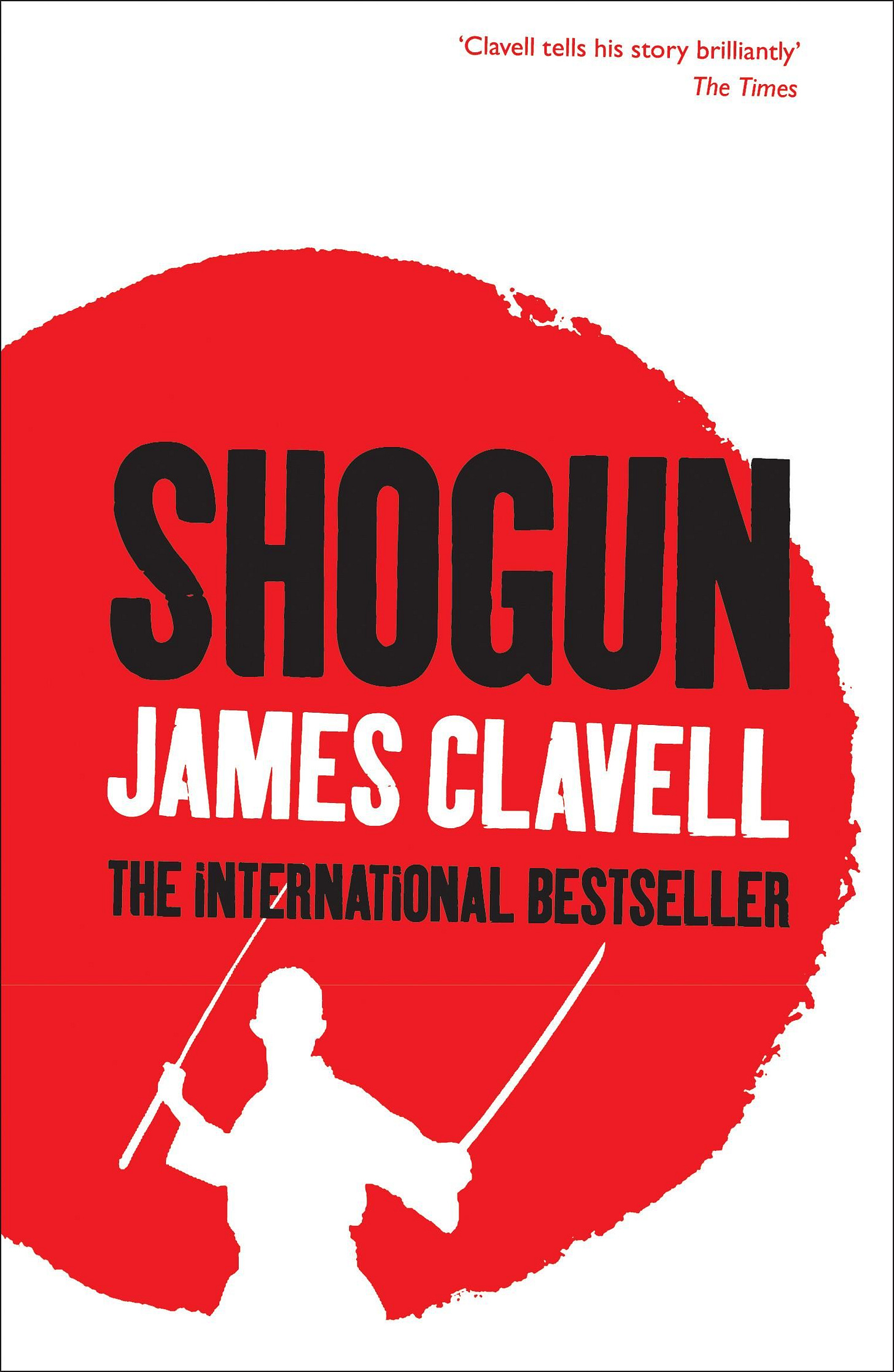

The 1975 James Clavell novel Shogun has, starting today, two adaptations.

Usually when I write about something like this for all you fine people, I secretly do a decent amount of research. Sometimes that means just watching a movie or TV show or reading a book, but sometimes it means quite a bit more.

Today, I did something a bit unusual for me in that I restrained myself from doing more.

See, we watched the 1980 miniseries adaptation of Shogun and then I just stopped and waited.

I picked up the James Clavell novel and I even read about 100 pages, but I decided to stop right there. I write often about adaptations because I find that process and the differences between mediums interesting. I watched the 1980 miniseries, was going to read the novel, and then I was going to dive into this new adaptation, with the result, here, being that I discussed all three in relation to one another.

But I stopped reading the novel and decided to just let the miniseries live on its own. And tonight I’m going to watch the opening episode to the new adaptation. Later this year, I’ll be reading the novel for the first time.

I have a longstanding theory that if you want to enjoy the adaptation of something, you should experience that first. Because adaptations rarely improve on the source material (more on this when I write about the live action Avatar: The Last Airbender), so you might as well give the adaptation the best chance it’s going to have.

In practice, I almost never do this. But I did it with Shogun, somewhat accidentally, so let’s talk turkey.

If you’re the type of online addict who’s asking why they included a white person in this show about Japanese history, you might be interested in knowing that this was based on the real life of William Adams, the first British person to land in Japan.

Set in the year 1600, on the eve of the Tokugawa Period of Japan, John Blackthorne is a British pilot of a Dutch trading vessel who successfully arrives in Japan.

The adaptation takes a fascinating choice to highlight this. Because this is set in Japan with an almost completely Japanese cast, most of the dialogue is in Japanese. And this spoken Japanese goes untranslated.

As in, there are no subtitles in the 1980 adaptation of Shogun.

Immediately, we have a bold choice with huge ramifications for the audience. A stylistic sledgehammer that immerses us deeply into John Blackthorne’s experiences in Japan.

One of the first people he meets is a Portuguese Jesuit who absolutely hates him and identifies him as an infidel. Again, the year is 1600. The Spanish and British thrones are imperial rivals and England’s reigning queen was the daughter of Henry VIII, the man who shrugged off papal authority so he could divorce and behead his wives. At the same time, Martin Luther set the theological world on fire and wars over religion split kingdoms apart.

And so priests are immediately pinned by the audience as enemies to Blackthorne. We also understand, from the priest’s use of Japanese, that they’ve established themselves in the power structure of Japan.

Through the twists and turns of fate, driven by the internal politics of Japan and Portugal, Blackthorne comes to meet the daimyo Toranaga, played by Toshiro frickin Mifune(!), and Toranaga takes a liking to Blackthorne.

He also provides Blackthorne with an interpreter named Mariko, who is also a Catholic. As time goes on, these two fall in love, and Toranaga must flee from his rivals, who wish him dead. The Portuguese want him alive and so they begin assisting Blackthorne, who saves Toranaga’s life and is thus made into a samurai.

The entire series, we understand the political situation through Blackthorne. Occasionally we come to know things he doesn’t know, but we are largely living with his knowledge of what’s going on. And this is incomplete, to say the least. He learns more and more Japanese, yet the subtitles never turn on to give us more clarity.

We must learn as he learns. His vocabulary is very limited and so we understand what he’s asking, what he’s saying to the Japanese, but then we and him must go by inflection, tone, body language, and hope that the person speaking to him uses the words he—and we—know.

Every now and then, a narrator allows the viewer to understand what’s being spoken in Japanese. The narrator is Orson Welles, of all people, but he is used so infrequently that we remain largely in the dark about the specific plans, unless Mariko or a Jesuit explains them to Blackthorne.

At the same time, we are never really confused. Which brings me to another stylistic choice that highlights how miserable filmmaking has become in the forty years since this was made.

In modern filmmaking, whenever we see dialogue, we do a close up on the speaker’s face while they speak and then we cut to a close up of the other person as they respond. We ping pong back and forth like this through the entire scene, until something breaks us out of this. We rarely, if ever, get a wide shot of both people speaking at the same time, and so we never really see body language or even how people respond to what’s being said in the moment.

Along with that, any scene of movement is full of so many cuts that we are constantly jumping around, seeing a scene from a dozen angles. Visually, the camera must always be in motion for fear that the audience grow bored.

But one potentially accidental outcome is that we rarely fully understand the geography of a scene.

Most of this is done to hide things. Either the set looks like shit or it’s all CGI in a warehouse or to mask the fact that actors don’t learn choreography and blocking anymore, or maybe directors just don’t know how to direct actors. Who can say! Maybe the fault lies with editors.

I’m not king of Hollywood so no one tells me.

But what we see when we watch movies and TV from the past is a steadier eye and hand. When characters are talking, we get a view of both of them. And we linger on them together, seeing one actor deliver lines and the other receive those lines simultaneously. We see actors move around. They stand, they walk or pace. In a word, they act.

They embody their characters and we are allowed to inhabit that embodiment by seeing them fully and uninterruptedly. When cuts happen, it’s usually for a practical or deliberate reason rather than fear of boredom.

This is not exactly a new observation. I even wrote about it last year.

who is to blame for why movies are terrible?

I sort of jokingly answered this question a month ago with my essay on Barbie, Marvel, and Christopher Nolan, but I stumbled across a very good essay that breaks down why most movies look and feel terrible now. Really, the whole essay is great and definitely worth reading as

But it is fascinating to see how idfferent this looks and feels. There was a moment when the camera observes Blackthorne, surrounded by samurai, walk from a prison to a palace. What my wife noticed is that all the samurai seemed to be walking in sync.

Such a little detail. Never does the show draw attention to it or even highlight it. But it’s there. You can see it.

And that tells us something about the samurai, about the rigidity of this society.

If that exact same scene were shown today, it would be handled very differently.

Even if the actors were told to walk in sync like that, the camera would cut so often that we’d never really get a chance to just observe this peculiar bit of worldbuilding. Or the camera would fixate tightly on this to ensure the viewer saw what the director wanted them to see.

And I think that leads to a very boring visual language. There’s a joy in discovery, even if all you’re doing is noticing a minor detail that has no impact on anything but your own understanding of the world.

The 1980 adaptation of Shogun is full of these choices, large and small, that pull us deeper into the world of 1600 Japan. By keeping us close to Blackthorne, the wily plotting of Toranaga also takes us off guard and surprises us. We understand how shrewd he is, yet we only see his hand at the very end, when he’s revealing it to the world, establishing the Tokugawa Shogunate.

And while some may wish that we’d been on the inside of his plotting, of his political jockeying, I think seeing it from this remove allows Mifune’s Toranaga to grow in stature.

We see and feel, bonedeep, the power of this figure and while he often seemed imperiled, his success, by the end, feels destined. Like it must always be this way. An inevitability to his rise.

It gave me chills when he revealed the man he truly was.

But what I’ll remember most about Toranaga, the character, is the ways the show revealed him in all his complications and messiness. Especially, I’ll always remember him dancing with Blackthorne in a private moment of levity.

I cannot recommend this miniseries enough, and while you can’t easily stream it, the bluray comes with all kinds of special features. And it’s nice to own physical media. Especially ones that make bold directorial choices.

The new adaptation looks like this and I cannot wait to watch it. It promises to be a very different adaptation of the book, with more perspective given to the Japanese players, which is apparently more true to the novel.

I just hope it remains bold.

My novels:

Glossolalia - A Le Guinian fantasy novel about an anarchic community dealing with a disaster

Sing, Behemoth, Sing - Deadwood meets Neon Genesis Evangelion

Howl - Vampire Hunter D meets The Book of the New Sun in this lofi cyberpunk/solarpunk monster hunting adventure

Colony Collapse - Star Trek meets Firefly in the opening episode of this space opera

The Blood Dancers - The standalone sequel to Colony Collapse.

Iron Wolf - Sequel to Howl.

Sleeping Giants - Standalone sequel to Colony Collapse and The Blood Dancers

Broken Katana - Sequel to Iron Wolf.

Libertatia; or, The Onion King - Standalone sequel to Colony Collapse, The Blood Dancers, and Sleeping Giants

Noir: A Love Story - An oral history of a doomed romance.

"I have a longstanding theory that if you want to enjoy the adaptation of something, you should experience that first."

This, and I personally deal with sources and adaptations as two different animals altogether. Great review.

Hmmm I sure am intrigued by the fact that there's a whole bunch of untranslated Japanese in the original miniseries. Makes me want to give it a watch and see how accurate it is, and what's being said! Sometimes, knowing too much about Japan(ese) can ruin these sorts of stories for a person, and sometimes it can make them more/differently enjoyable. In this case, I think it would add an interesting layer to the experience, at least.