Originally published in 2015 at Entropy Magazine.

2015 is the 30th anniversary of the founding of Studio Ghibli and, according to Hayao Miyazaki, it may also be one of its final years as a studio. Because this is one of my favorite films studios and Miyazaki is one of my favorite artists, who’s made some of my favorite films, I’ve decided to go through the history of Studio Ghibli one film at a time.

If you’re looking for the discussions of the previous weeks:

This does, however, mean I won’t be discussing Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, which was made before the founding of the studio.

I’ll also only be discussing the Japanese audio version of the films, though that doesn’t mean the dubs are bad or not worth seeing. They’re just slightly different. I’ll also be discussing these with the assumption that they’ve been seen by you. So, yes, spoilers are below.

Only Yesterday is a beautiful and seemingly simple film, but that simplicity contains a lot of complexity. It’s straightforward, but in telling it straight it makes room for a lot of complexity as well. There aren’t big emotions but complex and difficult ones. There’s little narrative movement, but those small steps of progression are more similar to a glacier, in that a little movement can mean a great deal for the shape of the world to come. The film is sort of built around such moments. How something from twenty years before can keep resonating across time and shape the moment we’re now living in. By shifting between Taeko’s childhood and present day, we can see how certain moments never leave her, and they remind us of all those little things we cling to from so long ago.

It’s significant to look at which things she remembers. Most of them are embarrassing or unpleasant, or, if not unpleasant, can easily be seen as a negative. There are happier moments in there too. Moments when she feels proud or loved, but many of them illustrate beliefs about herself she holds deep inside.

She’s 27, unmarried, living alone. If this film took place in the west or took place in the world of 2015, it might be less significant. But this film takes place in Japan in the 80s. There are cultural elements that make certain things much more significant in Japan than they may seem now. For example, Japan is still extremely patriarchal. And while that’s true of every country in the world, it’s more pronounced in Japan and certain other east Asian countries.

She remembers when the nurse told the class about menstruation and the road of life they’re meant to follow: school, graduation, motherhood. We would laugh at such things now, but this is still very much felt in Japan. For an in depth look at this, The Guardian did a story about how Japanese people seem to not even be having sex anymore, and there’s a general disinterest in it. Something the author of that story touches on is how a woman can be fired after she marries a man because the expectation is then that she’ll get pregnant and have children. And that is from the world we live in today. This film takes place about thirty years ago and was made twenty years ago.

When Toshio’s grandmother asks Taeko to become his wife and stay on the farm, Toshio’s father mentions how Toshio is younger than Taeko. This is one of those things that doesn’t mean much to us here but would be significant to a woman in the 80s in Japan. When I lived in South Korea this was also a problem for women I knew. One of my coworkers was dating a man several years younger than her and my other coworkers simply didn’t talk about it. If they did talk about it, it was always through a lens of shamefulness or idiosyncrasy. While South Korea is not Japan, this matter of age is still significant. Women aren’t meant to date or marry those younger than them.

I mean, none of these things are rules, mind. They’re more cultural norms or sort of implicit guidelines. I only mention them to give more context to the film.

Anyrate, many of her memories sort of reinforce this idea that she holds that sets her apart from most other people. She’s simply different, and sometimes she sees this as a big hindrance. Taeko, in some ways, wants to be like the other girls. She thinks her life would be easier or better if she could more easily follow the rules or do what she’s told. She sees her independent nature and willfulness as something that sets her apart from the rest of humanity, and not always in a good way.

However, I think the film shows this to be an asset.

But that last point doesn’t really matter. This is an extremely interesting follow up to Grave of the Fireflies. It’s very grounded in reality and behavior, which makes it similar, but it’s also a decidedly lighter subject matter. Both are very subtle films but this film is far more relaxed. It’s more about breath and space, beauty and longing, regret and choice. Grave of the Fireflies doesn’t have the time to contemplate on such things. While also being a film about choice, it lives in a very different dimension than Only Yesterday.

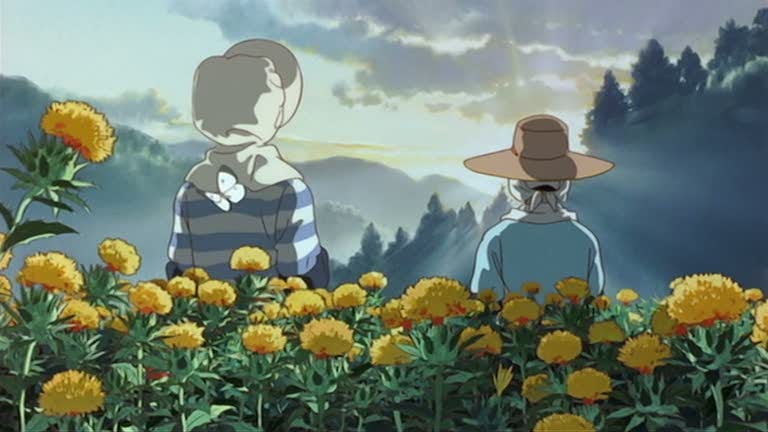

The two are almost incomparable, which is part of what makes them so interesting together. Takahata brings us to the very depths of emotions and humanity with Grave of the Fireflies. He creates a perfect tragedy that lives forever. With Only Yesterday, he’s allowing us to walk casually through nature. But while we walk and enjoy the scenery, he questions us and the world we live in and how we live in it.

Though this film isn’t really about farming or the environment or ecology, he certainly has a strong opinion about them. He doesn’t beat us over the head with these ideas, but he does present them. Toshio is an organic farmer, which is sort of a buzzword now, but wasn’t back then. In a sense, he’s a return to the traditional way of life. A life that exists within nature. He talks about how humans shape the land for themselves but all of this subtle terraforming depends on the planet itself. We can only exist at the grace and kindness of the environment, which is partly why Toshio chooses to be an organic farmer.

It’s also significant that Taeko is from Tokyo and has lived there her entire life. Even her parents have always lived in Tokyo. She’s a city girl, thoroughly. As a girl, she envied those who got to escape the concrete and buildings and roads by going to their ancestral homes in the country, and so she tries to recreate this as an adult. Her sister married into a family of farmers but they both live in Tokyo. Taeko, however, goes out to her brother-in-law’s home in the country to farm for her vacations.

There, she finds beauty and peace and something like home.

She comes to love this simple way of life and, in many ways, discovers that she may want to give up her life in Tokyo and join this older way of life.

This simple transition is also where the weight of the film is.

Everything here is about choice. All of her memories are about choice. She regrets based on the choices she did or didn’t make. She remembers fondly based on the choices she did make.

It was odd how much time the film spent on how a young girl responds to discovering that she’ll menstruate, mostly because I don’t think I’ve ever seen a film deal with that moment. I’ve definitely never seen an animated film deal with it or even mention such a thing, but Takahata gives us a surprising amount of time devoted to this topic.

But the thing is, it’s not really about getting your period or buying special underwear or even boys looking up their skirts. It’s about how we respond to change and new experiences. Rei, who’s sort of shown as a kind simpleton, gives her the perfect answer to all of this, though. While the other girls, who are more popular or well liked or smarter, lash out at the boys and try to defend themselves from their inherent shame, Rei just laughs off the immaturity of the boys and the girls. She takes on the change with a smile and when the boys try to shame her for having a period, it just rolls off her.

Because she doesn’t see any shame in changing. She doesn’t feel shame for developing.

So while the girls in class certainly hold her in relatively low regard, she’s perhaps the most mature and capable of all of them in dealing with life and its constant state of flux.

This portion of the film ends shortly after Rei accidentally teaches Taeko this lesson, because, really, all these moments of the past are combining to teach us how Taeko became who she is.

And Taeko often reminds me of Rei. She’s cheerful, simple, and takes much of life in stride. Or at least she tries to.

It matters that she holds onto her shame and regret, but it’s also clear that she’s come a long way.

Through failing often, she’s come to be a relatively well rounded person.

She accepts her role as an outsider. Though these moments and differences will always tug at her, she finds a sense of peace, and I think she discovered the strength to do so in Rei.

This film is about life and how minor currents or waves can reverberate across time and change the way we live and perceive reality. It’s brilliant and perfect in this way.

It’s a very subdued film and reminds me of the best of Yasujiro Ozu. It’s hard for me to not see his influence on Takahata between these first two films he did with Ghibli. How quietly passionate they are. How much they say while showing very little. I think my metaphor of the glacier above is quite apt for both of them.

They’ll show you a moment that at first seems simple. But that simple action carries the weight of lives within it and the shape of lives to come.

It’s very difficult and very subtle filmmaking. If anything, I think Takahata manages to do it better. He may not be as subtle, but his films are more watchable. I mean, I love Ozu and would happily watch his films every day, but I imagine few people really feel that way after watching Tokyo Story, for example. With that level of subtlety comes a lot of stillness and silence.

Perhaps that’s the main difference. Takahata is a much chattier filmmaker, which works quite well here.

He throws a lot of discussions into the film about a variety of topics. While none of them are really about the narrative, they keep us interested and entertained.

He can get away with that because, ultimately, Takahata is most concerned with characters. He cares about people and so his films shine brightly on his characters. The narrative is about their interactions more than it is about getting from point A to point B.

Summarising the action of this film is simple: A woman takes a vacation in the country where she rethinks her future.

Summarising the miles of emotions and thoughts is incredibly difficult.

That’s the power of Takahata here. It’s more difficult and less casually enjoyable, but infinitely more rewarding for those willing to give themselves to his film.

Because this really is one of the strongest Studio Ghibli films and I can’t believe this is the first time I’ve ever seen it.

Next week we discuss Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso. I’m hoping I like it a great deal more this time around.

Before we go, I want to say a few things about Studio Ghibli’s animation.

What interests me most about Studio Ghibli’s specific aesthetic is how clearly it influences anime in general while remaining almost completely separate from it. Miyazaki and Takahata have their own distinct styles and I think it’s clear that Miyazaki’s style is the one most imitated, but even Miyazaki’s style is very different from most anime.

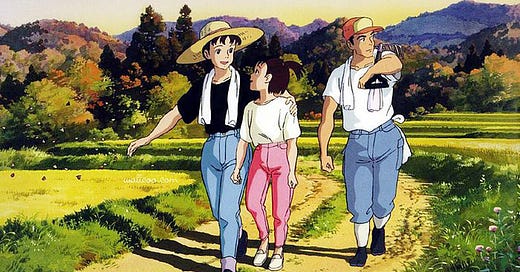

Miyazaki and Takahata draw people differently than just about any other animators. They’re probably the most realistically animated humans you’ll ever encounter. They’re proportional and their movements are extremely fluid. Really, you won’t see this kind of fluidity in any other hand drawn animated film.

While western animation is generally more realistic than anime, it still remains very cartoonish. Sure, many Disney films reflect how real people look, but only with the main characters. Aladdin and Jasmine have generally humanistic proportions and figures, but no other character in the film does. And even calling Jasmine realistic is kind of pushing biology and physics.

The same is true of most anime. Characters resemble humans but they don’t really share anything beyond that. There are the giant eyes, the impossibly thin waists and limbs, and typically the woman are hypersexualised versions of reality [though this varies widely, depending on the genre].

But Miyazaki and Takahata stay removed from all these conventions. Perhaps most significant, the women in their films are actually shaped like real women. This is undoubtedly anime, but the eyes aren’t enormous or disproportionate and neither are the limbs. Even the monsters and so on remain realistic in their depiction, strange and absurd as that may sound.

It’s an interesting place to land in. Being two of the biggest names in anime, influencing generations of animators, but very few of their imitators or artistic descendants look anything like them.