The Classics are an Escape

or, the timetravelers are wrong about art and life; or, don't blame it on ringo

People fetishize the Classics in a very specifically interesting way. Usually, these people who see Charles Dickens or James Joyce or Fyodor Dostoevsky as the best humanity has had to offer are the same types who will feel embarrassed for you when you bring up JRR Tolkien. They’ll especially view his belief that escapism is good as incomparably naïve and, well, embarrassing. Embarrassing for him for having said it. Embarrassing for you for having repeated it. And, lastly, of course, embarrassing for them for having had to witness you repeating it.

I get it. Elves are lame or maybe racist, depending on who you ask. Books with dragons on the cover are for children (never mind that the soul is healed by being like children). Escapism, in short, is something for the deluded masses, but not the subject of Serious Thinkers. Art should not be an escape. The role of the artist is to not look away. Art is Serious Business for Serious People who think seriously serious thoughts about Serious Ass Shit. Dostoevsky and Dickens and Joyce bring us to the depths of the human heart and reveal what we all wish to bury. They delve into the soul of creation itself and plumb her depths to bring us back impossible glory and beauty. They bring us ART!

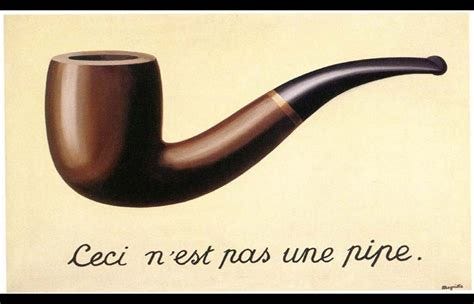

But the Classics, for people of the 21st Century, are escapism.

I once knew a woman who refused to read books written after 1900. She didn’t put it this way, but it seems clear that she thought culture had deteriorated since then and that all writers since then had been dilettantes at best and degenerates at worst. She may have been right, but it’s still a tremendously odd way to approach art and life. In her actual wording, she said that she only read books that have stood the test of time. The time, at this point, in the late 2000s, seemed to be at least a century. Which, yeah, sure, why not. There are probably dumber ways to assess what books are worth your time, but it’s been stuck in my head for over a decade. How a woman born in the late 1980s or early 1990s denied the value of anything written during her lifetime.

I’ve known — and probably you have too — many people who see the 1960s and 1970s as the true and only Golden Age of music of any genre. I remember doing mushrooms in a big empty house in St Paul with a girl who insisted we only listen to Pink Floyd. Which, yeah, I mean, why not. Pink Floyd was good and is good and drug culture — especially of the hallucinogenic variety — is so tied up with psychedelia from 1967–1975 that it made sense to wear tie-dye and dance in the rain while David Gilmour breathed the air in my lungs, while his guitar gently wept round me, while Roger Waters’ bass kept my heart beating in time, while I ran like a rabbit trying to forget the sun on familiar streets made new.

What I mean to say is that drugs are cool and fun, especially when listening to music written by people having fun on drugs. Escapism made viscerally real.

I’ve known people — many people — who, like me, were born in the last half of the 80s or first half of the 90s who believe that the Beatles are the greatest band ever. Which, yeah, I mean, absolutely, sure, go nuts. They turned silence and nights into melodies. What was unutterable, they sang. They made the stand-still world whirl. But it doesn’t stop there for so many of them. They insist, in fact, that most music — especially popmusic — is astronomically worse than what the Beatles were doing. And, yeah, maybe that’s true. Maybe The Beatles and other bands of that era were the plateau of music, and all else has been a precipitous slide to whatever genre of music self-proclaimed audiophiles currently believe is tainting the ears and hearts of young girls (because, let’s be honest, experts always hate whatever young girls like, whether it be Britney Spears or Hip Hop or Reggaetón or Justin Beiber or K-Pop or…The Beatles in 1963), who are too dumb and naïve to possibly appreciate proper music, too starstruck and horny to appreciate anything but the heartthrob behind the microphone or the hypersexual young woman tainting the purity right out of them.

I love movies. In a different life of writing, I described movies as my whole life. I love the glories of the Silent Era, the Hitchcock years of beneficial shocks, the auteur years, and even the big budget nonsense years that are competing (failingly) with the comfortable era of streaming. I love movies of all eras, but ever since I was a child, I’ve been told that certain eras of movies are superior and will always be superior. The easiest rubric to determine if something is worth your time, according to the cineaste, is first to check to see if the director died decades ago. If yes, well, you may be on the right track! Which, I mean, yeah, sure, I get it. I love all the famous names of cinema’s past as much as the next person. Many of my favorite directors are dudes who died before I was born. Some of them even lived and died in Europe or East Asia, like a real Artist of the World.

But I think what I find most interesting about this mindset is how ubiquitous it is in such a specific type of person. In fact, I’m the right type of person to have these views. I’m obsessed with art, obsessive with the greats. I used to watch a movie or two every day. I still read a few books every week (honestly can’t remember the last time I went a week without reading a book). I can quote Virginia Woolf or Akira Kurosawa or Lou Reed from memory. I’m the kind of obnoxious person who can talk for minutes straight without taking a breath about how Arthur Rimbaud invented the 20th Century.

If you’re still with me, can we be honest? If you caught every allusion hidden in plain view in the first thousand words of this essay, can we just admit it?

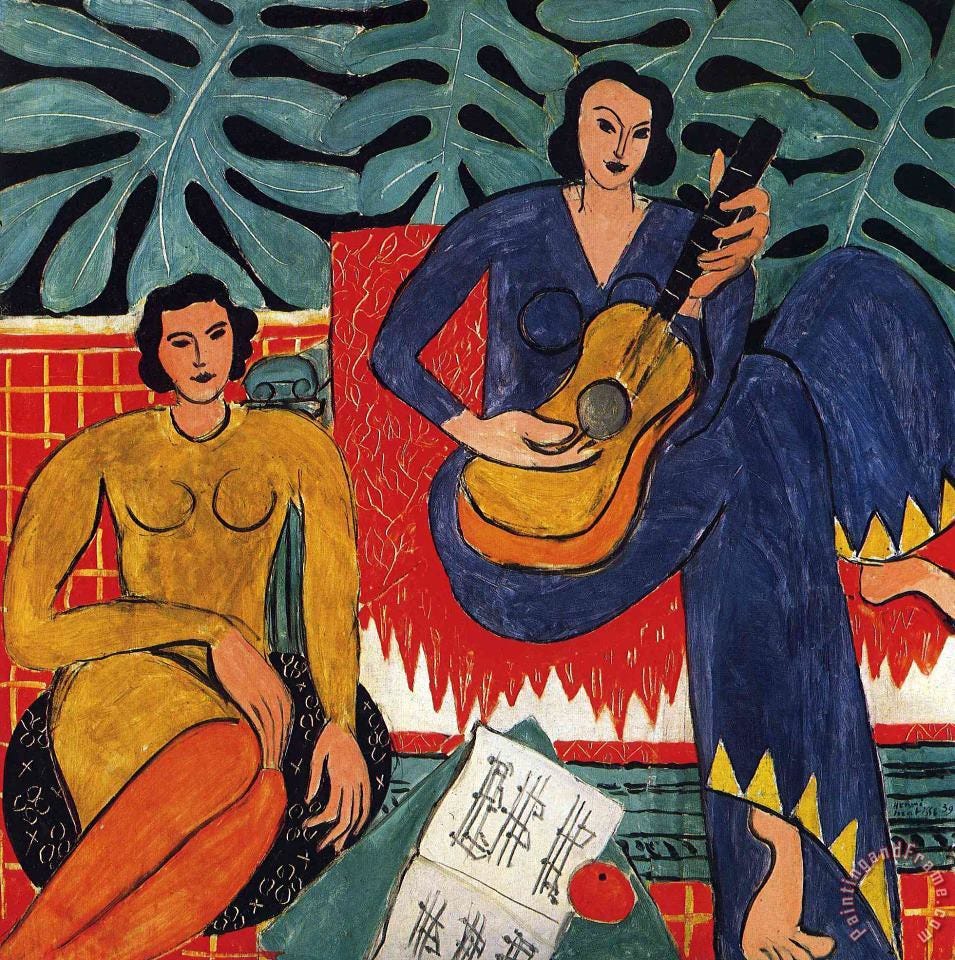

The reason we buried our heads in art is because we were lonely kids trying to escape our lonely lives surrounded by people who we believed could never understand us. We felt so intensely the delights of shutting oneself up in a little world of one’s own, with pictures and music and everything beautiful. Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County and Kurosawa’s Japan were no different to the fifteen-year-old me that obsessed over them than Middle Earth or Asimov’s Galactic Empire. And the older I get, the truer that seems.

When I was fifteen, my favorite bands were Brand New and Taking Back Sunday. I loved Led Zeppelin and The Beatles and Pink Floyd and Joanie Mitchell because however vast the darkness, they supplied light, but none of them spoke to me the same way Fall of Troy’s frenetic metal or The Blood Brothers’ hideous car wreck of love spoke to me. The way Jesse Lacey and Johnny Whitney felt like my own thoughts shouted through another’s mouth.

I remember, even then, thinking that people obsessed with the musical era their parents grew up with were displacing themselves in time. Somehow ignoring the War on Terror, the collapsing American Empire that would result in almost everyone I knew getting buried in debt only to be dumped into an economy that would collapse twice by the time we were 30. Constantly reaching back to the 1960s and 1970s, another period of political and social upheaval defined by a seemingly endless preoccupation with war and civil liberties, felt somehow like a lie. Like a way to make sense of the present, not by engaging with it, but by engaging with a time period, with a social movement, that had a shape and structure, a comprehensible narrative resulting in our parents having careers and buying homes and starting families, assuming our lives would look like theirs. Which, again, yeah, I get it, why not.

I know the appeal of feeling that someone who died a long time ago was writing just for you. I felt it so acutely when reading Dostoevsky for the first time that it nearly killed me. The way his words haunted me, the way Raskolnikov’s tortured thoughts echoed in my stupid skull. But Dostoevsky wasn’t writing for me. Neither was Bob Dylan or Stanley Kubrick or any other artist who meant the world to me when I was young enough to break my own heart over beauty I found unattainable.

They weren’t writing for me because I wasn’t even alive then.

And even when we look back on Dickens and Austen or de Balzac, who vividly recreated their own realities, we see that the appeal was the escapism, the invitation into another world. Take Jane Austen. The world she described was reality to such a vanishingly small subset of English people living at such a weirdly specific time (the Georgian Regency) that never really reemerged in English culture. Most readers of Jane Austen at the time may have been landed gentry or petty aristocrats, but most English definitely were not. Charles Dickens created London for the world, just as de Balzac invented Paris for the world. Many readers of Dickens, however, never saw London. Many of them never even saw England! The same is true of de Balzac’s Paris. I could go on about the stylistic ticks and necessities of the era and why present day middle schoolers find them so needlessly wordy (maybe an essay for another time!), but the point remains the same whether you’re reading them now, in 2021, or in 1850: they were building a world as meticulously as Tolkien built Middle Earth specifically because most readers would never visit the world they described, even though they actually could get on a boat, take a train, and walk down the streets described in Oliver Twist or Le Pere Goriot.

When we use the Classics to measure our lives, we’re unbinding ourselves from time and removing ourselves from the present. Whether that’s good or bad really doesn’t matter. The point is that when you give yourselves to Jimi Hendrix or Ledbelly, you are escaping into a world that was remote even to the people alive at that time. It certainly feels universal, because all good Art is an open invitation rather than a note passed between scholars in gated communities. But that universality comes out of the specific realities and conditions of the time and culture that they were created. You may still connect to them, might connect with them more than art produced during your life, but the same is true for the goth kids playing D&D that you sneered at in high school.

Art is an escape. Even brutally realistic art is an escape. Even when it’s a mirror of society, it’s more like a funhouse mirror with legible, albeit complicated, morality. The artist opens themselves, inviting you into a way of seeing the world that may feel foreign or familiar, tantalizingly addictive or repulsively abrasive, and that invitation is for you to step out of your own life, your own world and culture and perspective. To engage in any art, you need to first escape yourself, enter another.

But, like any journey, we bring the experiences back with us, to our real life. What you learn from Frodo at Bag-End may make you a better friend. Mrs Dalloway’s dinner party may make you a more empathetic lover. George Harrison’s Sitar may be the reason you decided to study religion or become a vegan.

No escape is permanent. Life is bringing the lessons of the escape to the realities we live in. That’s why we make art: to create new worlds worth escaping into.