I grew so accustomed to the sound of the icy water that had you asked me I should have said I walked in silence; but it was not so, and when, most suddenly, the constricted tunnel opened into a large chamber equally dark, I knew it at once from the change in the music of the stream.

Let’s spend a moment on this sentence.

Many writers and teachers of writing will tell you to aim for simplicity. There’s a general idea that shorter, clearer sentences are preferable to readers. I don’t know why anyone would believe this since it’s so obviously not true, but it’s a powerful enough concept that it lives and breathes, feeding on our assumptions of what other people must be like. In part, this is a self serving comparison. We like the complex but those nasty little fools crave simplicity. Such a dirty word when we think it like that.

This sentence winds and stretches to about fifty words and there’s actually not much punctuation, considering how much there could be in a sentence like this, full of dependent clauses and prepositional phrases and even tense shifts.

So consider why.

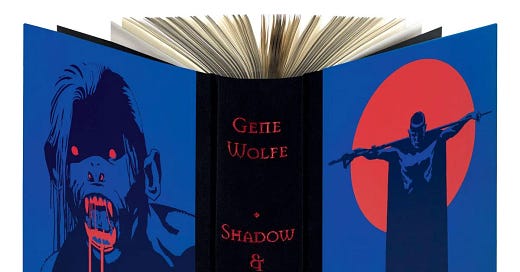

We haven’t spoken of the style of Wolfe’s sentences. I’ve avoided, in general, bogging us down with this kind of careful line reading, but indulge me for a moment.

If you like this sort of thing, I’ve done it once before when writing about Cormac McCarthy.

I grew so accustomed to the sound of the icy water that had you asked me I should have said I walked in silence

Do you hear it as well? Do you hear when noise becomes silence?

I mean, perhaps you don’t even realize it. If you’re alive reading this right now, you live in the loudest era of human history. If you live in a city, you may not be aware of the baseline decibels, the cacophony of civilization surrounding you, containing you. I think this is why noise cancelling headphones take us by surprise when first we put them on.

We’ve rarely ever even heard silence before.

But along with this striking yet familiar sensation, we come to a strange construction: that had you asked me I should have said.

Why did he structure the sentence this way?

There were simpler, clearer ways to do it. But he chose this one. This winding, twisting way to say, “The constant noise became silence to me.” Perhaps it was to use grammar to put us there in the tunnel with Severian. To have us feel the winding, twisting blindness of that space where he searched for Thecla.

but it was not so, and when, most suddenly, the constructed tunnel opened into a large chamber equally dark, I knew it at once from the change in the music of the stream.

Writers and teachers of writing tell you to avoid adverbs but look at how this how sentence hinges on that suddenly.

Again, Wolfe is demonstrating Severian’s experience grammatically.

It’s a wild experience when you slow down to consider it. And perhaps, now that I’ve called attention to it, you’ll notice it everywhere. Not only in this book, but beyond.

That’s the hope, anyway. That a lesson learned in one place falls into your lap elsewhere as well.

Because in this moment, we feel this experience with Severian. For we have all felt the change when we enter a place of differing scale and scope. If, like Wolfe, you’ve ever been into grand churches and cathedrals, you have tasted the cold air within those ancient stone walls despite the summer heat just outside. You’ve heard civilization quiet within and your echoing feet fill space.

We read with our eyes and our visual cortex takes up a huge chunk of our neural anatomy and so we grow accustomed to considering the world only through sight. But here Wolfe is using many sensations. Hearing most of all, but I also feel the change of the space on my skin. I can taste the claustrophobia falling away by the changes in the air on my tongue.

I draw attention to the prose here and now because I could excerpt just about any sentence from this chapter to demonstrate the mastery here. This chapter is, as the kids say, a flex. And what then happens here?

Well, we get a bit of a chaotic setpiece wherein Severian is fighting a horde of apelike men or manlike apes. So in this darkness full of poetry and powerful prose, we get a fight scene!

But rather than Severian winning through might and guile, he succeeds, once more, through chance. By clinging to the Claw of the Conciliator, the manapes halt their assault and seem to revere him. Or at least the light he has brought to their world.

And remember: he came here to save Thecla.

But it was calling out her name that alerted the manapes to his presence and nearly led to his death. Even still, Severian only believes he’s gone the wrong way and Thecla lies somewhere waiting for him.

And perhaps the way I’ve structured these last two chapter discussions has given a bit of the game away, in a certain sense. For perhaps, upon reading this, you believed Thecla was waiting for him, that the ruse was successful, that she escaped the Matachin Tower and certain death.

If she had, do we really think she would be so in love with her jailor, her friendly torturer, that she would seek him out once more?

It’s one thing for Severian, young and reckless and dumb as any young man, to believe that the girl of his dream awaits him after skirting death. But do you believe?

And if not Thecla, who would have drawn Severian out to this place?