BERSERK: The Conviction Arc (Chapters 95-176)

or, we hoped and we lost and we hoped again

To view this whole essay, you’ll need to click over to the website. It went rather long so it no longer fits in an email.

Catch up:

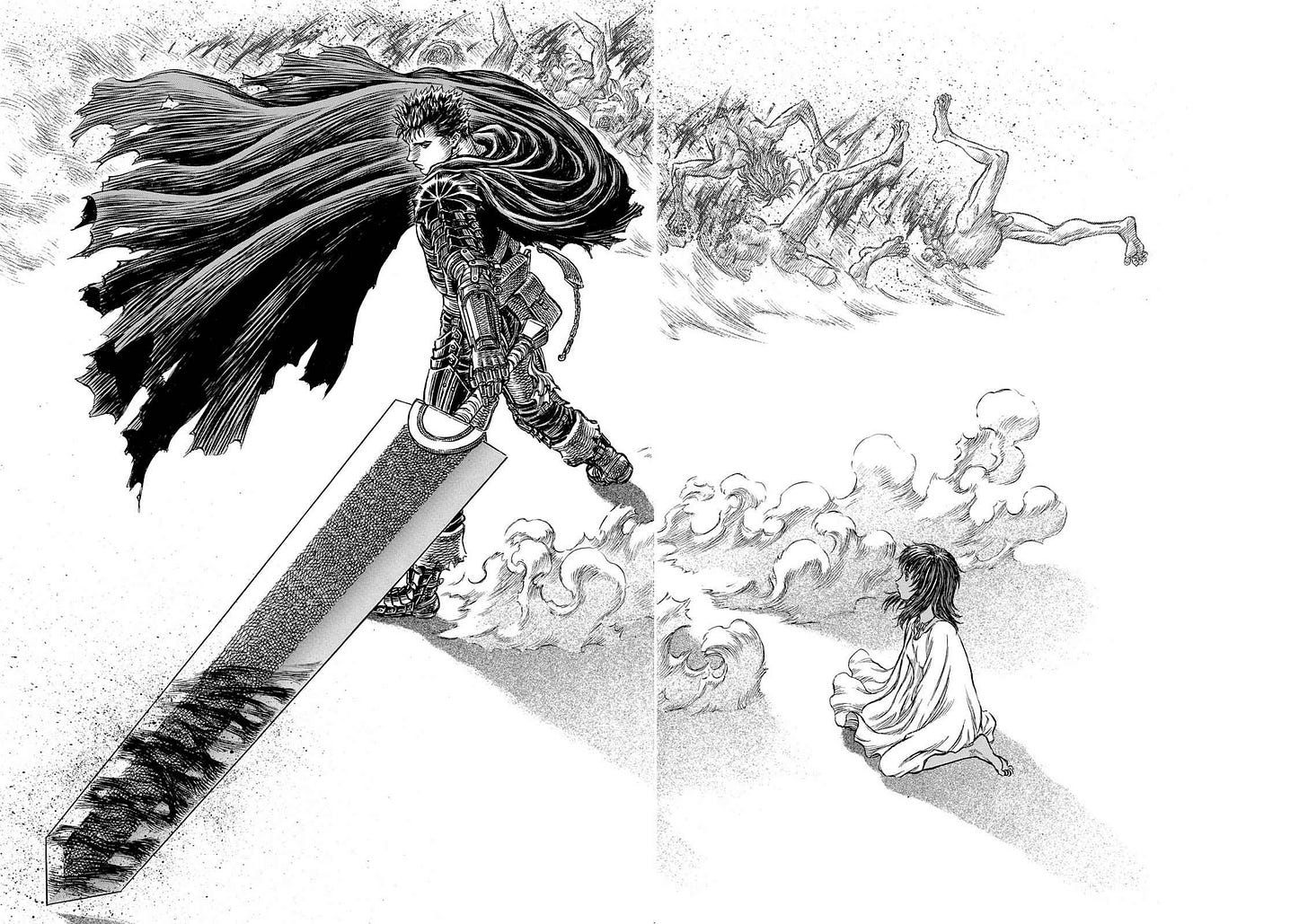

RETVRN OF THE BLACK SWORDSMAN

This brings us back to where we left off in Chapter 8, with Guts wandering the world fighting demons. And we fall back into a looser structure in this Arc as well.

But there’s also a very similar structure in that this arc is essentially given in three parts. Rather than three parts over eight chapters, as in The Black Swordsman Arc, we have three parts spread over eighty chapters.

Enterprising mathematicians in the crowd will be able to calculate how this arc is a blown up reflection of that initial arc.

But I want to consider this overall structure for a moment.

The Black Swordsman Arc kicks off the story and last for eight chapters. We then get a flashback that is twelve times the length of the introduction to this world and story. From there, we return to the present, soaked in violence and fear and tragic loss, and we carry on for eighty more chapters in the present, meaning that we have still spent more time in the past than we have in the present by the time you finish this arc.

Onto the arc itself.

There’s less of the emotional devastation than we just witnessed in favor of some good old fashioned hack and slash action. Some gruesome monsters, some hideous violence, and an interesting development in the nature of Guts’ life.

Hanging over all of this is that we now know Guts. We know what he has done, what he’s been through. The weight of Griffith pressing down on his shoulders, the Casca sized hole in his chest stealing his every breath.

The death of all his friends, who had become a family to him. The loss of all he cared about. The collapse of his whole world.

And a brand carved into his neck. A curse unending, given to him by the man who meant the most to him, who saved him, who gave him a life.

The man who then took his love and raped her before his eyes while he was bound, helpless, by a legion of demons.

And we have the curious naming of this arc: Conviction.

I present to you now, before we amble on forward, that the meaning of this name is significant. The Golden Age is named as it is for seemingly obvious reasons.

It was the best of times. It was the worst of times. But them times was golden all the same.

The Black Swordsman Arc is named in the same manner that a frat might name it’s homecoming weekend something like Blackout 40s or whatever.

And I suppose I’ll play a little game with the meaning of the name of the Conviction Arc, as I see it. You shall read what comes next and I will hope that you guess the reason before I state it at the very end.

such violent children

The opening of this arc presents a strange story of false elves abducting children and turning them into demons. They’re led by Rosine, who was once only a girl, dreaming of an end to pain.

Like so many, this leads her on a path free of pain, of glory, but ultimately of horror as she and the other false elves she creates consume the people of this small village near the Misty Valley.

As a child, she was beaten mercilessly and only found joy out in the wilds, in the forests and streams. The village was a place of violence and privation and fear.

And so we have a Peter Pan twisted death metal black here, where a child forsakes growing up by becoming a monster, Pied Pipering all the children along with her. She is giving them a new life. A beautiful existence with great power where they can live forever without the fear of death, the terror of marauding armies, or the casual brutality of cowardly men broken by war.

Because war is a backdrop here. In the years since the Eclipse, with the fall of the Band of the Hawk, Midland has been drowning in war, as mercenary bands cleave paths back and forth across the land. Worse than that, there’s an invading empire.

Guts and Puck encounter Rosine and her false elves mostly on accident. Guts being who he now is finds only one solution to just about every problem in his life: he swings his big sword.

And though the battle is difficult and hardfought, with Guts once more enduring pain and brutality at the hands of many demons, he defeats Rosine. But only by killing all the false elves, who were once children, who could perhaps have been saved.

Guts deals her a killing blow and she reverts, almost to a child again, and here is where the Holy Iron Chain Knights find Guts and this trail of devastation and destruction. Guts flees and so too does Rosine, though she succumbs to her wounds soon enough.

the seed of disbelief

What are we to make of the Holy See? It’s not accidental that the papacy of our own world is called the Holy See. Much of the iconography and political and theological structure of this sect are marinated in the Roman Catholic Church. They are also quite clearly set up as an antagonist in the same way that the nobility of Midland is presented as an antagonistic force.

This tells us much of Berserk as a story. For who among any of the competing forces has been presented as a force for good? We might say the Band of the Hawk, but only because Guts believes in Griffith. But was Griffith ever a positive influence on the land, on the people?

Charismatic and beautiful and bold and successful, he was, in a way, the promise of war ending. But his plan was to hand that power to the king of Midland until he could establish his own kingdom or take Midland for himself. And while we might want to give Griffith the benefit of the doubt since what he did to Guts and the land came only after a year of torture, but we should remember that even at the height of his power he was not above assassinating children.

We see in Berserk a distrust of all authority. Every power structure is looked at with suspicion and proves itself to be as brittle and nasty as any single individual capable of rape or great acts of violence.

Even our hero, Guts, is rarely heroic in the traditional sense.

Rather, his heroism is Schopenhauerian, Sisyphian, perhaps even Nietzschean, though I’ll have to defer to the philosophy readers when it comes to such things.

And so what in this world is presented in a positive light?

Well, the answer is simple: love.

Friendship.

We can but withstand life. The world is brutal and cold and godless and shrouded in darkness, but we can build a fire together. Your hand in mine and mine in yours. We can form a ring of fire, a brightness, a burning hot to combat the cold, the dark. Our callused hands and feet, our scarred bodies and faces can be turned towards gentleness.

And I’m reminded of another story, another moment drenched in the Catholicism of my youth:

What is more beautiful, my love: love lost or love found?

This doubt overwhelms and undermines me, my love.

To find or to lose? All around me people don’t stop yearning.

Did they lose or did they find? I cannot say.

An orphan has no way of knowing. An orphan lacks a first love. The love for his mama and papa. That’s the source of his awkwardness, his naivete.

“You can touch my legs.”

But I didn’t do it.

There, my love, is love lost. That’s why I’ve never stopped wondering, since that day, where have you been? Where are you now? And you, shining gleam of my misspent youth, did you lose or did you find?

I don’t know.

And I’ll never know.

There are no gods who will save us. No powers to come and protect us.

Only us. You and me. Our tiny hands. Our overbrimmed hearts.

And this is the beauty of Berserk, though you must traipse through blackened fields of shattered bones.

The Holy Iron Chain Knights capture Guts and plan on bringing him in. You see, they’ve been following the path of destruction he’s left. This legendary black swordsman who many in the Holy Iron Chain Knights barely believed existed. At least not as a single man. Another mercenary band, perhaps, ruthless and cruel.

The leader of these knights, Farnese, a noble woman and true believer in the faith, has been tortured by fear nearly her whole life.

Burning heretics forever cast in her eyes give her a sense of power, a marvelous burning in her underbelly, this frothing pleasure in violence, led her to become a blight upon the land, finding and destroying heresy wherever she encounters it.

Her faith in God fills her with righteousness.

But when Guts uses her to escape from the Holy Iron Chain Knights, her whole world is thrown out of order and we spend the rest of her narrative in this arc watching her battle all that she denied with all that she hoped.

Seeing the curse haunting Guts, witnessing the demons and ghosts that he must fight, changes her. For the first time in her life, she sees a limit to God’s light. She believed so strongly in God, in God’s power to crush the evil in the world. She was God’s tool eradicating heretics, snuffing out their power.

She believed so strongly in God that she disbelieved in the demons and monsters we’ve come to know so well over these 150 chapters. Guts’ entire world shaped by monsters, by demons, by men who may as well be demons, and these two perspectives crash into one another, upending Farnese’s worldview.

Farnese’s attendant and bodyguard, Serpico, finds her and Guts and he returns her to the knights, abandoning the capture of Guts.

Here, trying to recover from his many injuries, he’s visited by the demon child once more and sees a vision of Casca burning at the stake.

He rushes home.

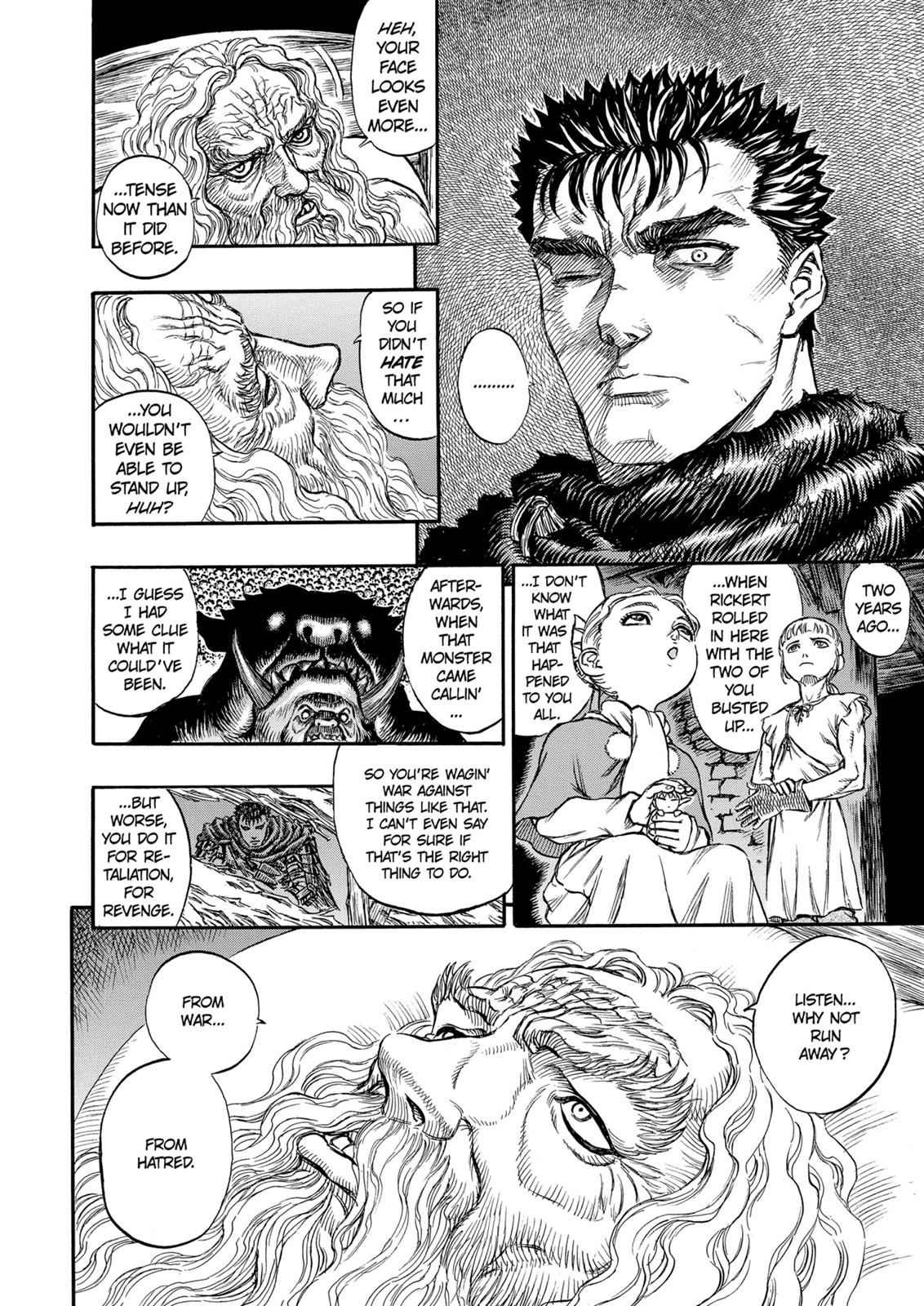

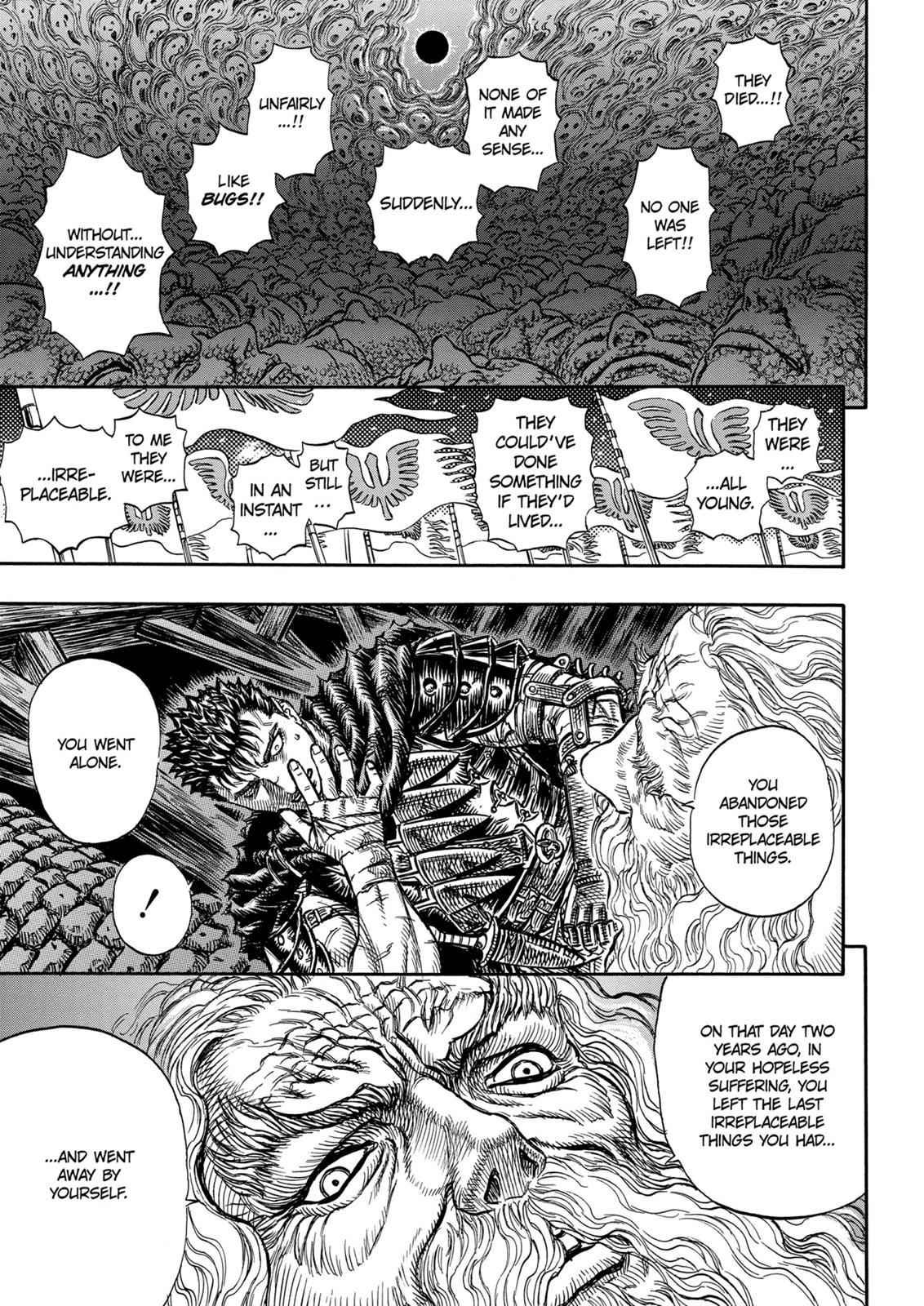

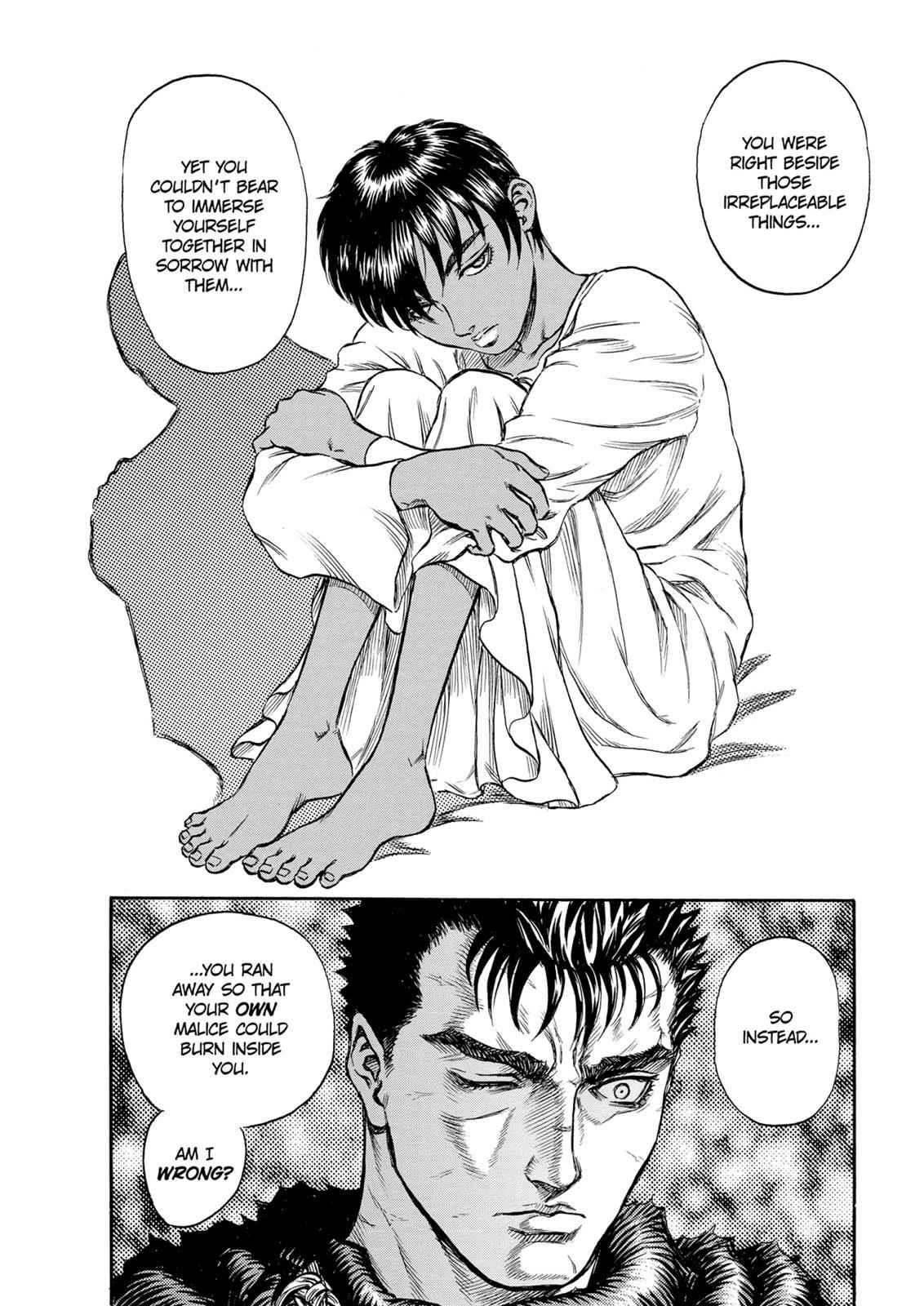

what did you do when we needed you most; or, love asunder; or, I went searching for myself and lost you; or, never let me go, why did you let me go; or—

When I said that there was less emotional devastation in this arc, I did mean it, but I also lied by omission. For though it’s brief, this interlude between hack and slashery is acutely painful.

For Guts discovers that Casca is gone. He has been gone for two years, wandering the land in search of demons and monsters to fight, to gain some sort of vengeance. For this is the kind of man he is.

He does not know how to love. He was only just learning how before everything beautiful and bright was ripped to pieces by legions of demons.

And while I could write 10,000 words on this single moment alone, perhaps it’s best to leave you with Miura’s own words and imagery here.

Run to me.

Come to me, my love.

Do not look away, my love.

Be here with me, my love, always. Always with me. Hold me close. Don’t ever let me go. Don’t you ever fucking let me go, my love.

Guts did the only thing he knew how to do when faced with this ocean of sorrow: he sharpened his blade and went out to kill.

He did it before when he abandoned Griffith.

And damn it. I wish I didn’t, but I see myself here in Guts. And I shouldn’t. No one should. But I know myself. Have been forced to be myself for nearly forty years now. I cannot lie to myself to myself.

I close myself to people. Have done it for my whole life. It may not be a healthy response to sorrow and pain, but it’s the one I’ve continually leaned upon. I wrote about one such experience here.

But like all of you, like all of everyone, I have been hurt. Hurt in love, hurt by love, and sometimes this shattered me. But at times, I learned that the way to not shatter was to build a wall and turn away. And I found a strange capacity to shut myself off from people, even those who once meant the world to me, who were my everything.

I found I could forgive people and get past these hurts and sorrows, but rarely did it ever lead to true healing. For I could not forget. Could not turn my heart back onto them, could not open myself to be hurt that way again.

And so I understand Guts.

Understand why he left Casca behind.

Why he could not look at her. Not because she was raped or anything like that, but because she was the totem of his own failure, the sigil of his own inadequacy, a burning sensation reminding him of how he failed his love, how he could not protect his heart.

But that love never died.

And in a way, the vision of her burning and her disappearance allow a path to healing. For this is something he knows how to do.

If she’s in danger, he will go there and he will kill.

It is the only thing he knows.

In a way, it is all he is.

And that belief, that reflection he sees of himself, terrifies him.

His own failure shrieking back at him from Casca’s face.

The horrors they lived through. The love they shared.

Guts cannot face himself.

He cannot face her.

Cannot live with himself and so he threw his body into an endless war, leaving his heart to wilt and rot. And that heart became mute, unbound by memory, bound in an elf cave to keep the demons at bay.

the herald—hear her singing

The Skull Knight finds Guts once more and warns him that the Falcon is returning to the physical world, through some great terror similar to the Eclipse.

Here we meet the Holy See’s Inquisitor Mozgus who has come to the city of Albion to root out heretics. Farnese, after her failure, has lost command of her knights but she’s at Albion to assist in finding the heretics and killing them.

We find a swirling mass of chaos here and, interestingly, a heretical sex cult flourishing underneath the nose of the Church.

Casca, mute and seemingly helpless, is taken in by the prostitutes of Albion and inadvertently becomes an emblem of purity round which the sex cult goes bananas. This is, of course, the moment when the heretics are found.

Guts is also now here and he’s found a new hanger on—an orphan who, along with Puck, adds a bit of levity and humor to the whole dark affair.

Albion erupts into seven kinds of chaos. Farnese is having a dark night of the soul, doubting everything she’s built her life upon, and Serpico is there to stand beside her, no matter the direction, while Guts cleaves his way through everyone and everything to find and save Casca while prostitutes of Albion try to find a middle path through this chaos while Mozgus believes his connection to God will usher in a new shining day.

But his belief in God has allowed corruption into his heart, into his soul. And while he believes the power surging into him is God’s, it is, instead, the Godhand’s.

And Albion, like so many places Guts comes to, falls under the shadow of these great demons.

Humanity sheds from people and they rage and Mozgus becomes a great demon believing himself to be a magnificent angel and Guts, once more, like always, throws his body in the way and fights.

Clinging to his pain. Clinging to his humanity.

But most importantly, he has found Casca.

And he will protect her.

But does she know him?

And how this breaks him. Yet fight he must. There is no time to break and fall apart.

Albion and the Tower of Conviction at its center swirls with the dead, with demons, of ravaged and deranged souls seeking salvation. And the battle ensues and now Guts, for the first time since the Band of the Hawk, has companions fighting alongside him against great evil.

And Casca is with him.

And the tower falls.

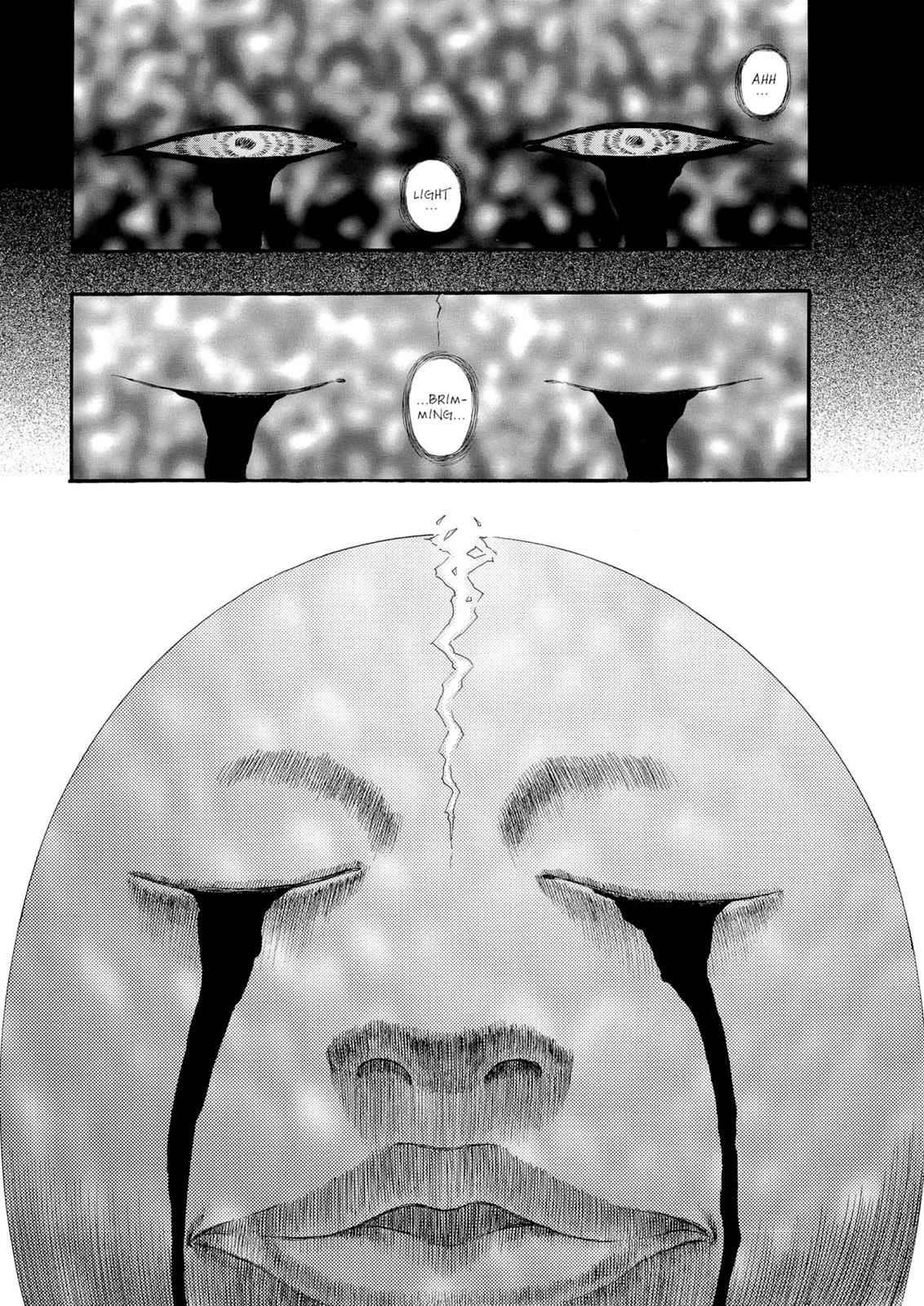

And a light, in the distance.

Griffith returns.

And we close the book on this arc.

a name

And so, dear reader, I must ask what you make of the title: Conviction Arc.

This arc is obsessed with belief, with how we perceive ourselves and others, how we compile the world in our own hearts and heads. And what we find in every case, whether it’s Farnese or Rosine or Mozgus or even Guts, is that they are wrong.

Or, not wrong, but deluded.

Conviction: a firmly held belief.

And what do we believe in more than our own view of the world, of ourselves?

And so I find it fitting that this arc titled for conviction is really about delusion and the lies we believe about ourselves and others. It’s about all that we cannot see or all that we refuse to see.

Only through other people, through a balancing of perspectives, do we begin to see ourselves and the world with any clarity. Which fits the narrative structure here, since it is the arc that most often strays from Guts. We spend time with Farnese but also with characters that seem quite minor. Yet each of these minor characters tell us something important about Guts.

Though, of course, they are not themselves commenting on him. Rather, they are speaking about themselves. But what they see gives us a framework for understanding Guts.

The power to protect someone and the power to be with someone are different.

This sentence may hit like a truck if you’re unprepared.

For true strength comes from caring for others.

This grand epic drenched in black and painted grotesque is really one of love. And this is what continually impresses me, completely shocks me over and over. Because in all the hack and slash, I somehow, once again, forgot what lies at the heart of all this.

All that is beautiful, all that’s worth preserving, is our bounds to one another. Our relationships. Friendships. The love we share and the love shared with us. Kindness given and received.

While Miura got you in the door with sex and violence, we’re nearly 200 chapters into this because of what he delivered alongside that. If all we had was the violence, the demons and the fucking, we would have grown bored by chapter 50.

Instead, we race ever onward to see the path of love, the road to healing, the many storms we must endure to be human, to remain human, to find and give love, to earn and deserve, to share it even when we don’t.

More words that tell us so much given by a character who seems completely unimportant.

This is a narrative trick, mind. To feed us a thesis through the side door. Rather than putting these words in Guts’ or Casca’s mouth, they’re put elsewhere, given to us rather than those who truly need to hear it.

It is a different form of brutality.

But these contrast so completely with what Guts said at the end of the Black Swordsman Arc, where he castigates those for being weak, telling them to kill themselves if they’re not willing to fight the darkness, the evil of this life, this world.

But what strength there is in kindness, in love.

welcome the Falcon

Griffith has returned, not as the demon he became, that we saw, but as a man once more.

And what does this mean for Guts?

For all of them? For all of us?

While I do think this is weaker than The Golden Age, it is also a profound statement. This statement would mean nothing without the horrors of the Golden Age, without the love and heartbreak. And so it must build upon rather than forge its own way, like The Golden Age did.

But what I’m finding is that even a weak stretch of Berserk is better than many other stories at their best. More and more, I understand the devotion this series has, the reputation it basks in.

I’ll see you before the end of the year with the Millennium Falcon Arc, which is the longest arc and the final arc completed by Miura before his death.

Free books: