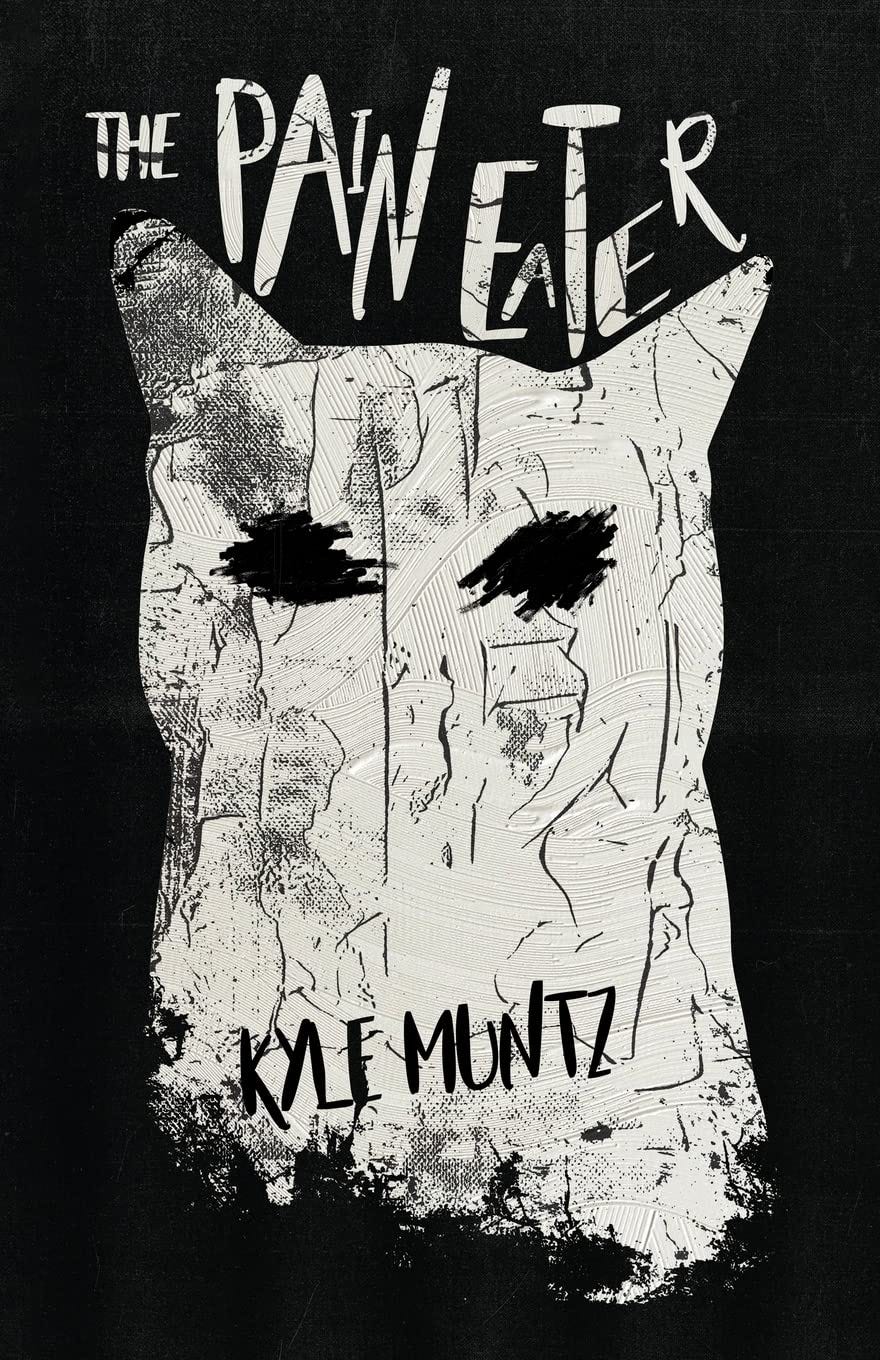

Guest Post by Kyle Muntz. Pre-order his upcoming novel from Clash Books. I read an early draft of this novel and loved it. It’s creepy and funny and sometimes the body horror will make your skin crawl. Follow him on twitter or instagram (especially if you like food).

If you’d like to submit your own writing for a future Guest Post, please see the post here.

Are the people in stories like us, really? Looking over Goodreads reviews, characterization suddenly seems very simple: it’s successful if readers feel they “connect” with the characters, and a failure if they don’t. A surprisingly narrow range of things draw us to these imaginary human beings. Mostly, it seems, readers want to admire characters. Sometimes they’d like to be reminded of themselves. In a Hollywood movie or (especially) an anime series, it’s usually enough if the audience just wants to have sex with them.

For better or worse, I was in my mid-twenties before this began to bother me. Unlike most actual homo sapiens, people in stories effortlessly give up everything to do the right thing. They truly believe in their values and act on them; they have a clarity of purpose, the shining lucidity of a Newtonian comet shooting through moral space. Every few minutes, someone is casually quitting their job to fight for a cause or risking their life to help a stranger—and each time, an invisible hand in the narrative encourages the audience to believe, This person is like you.

This is all fantastic, of course—except, increasingly, I’ve been unable to escape a feeling that not only do characters in stories not remind me of myself, they don’t remind me of anyone. Their vaguely alien psychology haunts me when reading certain novels but especially in film and television, where narratives are regularly built around ritualistic codes of self-sacrifice. Many stories begin with characters being selfish or neglecting some responsibility, but soon enough (often at the least believable moment of the narrative) they’ve left all that behind and fall smoothly into the ranks.

Writers go to extravagant lengths to present their characters as caring more about other people than they do than themselves, especially the protagonist—and most narratives do their best to make it easier. Reality contorts around these uber-people as they find simple solutions to unsolvable problems. Every twist of fate seems determined to teach them (and us) a lesson. All the messy details just fall into place. And in the end, it all leads to that moment when something meaningful is done—not to make money, or to get laid, or look good, but just because it’s the right thing to do.

As a teenager and even a college student, the existence of this kind of hero seemed obvious to me. Somewhere out there, I imagined, were thousands (millions?) of noble humans fighting selflessly for good, not just virtue-signaling to show they’re members of the team. Even insatiable capitalists, fascists, and neo-Nazis identify with the same characters and seem to imagine they’re helping the world. (My gut tells me wall street bankers watch Hollywood films and feel they’re the guy who would never steal the money.) But my suspicion is most real motivations sound bad when they’re spoken out loud, even to ourself; and anyone who pretends otherwise is probably just good at image-control.

Where on planet Earth do we find the pure, noble selflessness that so fills our narratives—a shining goodness untainted by careerism, egotism, or greed? Real people love to help—but especially when others are watching. Behind our piety lurks ominous cultural conditioning built on the fear of shunning or death. We relish in arguing about our beliefs but are notably more hesitant to act on them, especially when there’s no immediate reward. Often, when we do manage to “make the world a better place,” we do it in ways that are inconsistent, hypocritical, or just happen to fit into the exact lifestyle we were living before. We certainly aren’t going to sacrifice our job or reputation. Mostly the best we can do is make an angry post on Twitter.

For thousands of years, narrative has fed a hunger for role models we can admire from outside—people who are stronger than us, more determined, and just happen to fall in line with the dominant values of the current society. Every Marvel movie draws from a tradition of larger-than-life personalities that goes back further than Homer; even what we call “realism” is only a few hundred years old.

But why bother, when real people are just so dumb, boring, and honestly kind of nasty in comparison? A protagonist who shares our actual, day-to-day motivations is discomforting, whether it’s the unbearable compulsions of group normativity, spurts of laziness or annoyance, or just the stubborn desire to prove we’re right. On a day-to-day basis, our most noble impulse is probably to be polite, pay back a debt, or spend a bit more on an “ethical” brand. Yet many of us can identify only with a certain kind of imaginary being: creatures so pure and simple they might as well be aliens. And beneath our admiration lies another level of denial as we attempt to believe that, inside, maybe we’re a bit like them, but they’re also not like us, because they don’t have all the bad stuff.

What is inside the locked box of a human’s skull? “Selfishness” would be the first, most cynical answer, and there’s an emerging brand of modern narrative (HBO’s Game of Thrones is a good example) that reduces characters purely to the desire for power, money, or sex. But actual people aren’t just motivated by greed, and for some reason stories are hesitant to include these other things as well. Writers invent convoluted altruistic motives rather than admitting their characters just want to look good. To belong. To feel good about themselves. To fit in their own skin: like somehow what is inside and outside them matches.

Yet to be alive in 2022, judging from my Twitter feed, is to feel something is off. Every day, we grow a little more annoyed with the wrongness of the world. We want to do something, but we can’t. Everything is just too hard; the odds are stacked against us and always have been. Most of us will never get the respect we feel we deserve. We will never personally vanquish our greatest enemy or punch Nazis in the face. Every day is its own minor defeat; even the small victories hardly satisfy when we know the war is already lost.

But that’s too depressing, isn’t it? And sure, somebody like Karl Ove Knaussgaard writes about the small frustrations and defeats of daily life. But for the most part, it just feels better to imagine everything is simpler. The word “fiction” already implies the opposite of reality, but fantasy is pervasive even in “realistic” stories. Somehow, it’s deeply pleasurable to immerse ourselves in this comforting, streamlined, yet ultimately illusory version of reality, a place where right and wrong mean something, and humans aren’t just petty animals projecting their fantasies onto the small corner of a hollow, cold, yet somehow vaguely malicious universe.

On a more basic level, it’s possible we’re simply hungry to do something. Whether it’s our suffocating daily routine, the corrupt laws of a government we despise, or the unshakable edifice of public opinion—the world itself seems to conspire against us. Half of the time we can’t even yell at that piece of shit at work who we know is causing drama for no reason. We want to fight for our beliefs, but when an opportunity to speak out appears, suddenly saying something seems embarrassing, and wouldn’t it be easier to just post about it on the internet? Even when we do act, often there are unfortunate consequences, and our grand moment leaves us feeling dumb or full of regrets, and maybe we’ve even made things worse.

In fiction, characters know what they want and they make it happen. They encounter obstacles, but their actions have consequences. They affect things. They visibly change a world that (however subtly) revolves around them. They suffer, but even their pain has value. And along the way, they help to propagate a story we all want to believe: that individuals—who aren’t born into billion-dollar fortunes—do indeed have the power to change the world if they just act.

In a workshop, to call a character passive is a damning criticism. The familiar sentence falls like a hammer: “This isn’t right,” they say. “The story just happens to them—they aren’t doing anything.” And the unpleasant feeling is real. By this point, we’re so used to boldness in our narratives that we now take it for granted. We feel scorn for the weak; our cup runneth over with confidence that, in their circumstance, we would do better. Yet, at the same time, witnessing their weakness make us feel powerless, trapped, a way stories should not make us feel, because this feeling is....

Well, it’s like life. And isn’t life just the worst?

Just like in real life, we hunger for our characters to be on the right side. Whether it’s problems in our relationships, a conflict at work, or our battle to change the world, all of us know that—yes—we’re not perfect, but at least our heart is in the right place. When you look closely, aren’t we more good than bad? Probably we haven’t accomplished much today, or last year, or over the last decade or two—but someday we might. And every time we turn on the TV, it’s nice to see characters who reflect everything we would like to be. People who are like us but also kind of better. On occasion they even seem to do our work for us.

But are we, ourselves, likable? I can’t begin to answer a question like that. But whenever I open the black box of another person’s mind—whether it’s a biography or a deep conversation with a person I thought I knew—those familiar elements are always there. A part of me would like to believe they are unlike me: that they’re somehow purer, devoid of the small moments of selfishness, pettiness, and sheer idiocy that define far too much of my experience of this world. But I’ve yet to find much evidence of that.

In the end, of course, life is like a story in another important way: we have to like ourselves as we live it. And most of the time, if we’re lucky, we’re happy with who we are. But when we really look into the deep, black void of ourselves, what do we see? Would you be willing to show everything in there to someone else—and would they like it?

Often I glimpse a different fictional character who may exist only in my mind: a bright, glimmering image of myself as (I wish) I appeared to others. But why does it hurt so much to consider that person might be a lie? Why does the gray, painful light of realization only illuminate things I don’t want to see? Whatever the reason, I know I’m constantly working to forget. And sometimes—for days, even weeks at a time—I succeed.

But the shadow never disappears entirely. Sometimes it’s the looming awareness that even my relatively pleasant life is far from the grandiose adventures I once imagined for myself. Every day I drift, rudderless, towards the cloudy ambiguity of my own future; I encounter more evidence that my life is utterly inconsequential. But worst is a suspicion that, beneath it all, I’m maybe even kind of lame. And that’s the worst part, isn’t it? Like, who cares about a story when you’re not even sure you like the main character?

Then again, when it gets really bad—at least I can go read a novel.

"In the end, of course, life is like a story in another important way: we have to like ourselves as we live it." Going to be chewing on that for a minute.

I preordered the book!