There are beings—and artifacts—against which we batter our intelligence raw, and in the end make peace with reality only by saying, “It was an apparition, a thing of beauty and horror.”

Somewhere among the swirling worlds I am so soon to explore, there lives a race like and yet unlike the human. They are no taller than we. Their bodies are like ours save that they are perfect, and that the standard to which they adhere is wholly alien to us. Like us they have eyes, a nose, a mouth; but they use these features (which are, as I have said, perfect) to express emotions we have never felt, so that for us to see their faces is to look upon some ancient and terrible alphabet of feeling, at once supremely important and utterly unintelligible.

Such a race exists yet I did not encounter it there at the edge of the gardens of the House Absolute. What I had seen moving among the trees, and what I now—until I at last saw it clearly—flung myself toward, was rather the giant image of such a being kindled to life. Its flesh was of white stone, and its eyes had the smoothly rounded blindness (like sections cut from eggshells) we see in our own statues. It moved slowly, like on drugged or sleeping, yet not unsteadily. It seemed sightless, yet it gave the impression of awareness, however slow.

I have just paused to reread what I have written of it, and I see that I have failed utterly to convey the essence of the thing.

Who would write this way?

Well, Gene Wolfe would.

We’ll circle back to the opening of this chapter but first we’ll run though what happens. Severian and Jonas discover they have already been on the grounds of the House Absolute, so their attempts to sneak in or infiltrate failed long before they were even aware. More than that, they are captured and bound.

In the distance, they see Jolenta—the object of Jonas’ desire—and Dorcas—the objects of Severian’s—along with the good Dr Talos and Baldanders. This strange reunion happening again so long after the gates of Nessus, after the last performance.

And one may wonder about coincidence, of synchronicity, of the echoes of lives as we pass by. The love we have off in the distance and the way it overwhelms us here, bound and captured.

It’s a simple chapter and basically amounts to telling us how we get into the House Absolute, but we also touch on Father Inire’s gardens, which Thecla remembers so fondly, so powerfully.

But let us return to the opening of the chapter.

Severian writes evocatively for three paragraphs and then tells us that he has failed to express an image properly.

How very strange!

But also how grand. How large this makes these statues. Evocative and grand as he describes them, this pales in comparison. His best attempt falls flat, an utter failure. And then he tries again, but he does it through comparison, through metaphor, through appeals to emotion, to terror.

What humanity could make statues so wondrous, so beyond description, beyond comprehension?

These are the grounds of the Autarch, overseen by Father Inire, who we have heard much about and in contradictory ways.

We also discover that Severian, the autarch, is traveling through the stars, encountering creatures of perfection. Are these aliens or human relatives so long divorced from the humanity of earth that they have become alien? They seem even beyond Exultants, those giant beautiful humans like Thecla and Vodalus. And so this also means that Severian is writing this account after he left Urth.

Will he return?

Where does he go?

And why does he tell us this, why does he tell this story at all?

Whose memories does he conjure?

What is perfection to Severian? Is it like his memory? Is it like Dorcas or Agia or Thecla?

What is perfection to this man of the far distant future?

But I want, most, to live in that opening sentence.

There are beings—and artifacts—against which we batter our intelligence raw, and in the end make peace with reality only by saying, “It was an apparition, a thing of beauty and horror.”

Again, there’s the horror. Beauty and horror.

Perfection and terror. A beauty that overwhelms, that overpowers, that threatens to destroy us.

And though we are but people of this 21st century, have we, too, not encountered sights and sounds that we might describe in the same way? Some of them formed from the natural world but some made from the hands of mortal men and women.

Have you read Virginia Woolf’s The Waves? Have you gazed upon a Caravaggio? Have you heard Beethoven Moonlight Sonata or Henryk Gorecki’s 3rd or Arvo Part’s Spiegel im Spiegel?

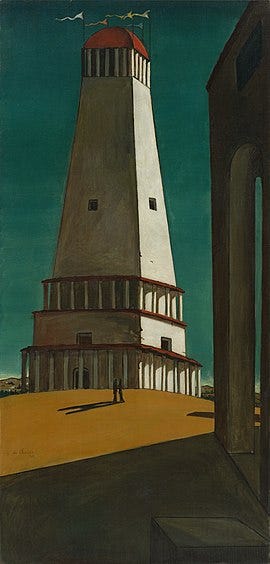

I cannot, in words, describe what de Chirico’s Nostalgia of the Infinite means to me or why I cannot look away, why the scale makes my heart flutter when I stare upon those two lonely figures, their shadows melding, reaching long.

I have drowned in music, in visions, in sensations driven by art, by the aps, by the Cliffs of Maher, by the coast of Howth, by temples so deeply embedded in mountains and forests that you could search for them for days and remain lost, of a shrine on a mountaintop in Japan where the kitsune reign and I became lost, swallowed by cicada songs.

My intellect battered raw, indeed, absolutely, permanently.

And perhaps this is, too, the draw of Wolfe. His unimaginable, indescribable vision of a future so far in the future that it feels, hauntingly, of the distant past. And we come, soon, so a kaleidoscopic vision that absolutely melted my brain, the words bleeding through and right off me when first I encountered it.

And I could say the same of much of the Book of the New Sun.

The New Sun.

Those three words.

Even just the two: New Sun.

What a wonder. What an ecstatic vision.

If you’re with me still, and I hope you are—hope you tell all your friends about this strange, gorgeous, confounding book—then I hope you understand what Wolfe means by that first sentence.

For you are in such a place.

You hold in your hands such an artifact.

A beauty.

A horror.

A mindmelting, life altering artifact.