Guest Post by Kyle Muntz. Pre-order his upcoming novel from Clash Books, which is set in the Midwest in the 2000s. I read an early draft of this novel and loved it. It’s creepy and funny and sometimes the body horror will make your skin crawl. Follow him on twitter or instagram (especially if you like food).

If you’d like to submit your own writing for a future Guest Post, please see the post here.

Is 15 years a long time? Today, as I approach my 32nd birthday, the question has never felt more ambiguous. I read a lot of history, and in those books, time is always passing; there’s a strong sense that everything is temporary and few things last, and periods which seem special are just the same historical forces arrayed in a slightly different way. But what about the subjective experience of our dumb, little lives? Because of course, for some of us, one time in particular shines much brighter (or darker) than the others.

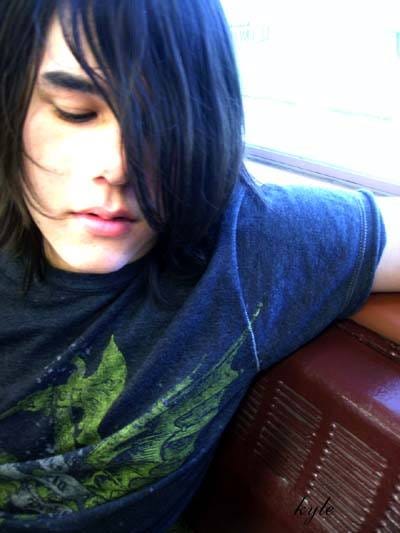

But was being a teenager everything that I remember? It wasn’t a happy time—mostly I was just emo as fuck, or I wanted to be. I stalked the waking world like a vampire disdainful of the light, reveling in my tight pants, long hair, and occasional experiments in wearing makeup. I passed whole afternoons blasting metal on my boombox; on weekends, I hung out at local hardcore or screamo shows at the only music venue in our little town. I wanted everyone to know that I was cool, not a part of all this bullshit, and every hint of doubt or derision only emphasized my metrosexual boldness.

But more than anything I was full of feeling. Sometimes it was hope—this powerful, visceral upwelling like a fountain of light. Others it was anger or ambition. Painfully intense love. Every experience was an important memory, every idea a revelation. My mind was opened when I first watched the right anime series, finished my first big literary novel, or crawled through my first tome of incomprehensible philosophy.

My insights, I knew, were both deep and profound, and would last forever, until I died some stupid, meaningless death in a future I had hardly begun to contemplate. At the same time, I suspect I believed I would never die, that the sheer energy of myself was so much it could never be extinguished. Everything seemed infinite: truth, beauty, pain. My heart broke and it seemed clear that I would never recover. But more than anything, I knew I would never become one of those lame adults I hated so much.

I also took pictures like this:

Or, on especially dramatic days, like this:

But most importantly, I was the lead singer of a band—and one day, I knew, we would become famous. Our music, I felt, was both revolutionary and profound; I gave the songs long, cryptic titles, and studded the lyrics with references to philosophy. I grew my hair and wore girl’s pants. Occasionally, I looked in the mirror and thought I was as lithe and sensual as a woman. But metal guys thought I was too feminine; rumors circulated about my sexuality, and none of them were spoken in the spirit of encouraging diversity.

Mostly I just got on stage and screamed. All our shows were in small towns—those people didn’t even listen to metal! But especially when they didn’t understand our music, I felt vindicated. It felt good to shock people: it seemed important, like I was fighting some kind of war. Against who? I’ve never known—I just felt that to be mainstream was practically a crime, and if I just found some other, different, more particular way to exist, it would all be alright. I would prove myself or win some kind of victory, and even if it was intangible, it would all be worth it.

But the body decays: time is a weightless, invisible mallet that smashes everything when we aren’t even looking. It’s hard to say when it happened, but even as my life became more well-adjusted and pleasant, it also changed in other ways. Increasingly, it seems those immense, powerful emotions that once exploded in me came from a place that just isn’t there anymore. In “Behave”, neuroscientist Robert Sapolski suggests the change is biological. Teenagers have stronger emotions and they really can’t control them, and it’s genuinely because their brains are different

Whether this is true or not, I suspect very few people believe it. We’re constantly doing stuff to regain the emotional intensity of our lost youth: going traveling to “find ourself”, switching lovers to “rediscover our passion”, hitting the gym to “feel young again”. Often the activities are new and different, but we miss that level of feeling: the glowing, beautiful awareness of being the center of something, that this moment is everything. So much of modern life is an attempt to slow the passage of time or pretend nothing has been lost—to undo that “distance” which somehow, unbearably, has grown up between us and the world.

But would I even want that intensity back, asks my weak, yet apparently existent rational-self? My teenage existence was crippled with anxiety. Each conversation with an unfamiliar person was its own gauntlet of fear; groups were worse, especially in new or disorienting places. Every word felt wrong. Every gesture felt alien. Life just felt so much easier, so much safer, when I was by myself, reading books—and maybe that was one reason I thought I hated people so much.

Today, I’m confident (correctly or not) that I can talk to anybody for hours. Sometimes I chat my way around a literary conference, a party, or a bar—who cares if I make a fool of myself? And often, when I see how much easier life has become, I’m grateful for the invisible machinery that has slowly installed itself in my head. These deeply embedded processes, or habits, or maybe I’d even call them “programs”, just take over as I pretend to be confident and interesting. Sometimes they even seem to do my talking for me. Probably they guide most of my behaviors on any given day.

So how do we occupy ourselves as the faint, shriveled husks biology has doomed us to become? I still spend tons of time reading books, and I often enjoy them, even if they aren’t the revelation they used to be. I still listen to death metal and it’s brutal as fuck. More recently my obsession has been cooking, which I post about like a maniac on Instagram—and there’s a good chance I’m a better cook than writer. Yet even as my life settles into an ever-finer balance, that sense of distance grows. Every moment feels lucid and clear, I’m in control—yet suddenly I pause, and realize months or even years have passed by, and where the heck was I all that time? Who had those experiences, and why do they already feel so far away?

The “projects” of an adult, like adding a new room onto a house or losing 50 pounds, give us something to do every day. They push away thoughts of death and provide structure (even purpose) to otherwise vapid or dumb lives. But what satisfaction lies at the end of these immense undertakings? In my experience, usually a brief euphoria, followed by feelings of emptiness and the immediate search for something else. Still, could I even live my life without erecting these illusory landmarks ahead of myself? Can anyone?

My guess is probably not. Every day I sink further into the comfortable enclosure of myself. So many of my most important decisions were made long ago; sometimes I’m just done with certain things. Every day, this person I’ve become lives his life in the only way that makes sense to him, driven by a force of habit so strong I could hardly imagine wanting to fight it. On rare occasions I glimpse the shadow of a future-self who is less adventurous, more uptight, and perhaps—worst of all—a little bit like my dad. But am I actually choosing to become this person, or is it just that invisible machinery grinding away? And does that mean I’m becoming more like myself, or less?

I honestly have no idea. The ghost of that emo teenager still appears some nights, and I know he doesn’t want to give in. But he stopped screaming a long time ago.

Being much older gives more insight as I've taught many emos and stayed in touch over years as change and self-awareness sets in. Am positive Dostoyevsky was an emo w/o electronic expanse.