Originally published in 2015 at Entropy.com which no longer exists.

2015 is the 30th anniversary of the founding of Studio Ghibli and, according to Hayao Miyazaki, it may also be one of its final years as a studio. Because this is one of my favorite films studios and Miyazaki is one of my favorite artists, who’s made some of my favorite films, I’ve decided to go through the history of Studio Ghibli one film at a time.

If you’re looking for the discussions of the previous weeks:

This does, however, mean I won’t be discussing Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, which was made before the founding of the studio.

I’ll also only be discussing the Japanese audio version of the films, though that doesn’t mean the dubs are bad or not worth seeing. They’re just slightly different. I’ll also be discussing these with the assumption that they’ve been seen by you. So, yes, spoilers are below.

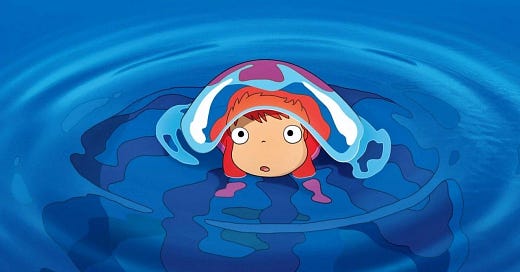

Hayao Miyazaki’s Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea, or just Ponyo, is a visual masterpiece. As a Miyazaki film, it’s not my favorite, but it does offer some amazing moments, some surprisingly big ideas, and just so much fun. It would best be described as a children’s movie, and is probably the most child oriented Miyazaki film since Kiki’s Delivery Service, but there’s also a subtle darkness to this film that really only exists if you take a step back and think about what you just experienced.

That’s the part that’s most interesting to me, but we’ll get to it later.

Ponyo is a retelling of The Little Mermaid, though with a lot of Miyazaki and Japanese influences. It begins stunningly. Those first five minutes where not a single word is spoken is so beautiful, so simple. The underwater world Miyazaki created is magical, beautiful, natural, and effortless. Immediately, it gives us a lot to look at, puzzle over, and just smile about. And sometimes we’re doing all of those things at the same time.

The environment is a character in the film and we quickly see one of the conflicts of the film. Ponyo is captured in a fishing net, which is drudging up all kinds of garbage humans have spilled into the ocean. She escapes the net stuck in a bottle only to be discovered by a young boy named Sōsuke who takes her ashore, drops her in a pale full of water, and gives her the name she’s known for. In bringing her ashore, the ocean waves rise to take her back and her father comes ashore, spraying the ground with ocean water to keep himself from drying out.

It’s one of the most awesomely peculiar moments in any Ghibli movie. Watching this redhaired man dressed so oddly using some kind of pumpsprayer to keep the ground wet while he walks around on land.

Lots of adorableness follows, with just great animation, and then some adult moments indicating at least a bit of marital tension between Sōsuke’s parents. This film gets closest to the wide eyed wonder of being a child better than anything besides maybe My Neighbor Totoro. The way Sōsuke runs away from people when he thinks they’ll get him in trouble. The way he hides and covets Ponyo. It’s so utterly fantastic.

The film is kind of impossibly gorgeous but one of the best animated moments, I think, is watching Sōsuke walk down the stairs to hide from his mother while carrying the pale that holds Ponyo.

Anyrate, the ocean does rise to take Ponyo back to her father, Fujimoto. He’s the redhead with funny clothes. We also discover Ponyo’s real name, Brunhilde. Fujimoto is mostly concerned with keeping nature and the world in balance, which he does through magic and potions. Keeping Ponyo in the ocean is also an important aspect of this, but Ponyo desperately wants to be human and be friends with Sōsuke. Fujimoto manages to keep her trapped and reveals that he was once human before giving himself to the ocean. He worries for Ponyo because she’s now tasted human food and the blood of a human, and she’s young but incredibly powerful and will soon be too powerful for him to control.

Ponyo’s sister’s break her out and also disrupt the balance of the world. Ponyo transforms into a human, creates a tsunami, and finds Sōsuke once more.

It’s a moment of elation and beauty. We’re thinking that Fujimoto is being an overprotective dad or just kind of a jerk, so Ponyo’s escape is invigorating, in part because she causes an insane flood just to get to Sōsuke, which sort of softens once they’re reunited. The ocean still roils but it’s no longer rising.

More adorable childness follows and these moments are so great. Ponyo, Sōsuke, and his mother weathering the storm. Ponyo’s delight in everything is infectious. Using her new body, touching, tasting–everything amazes Ponyo. Watching her play with Sōsuke, eat, and run around is just great, and the animation is beautiful.

I mean, this kind of stuff is hard not to just absolutely love, even if you hate animated films or anime in general or just movies about kids made for kids, or even if you’re some sort of heartless monster unable to believe in magic.

Sōsuke’s mother runs back to town to help the elderly at the center she works at, leaving the children alone. Then here comes the goddess of the ocean, in all her power, majesty, and terror. Meanwhile, Fujimoto just can’t catch a break. His daughters keep defying him, his lover starts spilling magic all over the place, and Ponyo has become a human.

Fujimoto and the goddess of the sea talk about their daughter, the balance of the planet, and its seeming imminent destruction, but the goddess decides to put their child and Sōsuke to the test. The world and Ponyo’s life literally hang in the balance, and the goddess wants to see if Sōsuke and Ponyo’s love is pure enough to turn her human forever, which will rebalance the world. If they fail, however, Ponyo becomes seafoam and maybe the earth is permanently thrown out of balance, ripping satellites and the moon from the sky.

So, yeah, despite the adorableness of everything, the stakes are shockingly high.

Ponyo and Sōsuke wake to the ocean at their door and Ponyo uses a bit of magic to turn a toy boat into a real boat that they can ride, which is adorable and funny and fun. Ponyo is literally an out of control insanely powerful monster, but she just wants to play with Sōsuke. Her power waxes and wanes, though, and all her magic stops working once she gets sleepy, which she’s prone to doing. It’s all quite awesome to watch, but it’s understandable that Fujimoto is seriously concerned.

Fujimoto is protecting humanity underwater with these kind of giant bubbles of magic. This is also the site of the Sacred Test of Love between Sōsuke and Ponyo.

As Ponyo and Sōsuke approach, Ponyo’s sleepiness causes her humanness to gradually fade until she’s the little water creature we first met, leaving Sōsuke alone in a drowned world where Fujimoto finds him.

He tries to lead Sōsuke away in kind of the creepiest way possible, which isn’t surprising since he’s an odd looking creep. In his desperation, he starts losing it, because the moon is literally on its way to crash into the earth, so Fujimoto ends up taking them rather dramatically to the Sacred Test of Love under the ocean.

Sōsuke and the goddess discuss the actual future of the planet and whether or not it will survive, with all of it depending on the love of children, which is a love so pure and profound that it transforms Ponyo into a human permanently.

And so the world is saved in the cutest way possible.

It really is a beautiful film in every way, from characters and story to animation. It holds onto its childishness with gorgeous magic and the love children share without even trying.

The goddess leaves, restabilising the planet.

Life begins again, as she says.

But let’s talk about those other elements. The ones underneath or at the edges of the film that really make this something more than a children’s tale.

I’m talking about Fujimoto, who is, I think, one of the most interesting characters Miyazaki’s ever created.

Fujimoto began life as a human. It’s unclear what happened, but something caused him to give his life to the ocean. Likely, it was that he fell in love with the goddess of the ocean. This turned him into a sort of ocean god. His responsibility is, simply, the world’s balance, which is no easy task when you consider Ponyo’s behavior and the behavior of her many sisters. His war is against humanity’s pollution, which we are forced to confront very early in the film and then a few times throughout. This has turned his heart against humanity, despite being once one of us. He hates humans because we spoil the earth, we flood the seas with garbage, and we kill habitats and species by the thousands through our carelessness.

I’m not much a fan of us when I think about this either.

Look at this beleaguered weirdo.

But Fujimoto must deal with it every day. He must fight against the pollution with his magic, to keep the earth balanced. Because he’s not a native to the ocean, his power seems considerably less than that of his lover or their daughters.

His lover is the goddess of the ocean, the Mother of the Sea, as humans name her. It can be assumed that he fell in love with her and that she loved him. It can further be assumed, I think, that he chose the ocean and her over the world of land. In this way, he and Ponyo went on parallel journeys in opposite directions. Ponyo gave up the ocean and magic for love. Fujimoto gave up his humanity and his life for love.

But what is his love?

To me, it’s a sorrowful, lonely kind. His lover, the Mother of the Sea, is often away from him, and he longs for her. He misses her, and it breaks him, but he must keep the balance, raise their daughters, and keep the world going. In many ways, it appears that his lover has abandoned him and isn’t especially concerned with his well being.

We see this in the single scene they share. He opens his heart and concerns to her and she just kind of waves them away, then ignores him for the remainder of the film.

His concerns are valid, I think, on a few levels. For one, he is Ponyo’s father. Ponyo is still very young and he fears she doesn’t understand the choice she’s making. Further, she’s choosing what he ran from. She’s choosing to be human, which is something he hates and fears and fights against every day.

However, because of the perspective of the film, he seems almost like an antagonist. He wants to trap Ponyo and deny her freedom. When she escapes, he expends a lot of energy to take her back. Even when he goes to take Sōsuke and Ponyo to the Sacred Test of Love, he comes in a way that is sort of frightening, especially if you’re a young boy trying to save your best friend who you just watched transform from a human to a sea creature.

Fujimoto is essentially a single working father trying desperately to do his best, but he’s so overworked and spread so thin that he can’t really reconcile what he knows with the desires of his daughter.

In some ways, this is even reflected by Sōsuke’s mother, who is going through some difficulties in her marriage, due to the fact that her husband must spend a lot of time away from her and Sōsuke.

In Fujimoto we have a very complex character whose entire story is only briefly alluded to and he remains on the periphery, seen by many as mostly a narrative obstacle. And even in his life, he’s shoved to the side by his lover, the Mother of the Sea, the ocean itself. He is a man caught between the infinite and the mortal, between creation and destruction, and he is floundering.

This is the kind of power Miyazaki has. In just a few minutes of screentime, he creates Fujimoto in whole. He’s a footnote on Ponyo’s story, but his own is one of tragedy, sorrow, and infinite love for those who seem to ignore him. Even his hatred of humanity is because of his love for them. He keeps the balance of the world for their sake too, but they continually fight him over it. He sees them as a species racing towards destruction, and their destruction will, unfortunately, also destroy the planet by careening it off balance.

There’s no antagonist here, much like all of Miyazaki’s films. Rather, there is a complex relationship of power being explored.

Fujimoto, Ponyo, Sōsuke, and Sōsuke’s mother are all heroes here, but Ponyo and Sōsuke are highlighted, pushing the others to the sidelines.

Miyazaki creates a fun, adorable, and beautiful film for children, while also packing it full of big ideas and real concerns. He’s giving us the complexity of family, the intersection of environmentalism and capitalism, the power of love, and what it means to be a child in a world balancing precariously on life and death, where every choice resonates through the global ecosystem.

So Ponyo is not my favorite of Miyazaki’s films, but it might be his most masterfully subtle and complex.

On the surface, it’s a simple family film, but this film is deep as the ocean. Once you look past Ponyo, you begin to see an immense world of huge conflicts that have no easy solutions.

What you have is one of the most powerful and complex films about family, love, and the environment made in the last decade. And it’s meant for children and children will love it.