fluttering scraps of night

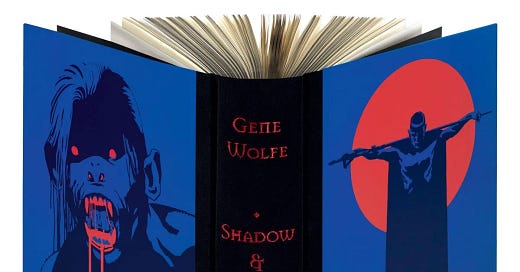

I love this phrase. I love it so much that I’m going to tell you right now that you should read everything Gene Wolfe has ever written. I haven’t even done this, but, even though I’ve read this twice before, this phrase hit me like a thunderclap.

Fluttering scraps of night.

This is in reference to these enormous batlike creatures stalking Jonas and Severian. He describes them as true black, fuligin, like his own cloak. They hunt warmth rather than blood, though blood they’ll take for the heat of it. These are strange, unearthly monsters drenched in the surrealism of the Dying Earth genre, where magic and science have corrupted one another, mixing like some terrible concoction to enliven a blasted dead world with horrible nightmares.

And what a nightmare!

When Severian kills one, it’s like slicing through air.

So easy to kill, yet these things will just as easily kill you. Their near nothingness makes the more frightening rather than less.

But he describes them in this phrase of beauty:

fluttering scraps of night

I want to live in those four words, in those six syllables.

Do you hear it?

Can you hear it?

Can you hear beauty when you read it on the page or do you sit there deaf to the printed ink? Because I hear it echoing in my head.

Fluttering scraps of night!

Haunting and beautiful, terrible and wondrous. This dying earth. This far future nightmare of calamity and awe.

Anyway.

Yet some part of her is with me still; at times I who remember am not Severian but Thecla, as though my mind were a picture framed behind glass, and Thecla stands before that glass and is reflected in it. Too, ever since that night, when I think of her without thinking also of a particular time and place, the Thecla who rises in my imagination stands before a mirror in a shimmering gown of frost-white that scarcely covers her breasts but falls in ever changing cascades below her waist. I see her poised for a moment there; both hands reach up to touch our face.

There’s a strange kind of romanticism here with Severian. Though he is a brute who uses people, who kills them, who thinks of women in a very narrow way, even he is capable of great love.

And these glimpses of what love is to him are fascinating. For, in a sense, what makes him love Thecla is the reflection of self.

Thecla remains ever with him.

Is that not how love always is? Those we love, and especially those we’ve loved and lost, knit themselves to the fiber of our souls. Here, we literalize the metaphor however. Thecla is truly part of Severian now and always. He remembers her life as if it was his own because of the perfection of his memory. And in this way, she is him and he is her, for who are we but our memories. What makes us who we are but the knowledge and reflection of who we’ve been?

Curiously, this turns his own relationship with Thecla into a hall of mirrors. He sees her in his memory and she sees him in hers and forever these reflect one another, distorting the image of the other, but in this distortion, in the chasms between perception, a new truth is found.

And this has made Severian the man he is.

And I fixate on all this because I think it’s important. It may be one of the most important experiences of Severian’s life. It gives greater understanding of why so much of the previous novel was spent ruminating on Thecla. She was his first adolescent love, yes, but those memories are twinned inside him. For he has her always within him.

Beyond that, perhaps the most interesting aspects are that Severian goes on performing his executions for no real reason but to allay suspicion. Which makes sense, given the morality of Severian and this world. For he sees nothing moral or immoral about killing his clients because he is only a tool of state. His role in life is that of executioner—what more could we expect?

Then there’s the fact that Jonas apparently pretends to eat often.

Who is he?

What is he?

Why does he need so little nourishment to survive?

And then the final piece of this: Severian took the task Vodalus gave him but has no intention of completing it. Why? He doesn’t say. Only that he will not do it.

How curious.

How strange.

He pledges himself body and soul to Vodalus and his cause, but the very first time he’s given a task to prove his loyalty, he instantly accepts and then decides not to do it.

I think, really, this is what makes Severian feel so alive, strange as that may sound. He says yes so often, regardless of what he wants. But then he also has no problem in simply breaking an oath or refusing to follow through on what was asked of him.

And so we must ask: what kind of man is Severian?

Or, perhaps of more interest is the possible conclusion that Severian went to the House Absolute with every intention of fulfilling Vodalus’ command but failed, and so in his retelling, he explains that he never planned on doing what was asked.

Who can know?

But I find it a very interesting thing for him to admit so readily.