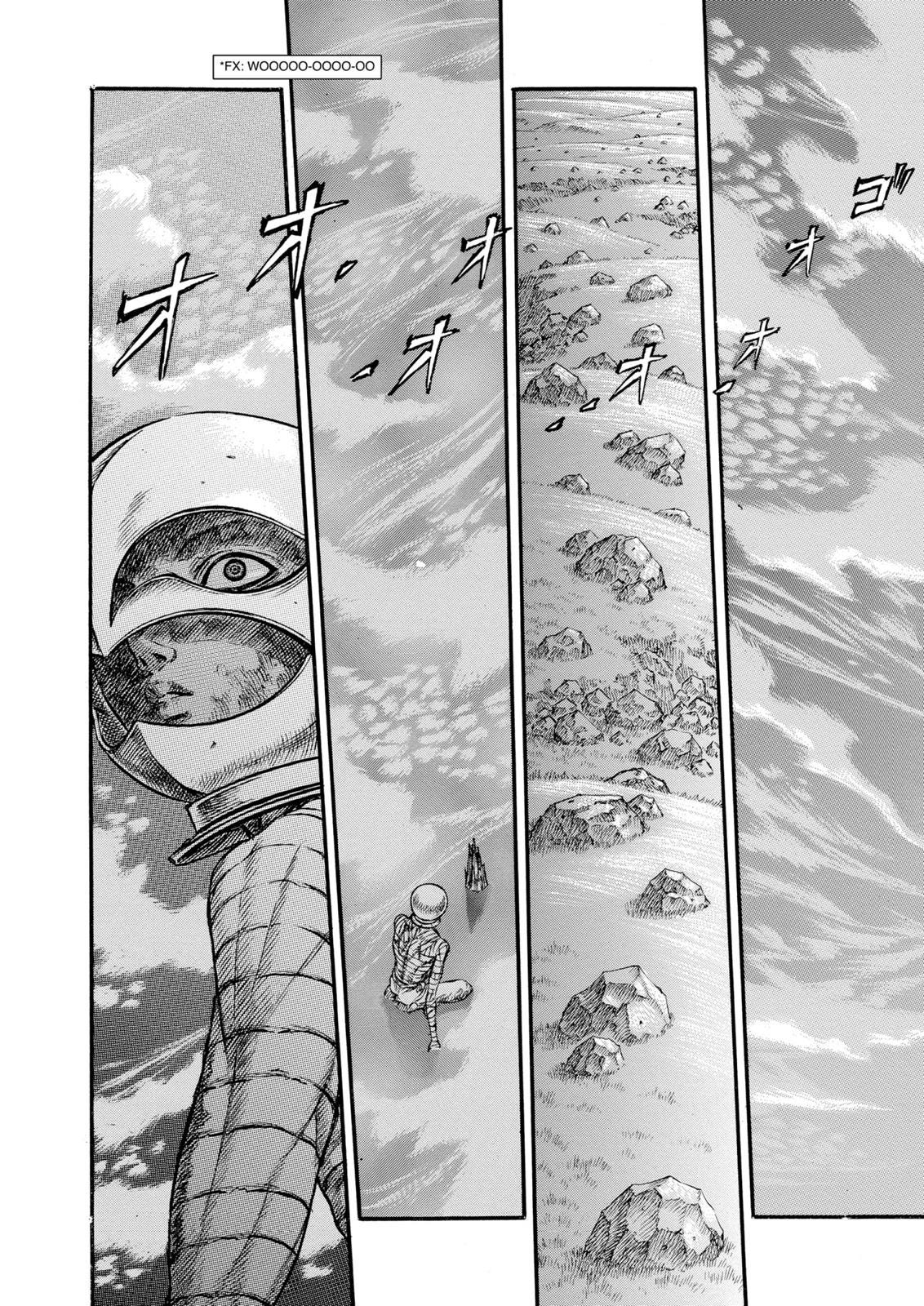

A convergence of the physical and spiritual worlds and the emergence of the Godhand.

The four demons we saw at the end of the Black Swordsman Arc. They reveal to Griffith that he has been chosen as their fifth member but only if he sacrifices everything he loves.

And Griffith accepts.

And perhaps most striking of all in this moment is that we immediately understand.

We understand all that he’s lost and so we understand what he hopes to gain.

Because, truly, what the Godhand is offering him is power. All his ambitions fulfilled. But perhaps even more than that they offer him an end to pain.

And pain is the recurring theme here. The importance of pain, of suffering, and how they make us human. They define who and what we are.

We are so much more than meat and blood. We are so much more than our thoughts and desires, than our hopes and dreams. We are even more than our choices.

And this is why I cannot help but be believe in an embodied world.

I am not a soul or a mind tied to a body.

I am a body.

I am my pain and torment and my sufferings.

But these pains are not alone in defining me. I am also my pleasures and my laughter and my smile defines my face as much as my scowl and my choices and follies are carved into my flesh, into my broken scarred nose and the permanent slice in my eyebrow and the chickenpox scar on my forehead and the scar on my wrist and torso from surgeries and I am my broken toes and my crooked fingers and my crossbite.

Who I am and what I’ve done are written on my body as a map.

A map of self.

And this is precisely what Griffith wants to give up.

The freedom to escape yourself. To escape the pain. To escape this mortal body. The torture and heartache and abject horror of diseased and dissolving dreams and hopes.

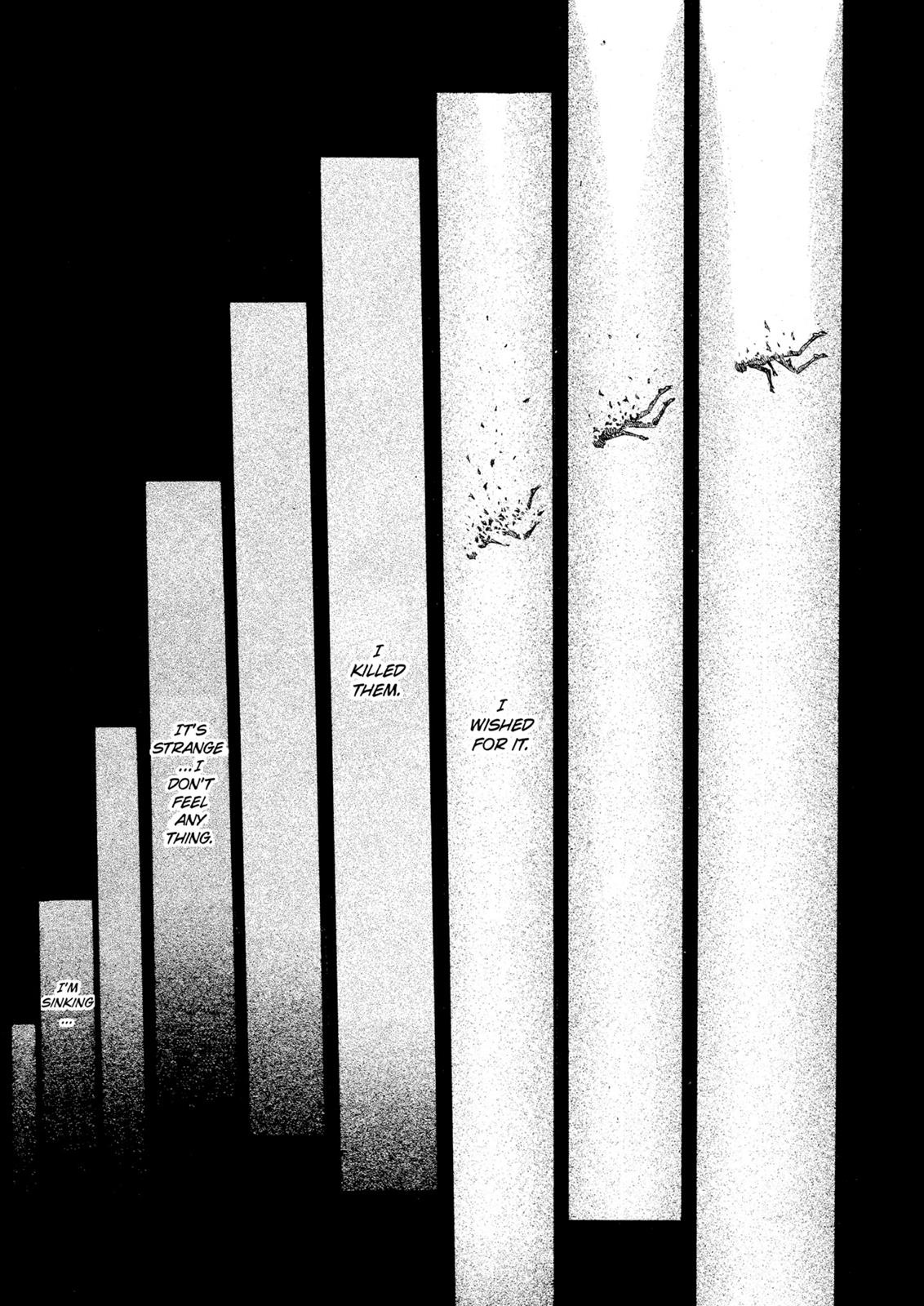

Thus and so, all the Hawks are branded with the sigil of sacrifice by the Godhand, which we recognize as the bleeding brand on Guts’ neck from the Black Swordsman Arc. This sigil that calls demons to Guts, keeping him in a state of permanent movement.

Once branded, the Godhands’ demons—other people who gained power by sacrificing their loved ones—massacre the Band of the Hawks.

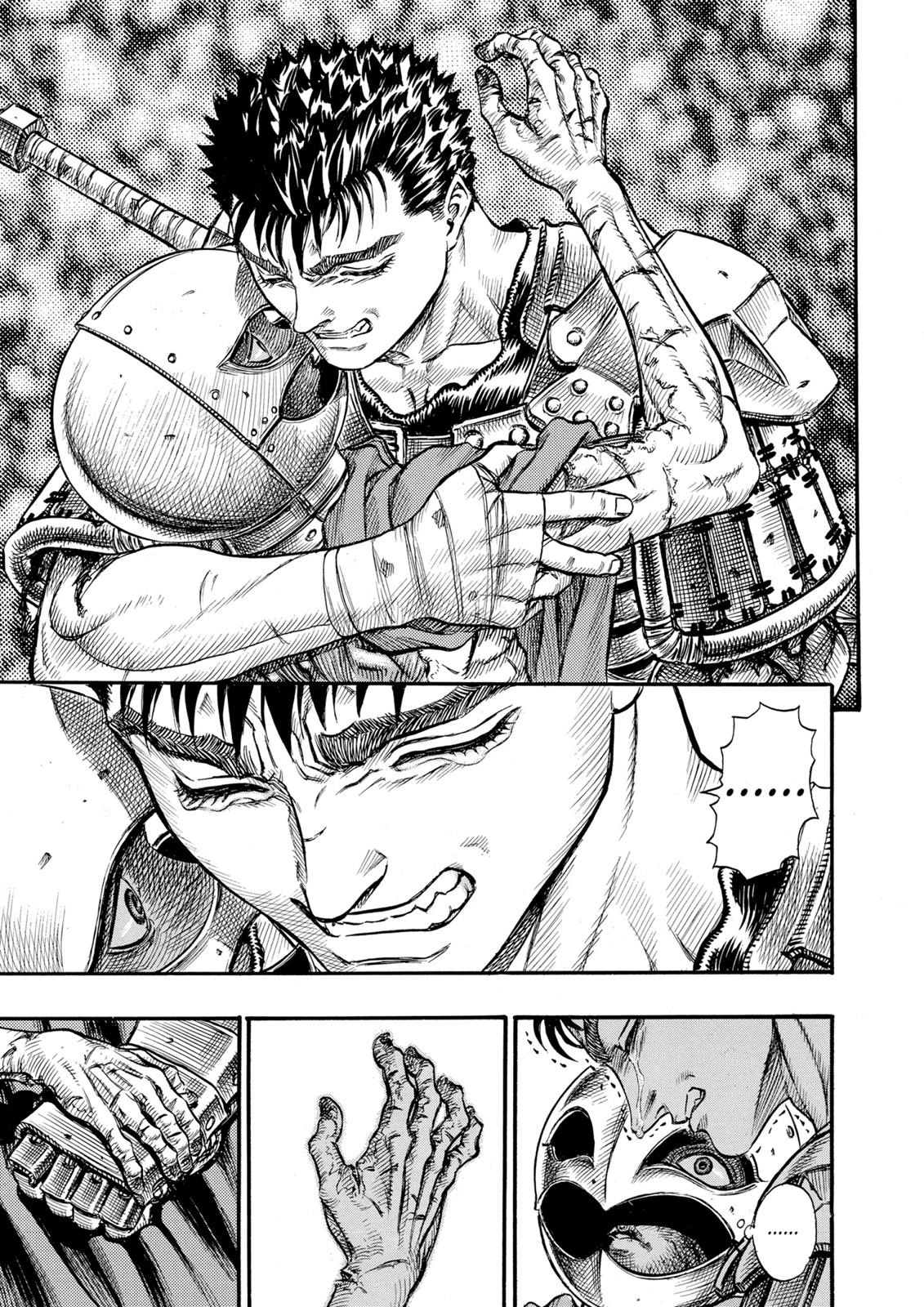

But Guts fights.

Impossibly, he fights on.

And he sees what Griffith has become.

The powerful, horrible demon rises from the broken shattered carcass as Femto. A new demon still wearing Griffith’s hawk helm.

Femto then grabs Casca, ripping her clothes away. We have witnessed Casca’s love for Griffith and her desire for him. We know she’s devoted much of her life to Griffith. He freed her and she bound herself to him, swore her life to his.

This was one of the great chasms between Guts and Casca for so long.

They loved one another, but could they love one another with the spectre of their love for Griffith haunting them?

Guts understands what’s about to happen. He screams and begs, becoming bestial and deranged. Begging Griffith, his friend, the man who gave him a life, to let her go.

Just a few chapters ago, Guts and Casca were finally able to love one another. To accept what they mean to one another. How much they mean to one another. How much they need one another.

A terrifying, blessed need.

Please, do not do this.

Please.

But Griffith is dead. Gone.

Griffith was human.

Femto rapes Casca in front of Guts while Guts is held captive by a horde of demons.

It is horrifying to witness and Miura is unrelenting. If you’ve ever seen Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible, you’re in the same arena of how this rape plays out.

Guts fights to break free, severing his own arm and losing an eye in the process, in one of the most brutal scenes I’ve ever witnessed, right up there with 127 Hours. And Miura creates this visceral horror with only black ink and paper. And it is a wonder to behold even as you feel bile churning in your stomach.

And the juxtaposition of Casca’s rape with Guts carving through his own arm to free himself, to try to free her—it threatens to be too much to take.

And we see how the drawings become more vicious here.

The clear lines gone to this heavy scratching, these broken lines like brushstrokes barely containing Guts. We feel the motion both inside and outside him.

The Skull Knight, of all demons, comes and saves Casca and Guts from the slaughter. They escape, but Casca has been driven mad by the trauma. She gives birth to a tiny Eraserhead looking demon. Guts knows he needs to kill the little demon before it can grow to become something powerful and evil, but it escapes and now haunts him, as we saw in the Black Swordsman Arc.

Casca doesn’t remember what’s been done to her or seemingly anything at all, but she fears Guts, and so Guts leaves her behind in the care of a blacksmith and the only other surviving member of the Hawks. The blacksmith gives Guts his enormous sword that we witnessed at the start of all this.

And Guts goes out into the world waging a war against the Godhand.

He cannot save Casca. Does not know how to heal her wounds.

But he still knows how to kill.

And now vengeance drives him and he hopes it will lead to salvation.

all we ask is everything

How much can one person lose?

How much can one person take?

Would it not be easier to give up? To take the deal and give up our pain, our humanity?

When will we escape these shattered bodies?

When will our suffering end?

And the answer Miura gives us at the conclusion of this arc is that it never ends until we die or become a monster.

Open Your Eyes

When people describe Berserk, they understandably settle on the bleak brutality of it. I understand this and agree that it must be done. You cannot tell someone to read this and not prepare them for all the violence, the cruel rapes, the callous depravity.

But I think we do this series a disservice when we leave it there.

Yes, this is bleak and deranged and foul. But all of that is done, I think, in service of hope.

That’s not to say that Guts feels hope, especially at the end of this arc.

But Guts is a Way. He is a Path.

To be human is to suffer.

Yes.

But we may choose to face it bravely, to keep on going anyway, or to shatter and fall apart, to die, to leave suffering and horror behind.

I do not believe that suicide is wrong, nor do I blame those who choose to end their lives.

How could I?

I have spent much of my life wishing for death, seeking it.

But I am not dead.

I live. And I wish I could give you an answer to so much of this, to so much of my life and who I’ve been.

I didn’t survive because of philosophy or theology or some grand understanding of life or because of some grander meaning, some truth or belief.

I survived because of one simple choice that I kept not making.

And so I carried on. Kept walking. Kept holding myself together.

But what gave me the strength to keep on going was all of you. All the people I have known and loved. All those who have loved me.

Friendship. Love. Beauty.

It is so simple. It is so little.

And yet it is everything.

And I do not know how often I’ve encountered a work of art that strikes this potent lesson more powerfully than Berserk.

The depths of tragedy here are astounding and they only work because of all the hope and love we found along the way. Yes, things are bleak and dark and violent, but, somehow, Miura also gives us immeasurable beauty. A staggering gorgeous vision of friendship and love.

Of what it means to hope.

To dream.

To believe in a better world. To believe that we can be healed.

We cannot be saved, no. I do not think that and I think Berserk tells us on nearly every page that there is no salvation. And this, to many, is where the bleakness of Berserk becomes an inescapable monument, I imagine.

We are cursed to be free. Cursed to be human.

But there is great beauty there.

To be human.

To live.

It is, in fact, everything.

And it fills me with tremendous hope. To know that even though we cannot be saved, we can live on. We can carry our pain and our hurts and we can be beautiful, briefly gorgeous.

But seeing Guts leave to fight when Casca needs him most is also enough to cripple me.

For the tragedy continues. And I’ll be back in a few months to write about the Conviction Arc.

the dream is over; it never ends

Wolf.

Howl.

Free books

As always: damn, man.

1) Know that your sons aren't the only ones learning strength and resilience from you. Thank you.

2) As much of a manga expert as I am, I've still not read past the first chapter of Berserk. I think it's because I'm constantly in such a state of fragility that I'm deeply afraid it might shatter me, even if that shattering is only temporary. I think I will read it some day, when I'm feeling stronger. Or perhaps, more likely, when I'm feeling like being shattered will have less dire consequences.

Been meaning to get into this series for ages. Every time I see it in the store, I'm tempted. So your thoughts on it are keeping that small fire alive, haha.

I've been watching Vinland Saga while holding my new daughter at night - ever try that one? It's incredible.