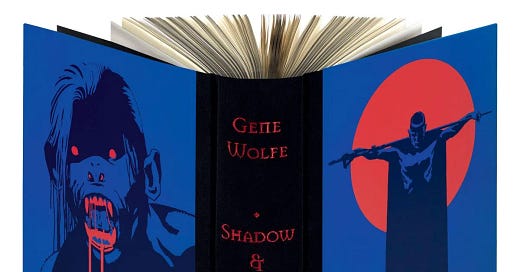

The Shadow of the Torturer: Chapters II & III

Severian & The Autarch's Face

Memory oppresses me.

Me too, Severian.

Me too.

But as I wrote about Chapter I last week, I already pointed you all to the essays in which I discuss memory so we’ll move past this thematic element and how it ties to my own life and instead drizzle on towards what this all means for Severian.

If you would prefer not to receive emails for this slow read, you can adjust your settings by going here: radicaledward.substack.com/account.

There’s much to be learned about the world in these two chapters today. First, Severian explains what the torturer’s guild is and who becomes torturers. We see terms like Corpse Door and optimate and exultant and Witches’ Keep and necropolis and so on and you either nod along, putting all these bits of nomenclature in your back pocket, or you mutter and grumble and flip back and forth in the book looking for a glossary or some kind of indication of what any of this means.

I have bad news for those of you looking for definitive explanations.

But I’ll say this: if a term is unfamiliar and you simple must know because of the way your skull vibrates with the unknowing, pick up a dictionary—maybe one of those fancy ones with etymological information in it—and look up what these words probably mean in modern English.

It’ll set you on the right track.

This second chapter of the novel taking place after the first—because where else would it be?—takes place before the events of chapter one. This is a bit of a callback to Severian telling us in chapter one that he’s beginning his story with a symbol rather than with something else, like the early days of his youth.

But that’s what this chapter is. In the briefest but most evocative ways, we learn who Severian is and how he came to be a torturer.

An orphan. Whose orphan? Who can say? But he implies that sometimes these orphans are the children of exultants or other storied families. Or at least they believe themselves to be. And Severian is no different, taking a coat of arms for himself from an image above a mausoleum door.

Oh, by the way, in case you missed that, these young torturer apprentices make the necropolis their home, spending time in mausoleums and sarcophagi. They each lay claim to their own private mausoleums that they show no one, and in this way take ownership of something in this world of Nessus.

Well, perhaps I should at least say what the necropolis is. If you know any Greek or have just heard words that use necro and polis, you can probably put it together. So necro comes from the Greek word for death/corpse and polis is the suffix that means city. In this way we can construct what this place is.

It’s not simply a graveyard, but one so large that it may as well be a city. Some of the graves are fresher, and these are protected by volunteers patrolling the necropolis while others are ancient. The mausoleum Severian has made into his private space has sarcophagi that have been emptied of their bodies and Severian lies in those cushioned interiors, dreaming of what his life might be. There are a few sarcophagi in his mausoleum that are still intact as well.

Here, he hides the coin from Vodalus.

This chapter still contains the hazy darkness of the first but there’s also something almost Dickensian about it. What we have, here, is the start to a bildungsroman, which is a German way of saying a sort of coming of age story. It’s just that instead of Oliver Twist or Great Expectation’s Pip, we have Severian, the torturer, the eventual thronesitter telling us this tale.

There’s a humor to that and if you can’t see or hear the dark and oppressive comedy in using this technique to tell this story then I suppose we have different sensibilities.

I find that I am often alone in finding certain books funny. For example, Dorothy Dunnett’s King, Heareafter which had me howling, cackling, but which no one else I’ve ever met found funny at all.

I often say the same of Louise Erdrich and Cormac McCarthy, two of the funniest writers of the last fifty years.

But we also see how growing up in such a place gives it a sense of fondness. Perhaps even nostalgia.

The necropolis has never seemed a city of death to me; I know its purple roses (which other people think so hideous) shelter hundreds of small animals and birds. The executions I have seen performed and have performed myself so often are no more than a trade, a butchery of human beings who are for the most part less innocent and less valuable than cattle. When I think of my own death, or of the death of someone who has been kind to me, or even of the death of the sun, the image that comes to my mind is that of the nenuphar, with its glossy, pale leaves and azure flower. Under flower and leaves are black roots as fine and strong as hair, reaching down into the dark waters.

Do you feel that? The loving embrace of childhood, even one mired in death? He has lived so close to death and death has become a part of him, even more than the trade. He sees death as a water lily (that’s what a nenuphar is, though this one is far stranger—something we’ll return to in Chapter IV), and I see it too.

And I see myself in Severian for a moment. A moment that makes me exhale and remember a November afternoon in 2004 when I—

We also learn from Severian that the torturer’s guild is essentially despised by everyone, including the other guilds, but especially by the tenement folk surrounding the Citadel.

The same presentment that told the guards our identity often seemed to inform the residents of the tenements; slops were thrown at us from upper windows occasionally, and an angry mutter followed us. But the fear that engendered this hatred also protected us. No real violence was done to us, and once or twice, when it was known that some tyrannical wildgrave or venal burgess had been delivered to the mercy of the guild, we received shouted suggestions as to his disposal—most of them obscene and many impossible.

Previously, we also learned that women were once torturers but have not been allowed into the guild for centuries because of the innate cruelty of women.

I bring this up for two reasons, and we’ll attack them in order.

First, Severian is aggrandizing the guild. It takes a certain type of person to be a torturer. You see, people not of the guild are much crueler to criminals and nonconformers. The implication is that the torturers are fair.

Never does Severian, here, question the existence of the guild. It has always been here and though it’s diminished in size and prominence it remains part of the Citadel.

Second, we get the first glimpse of Severian’s attitude towards women. Some people say that this simply mirrors Wolfe’s view of women and maybe that’s true but I find it the least interesting thing to discuss here so we’ll narrow our focus just to Severian.

Severian, by his own admission, lives only with boys and men. The masters of the guild and journeyman, too, live and interact only with men, for the most part. And this has been true for centuries, which engenders a certain culture of the guild.

Why must there be no women?

Well, perhaps it’s because they’re too cruel to do the job.

This gives the guildmembers a sense of moral clarity, a belief in their own righteousness. Their circumstances guide their perspective of the world, one could say. And Severian came up through the guild and so it’s unsurprising that he holds these childhood ideals and beliefs even many years later, while he narrates his life.

And remember, he is telling this story to an audience.

The chapter ends with Severian swimming in the Gyoll river and nearly drowning. Or, he does drown, but he’s revived. While under, he sees his dead Master Malrubius but he also sees the enormous face of a woman.

Something godlike and immense.

Darkness closed over me, but out of the darkness came the face of a woman, as immense as the green face of the moon. It was not she who wept—I could hear the sobs still, and this face was untroubled, and indeed filled with that kind of beauty that hardly admits of expression.Her hands reached toward me, and I at once became a fledgling I had taken from its nest the year before in the hope of taming it to perch on my finger, for her hands were each as long as the coffins in which I somttimes rested in my secret mausoleum. They grasped me, pulled me up, then flung me down, away from her face and from the sound of sobbing, down into the blackness until at last I struck what I took to be the bottom mud and burst through it into a world of light rimmed with black.

Severian is saved and he assumes his friends saved him and he doesn’t even understand when the people of the tenements who have come to care for him, to bring him food and blankets, tell him that he shot right out of the water.

One of them asks him if he saw a woman while he was below and his friend, not understanding, says that there are no women in the guild.

This curious moment that Severian chooses not to linger on or explain or clarify has him seemingly saved from death by a goddess that may be known to the tenements denizens by the river.

But they are so separate, the people and the apprentices, that they cannot quite understand one another, even as they’re bound together by this almost—tragedy.

For the people, despite their disgust with the guild and its apprentices, trat with Severian like any boy who nearly died.

An entire novel could exist right here, at the river. But instead we’re already past it.

What happens next in Severian’s life is what happens in chapter one. So chapter three picks up after.

This curious construction is why I wanted to take these first three chapters slowly.

It’s worth asking why Severian and, by extension, Wolfe, decided to tell the story this way.

I don’t have an answer. I simply don’t know. But it is worth thinking about.

Next we get much more about the Citadel itself and the daily happenings of the torturer’s guild. Across both chapters, you read words like bulkhead and port and when you consider that there’s a massive cistern that people can swim in, you begin to, possibly, form a picture in your head of what the citadel and accompanying towers might be.

Why would you describe a tower as having a bulkhead?

When you consider some of the other breadcrumbs tossed our way, like that there are sometimes visitors from the stars, you may form a picture of towers as spaceships.

Or maybe not!

But maybe you should.

One important thing revealed about the working of the guild is that one of the most important rules is to not listen to the things people say under torture.

How strange! You may assume that the whole reason for the torture is to learn something, for these people to admit something, but, alas, that doesn’t seem to be the case.

So what is their purpose?

“When a client speaks, Severian, you hear nothing. Nothing whatsoever. Think of mice, whose squeaking conveys no meaning to men.”

Consider the euphemism of client and their separation from men.

We’re learning the inner workings of the guild and how one rises up from apprentice, eventually, to become a master just in time to discover that the Autarch’s army has won some battle and so many new people are headed towards the Matachin Tower to be tortured.

We also learn that Severian is about to be the oldest apprentice, since his friends are graduating to become journeymen of the guild.

But, here, in this third chapter, we begint o narrow focus on the tower and Severian’s life.

So consider these three chapters.

One: We are given a dramatic scene that sets Severian on his journey where he eventually backs into his throne.

Two: Severian explains the conditions and circumstances of his childhood while also describing the shape of Nessus and the Citadel, the seat of the autarch. The fact that Severian is explaining this is important for two reasons: the first is that he’s explaining a city to people of this world who would not be familiar with this place, and the second is that he is explaining to us, the audience outside of this world, the one holding the book in our hands, what this place is. Further, he’s showing us that he was saved as a child by a goddess just in time to save Vodalus.

Three: The inner workings of the Matachin Tower and the torturer’s guild, which will soon be full of clients from a war in the north.

And that, as they say, is that for now.

Curious to hear what people think about these chapters and if any questions came up.

Next week, we’re doing Chapters IV and V where we’ll discuss how a word used by Severian does not necessarily correlate to the word as we understand it.

Glossolalia - A Le Guinian fantasy novel about an anarchic community dealing with a disaster

Sing, Behemoth, Sing - Deadwood meets Neon Genesis Evangelion

Howl - Vampire Hunter D meets The Book of the New Sun in this lofi cyberpunk/solarpunk monster hunting adventure

Colony Collapse - Star Trek meets Firefly in the opening episode of this space opera

The Blood Dancers - The standalone sequel to Colony Collapse.

Iron Wolf - Sequel to Howl.

Sleeping Giants - Standalone sequel to Colony Collapse and The Blood Dancers

Broken Katana - Sequel to Iron Wolf.

Libertatia; or, The Onion King - Standalone sequel to Colony Collapse, The Blood Dancers, and Sleeping Giants

Noir: A Love Story - An oral history of a doomed romance.