Originally published in 2015 at Entropy Magazine.

2015 is the 30th anniversary of the founding of Studio Ghibli and, according to Hayao Miyazaki, it may also be one of its final years as a studio. Because this is one of my favorite films studios and Miyazaki is one of my favorite artists, who’s made some of my favorite films, I’ve decided to go through the history of Studio Ghibli one film at a time.

If you’re looking for the discussions of the previous weeks:

This does, however, mean I won’t be discussing Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, which was made before the founding of the studio.

I’ll also only be discussing the Japanese audio version of the films, though that doesn’t mean the dubs are bad or not worth seeing. They’re just slightly different. I’ll also be discussing these with the assumption that they’ve been seen by you. So, yes, spoilers are below.

Pom Poko is maybe the strangest thing for Takahata to make after Only Yesterday and Grave of the Fireflies. Those films are pure realism, subdued, and deal with very real emotions and situations and humans. Pom Poko, on the other hand, has almost no humans in it. It also deals with very different kind of emotions. It’s sort of an antihuman film. It shows us the emotions of nature and what the world must do to adapt to us.

The perspective taken is that of the Tanuki, or raccoon dog. These are significant to Japanese folklore, representing shapeshifting tricksters, similar to Kitsune (foxes), but less devious, I suppose, and much gentler and simpler in nature. They’re absent-minded and easily distracted. In the subtitles, they’re only ever referred to as racoons, but they’re meant to be more than that.

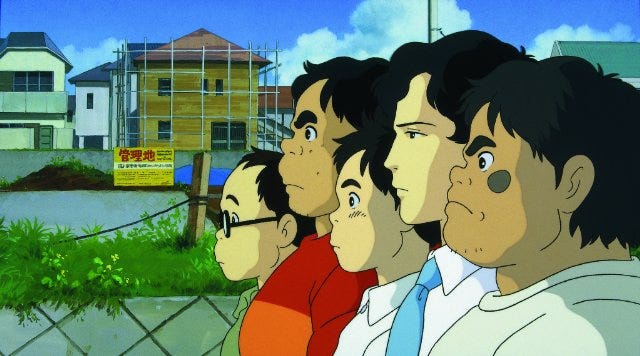

I suppose it makes a bit of sense to take this direction. Only Yesterday is full of commentary about how humans should behave in nature and treat the natural world, so maybe it’s not so strange for Takahata to take up that perspective for an entire film. Pom Poko mostly deals with the urbanisation of the Japanese countryside and human expansion into natural habitats of other creatures. The tanuki watch as their forests are destroyed, the hills flattened, and human made structures rise into the air, blocking the scenery. They watch as the world they’ve known for hundreds and maybe thousands of years is transformed in just a matter of months. In this film, humans are the force of nature and destruction that the characters must work against.

And so, of course, they decide to wage war.

Before we get into that, I want to comment on a few things about this film.

Where Grave of the Fireflies and Only Yesterday were quiet films where we could live in and experience that stillness and silence, Pom Poko is an incredibly chatty film. There’s barely a breath without speech. Much of this is done in rapidfire narration. A handful of the tanuki narrate this film and they speak fast. So fast that you can’t even really look away from the screen or you’ll miss something. It’s such an odd choice, for a lot of reasons, but for a man who makes such elegant and beautiful and quiet films, it seems both out of place and sort of destructive. There’s so much narration that we lose all the beautiful moments he does so well. There are no scenes where we just get to observe behavior and learn to love the characters. There is only narration.

It flattens out the film and the characters. We never really get to know any of them very well or in a significant way. A few characters stand out but not because we come to learn their traits and behaviors. They stand out because they’re stock characters that’re easily identifiable.

And so we see them.

This lacks the attention to detail and the Ozu-like style of filmmaking that makes Takahata so great. It’s replaced by something that feels much more intrusive and childish. Takahata doesn’t trust his audience to keep up with the narrative or he’s doing this out of laziness. Because, really, there’s no reason for there to be so much narration. The film is two hours long, which is pretty substantial for an animated feature, and we have probably 110 minutes of solid voice over narration. I’m not convinced we needed all that or that the narrative needs it.

In some ways it adds a sort of wistfulness to the film or a sense of nostalgia in the narrators, but I think it mostly harms the film and holds it back.

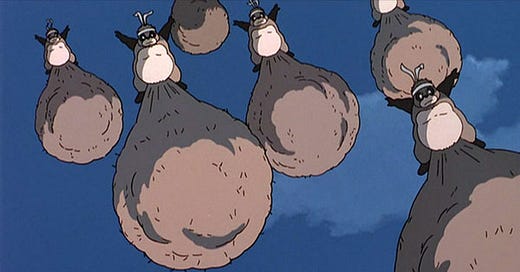

The next thing is the animation, which I actually like a lot. As seen in the image at the top of this article, the tanuki sometimes appear as anthropomorphic creatures. This is almost exclusively when they’re amongst one another. When they enter the human realm or come into eyesight of humans, they take on a more naturalistic look, more reminiscent of Takahata’s style in his previous films. Then there’s a third style that happens when they’re in the throes of silliness. It’s a kind of cartoonish anime style.

I like this element a lot, oddly. It shows a separation of worlds, a separation of myth and magic and the reality constructed by humans. To humans, they’re just odd little beasts, while, in their own reality, they’re powerful forces of nature! Sometimes they’re very silly and lazy creatures that just want to drink and play and dance and sing.

But back to the war.

The tanuki decide to take advantage of their ability to shapeshift and resemble humans. This is the tool they use to combat humanity’s endless expansion and the destruction of their habitat. The older tanuki train the younger and eventually we have a lot of tanuki who can resemble humans and remain in that shape for extended periods of time.

So what do they do with this power? Well, naturally, they just cause trouble.

They sort of haunt the humans, bringing to life age old folklore in the people. Construction workers boycott out of fear. With every celebration, though, comes complications. Though many leave the job, they’re quickly replaced by new humans who need to make a living.

One of the tanuki advocates for killing humans. It’s hard to remember what his name was because most of the film happens in narration and none of the character names seemed actually important, though this character is a standout. At one point he even causes a coup among the tanuki to try to get them all to wage violent war against the humans.

This coup falls apart quickly, as the tanuki are mostly concerned with what to eat, so even his carefully chosen soldiers become distracted and careless. I mean, this coup literally lasts about five seconds. But this fits with the folklore of the tanuki.

Some humans do die, though. Some of the tricks they play are a bit more fatal while many more are mostly to instil fear in the workers and new inhabitants of the housing development.

The tanuki are literally fighting for their lives here, but the stakes never hit us because we never really come to know any characters.

There are even deaths among the tanuki, and these should hit hard, but, again, we barely know them, so they sort of roll over us and wash away. Each tanuki dead does very little for the viewer, sadly.

But the tanuki are so devoted to the war effort that they even abstain from procreation…for a while. They do this because the more tanuki there are, the less food there is to go around, especially with their ever shrinking habitat.

Things become so dire that they beseech shapeshifting masters to aid them. These ancient tanuki come and they wage one last valiant effort against the humans and the housing development.

A demon parade! They use their shapeshifting powers to create a truly supernatural spectacle for the humans, with the aim to drive them out with fear. The world of demons and magic and legends comes alive and includes a fox marriage and many other spectacular sights.

One of the ancient tanuki masters dies in this effort and they mourn his loss while they celebrate their achievement. They turn on the television and watch the news where they see their success. The humans are afraid and no one has any answers for this amazing phenomena.

All of this falls apart when an amusement park scheduled to open takes credit for the event.

With that, all hope seems lost.

And, really, that was their final moment of glory.

They lose the war, but through their meddling and tricks, they gain a bit of an audience among the humans. Or rather, the humans believe in them, and so leave small parks for them to live in. They want the legends and folk tales to live on with them.

Unfortunately, this concession isn’t enough, as the parks are too small for them to live in and survive.

What do they do?

They give up. They give in.

They live as humans. They shapeshift and remain in their human forms for the rest of their lives, where they must exist as humans do. Riding trains, going to work, making money–they must deal with all the stress of Japan’s modern life while pretending to be human.

And that’s more or less the end.

Humanity wins in its destruction.

It’s a very dark film while also being mostly a comedy. It’s an oddity, to be sure. I like it a great deal more than Porco Rosso, but it’s just as odd for this film to exist. Though, Pom Poko does go a lot deeper and say much more about humanity. It’s an indictment, really. He’s pointing a finger at us and yelling for us to stop this nonsense, this senseless destruction of the world around us.

But, like the tanuki, he’s too little and he’s too late. Nothing can stop our thirst for more. Our lust for transformation.

Pom Poko has a lot of problems, but it’s still a solid film. I think there’s a lot to be gained from seeing it, but this is surely the strangest time in Studio Ghibli’s history. I’d even call it a low point, but I may be alone there. I mean, this was the number one film in Japan for 1994. It was also Japan’s selection for Best Foreign Film at the Academy Awards.

So maybe you’ll love this film a great deal.

I’d recommend it, but not till after you’ve seen Takahata’s previous Studio Ghibli films, which are, I think, real masterpieces.

Next week we discuss Whispers of the Heart, the first Ghibli film not made by Takahata or Miyazaki.