Originally published at Entropy Magazine in 2015.

2015 is the 30th anniversary of the founding of Studio Ghibli and, according to Hayao Miyazaki, it may also be one of its final years as a studio. Because this is one of my favorite films studios and Miyazaki is one of my favorite artists, who’s made some of my favorite films, I’ve decided to go through the history of Studio Ghibli one film at a time.

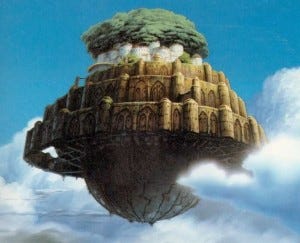

For the next twenty weeks, I’ll be discussing a different Studio Ghibli film, starting with Laputa: Castle in the Sky, which is the first Studio Ghibli film.

This does, however, mean I won’t be discussing Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, which was made before the founding of the studio.

I’ll also only be discussing the Japanese audio version of the films, though that doesn’t mean the dubs are bad or not worth seeing. They’re just slightly different. I’ll also be discussing these with the assumption that they’ve been seen by you. So, yes, spoilers are below.

Laputa: Castle in the Sky begins somewhat chaotically. A young girl being held captive on an airship struggles for freedom while airpirates attack the ship in order to capture her.

And in the process, the young girl knocks out one of her captors, steals back her necklace, and falls out of the airship to avoid pirates, plunging towards the earth.

The world of Laputa is a steampunk alternate reality with touches of magic, hyper advanced technology, piracy, espionage, and powerful militaristic governments. References to Jonathan Swift, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Hindu and biblical mythology made throughout the film tie this directly to our world. Many of Laputa’s themes will be seen in future Miyazaki films, which tend to deal with the real world, though influenced and refracted by magic and mythology and worlds hidden within ours.

While Laputa is certainly a world imbued with magic, much of the first half is firmly grounded in reality. The girl who falls from the sky is saved by the power of her necklace and she’s found by Pazu, a young orphan in a mining town.

And this, to me, is where things become very interesting. While the film contains magic, governments, armies, apocalyptic technology, it deals with real people. Not only real people, but average people. Pazu, one of our protagonists, is a miner and a child. Though the mining town is shown as a happy place with a strong sense of community, it reveals that this is an unkind world. Orphaned and working in a mine, Pazu becomes the unlikely and accidental hero in a story dealing with global consequences.

And our other protagonist, the young girl, Sheeta, is also an orphan with little idea about why she’s being pursued or why her family heirloom matters so much to so many people, and why they’re willing to kill for it. On her journey, she discovers the answer to these questions, but like Pazu, she becomes a heroine accidentally, with no interest in changing the world or fighting powers far too large for her to expect success.

And the introduction of Pazu isn’t the end to Sheeta’s problems, but only a coincidental meeting between two powerless children. Though Pazu is indeed heroic, he doesn’t work as a savior here. Sheeta may be a damsel in distress, but she has a real sense of purpose and very much becomes the heroine of her own story.

Though these two are pushed and pulled around by forces larger than themselves for much of the film, they both find courage and agency, determining not only their own fate, but the fate of the earth and human civilisation. Pazu and Sheeta collaborate with one another to combat the grand forces at work in this world.

Along with them, the pirates who begin as such a menace become heroes in their own right, led by their courageous and chaotic mother, Dola. Though a woman among pirates, she is their fearless leader, the one who takes responsibility, who leads the charge, who protects her clan.

Like many Miyazaki films, woman are important characters, and not only as complements to the men or to build up or play off the men, which is typically their role in film. In Miyazaki’s films, woman are strong, powerful, have a sense of purpose, and don’t need a man to save them. Often, they’re the ones doing the saving. And Laputa is no different. Dola and Sheeta are big forces in this film, shaping the narrative and battling against the men who stand in their way.

Laputa is about ordinary people, even criminals. This is a world that’s driven many to piracy in the air, much like imperialism and colonialism led to piracy on the seas. In addition, this is an industrial world where children are forced into the earth to hack out minerals and then pull them back to the surface.

All of this exists beneath the legendary castle in the sky.

As Sheeta discovers who she truly is, she also comes to understand the burden of her people. As a child, her grandmother taught her spells for a variety of circumstances. Their purpose only becomes apparent when she learns that she is the rightful heir to the Laputan throne. With this new knowledge, she stumbles into the first Laputan artefact besides her necklace: a giant broken robot.

And in discovering this robot, she accidentally sets it in motion, releasing a wave of chaos and destruction. As the robot rages, she finds a softness to it, and comes to understand that it responds to her, that it is her servant, that it may be more than simply a robot. And in this realisation, she watches as the robot is destroyed, her necklace taken, and hope once again taken from her as Muska, the government spy, our antagonist, heads to Laputa to control its power.

But let’s talk about Laputa, that hidden castle in the sky, the mythological kingdom everyone in the film is racing to exploit and plunder. It’s an ancient city with technology that surpasses even what’s possible today, full of giant robotic warriors, magic, and weaponry with the ability to destroy entire civilisations. It’s even credited with annihilating Sodom and Gamorrah. And while this power still exists along with Laputa, the city and kingdom itself, it’s been gone for hundreds of years and has become the thing of legend.

And 700 years go by from the last time Laputa has had any contact with the landed civilisations.

But what happened to Laputa? How did it go from an almost godlike world superpower to a mere legend, believed by few? This is a question that circles the core of the film but never really gets discussed or explained. It reminds me of Easter Island, where we discovered the remnants of an advanced society with no clear explanation as to why they’re no longer there or how they were able to construct those heads.

When we finally land on Laputa, we see some rather surprising things. The castle has become overgrown, with an enormous tree growing out of the island in the sky and through the castle. Perhaps most surprising, Laputa is empty of humanity. Only our remnants remain there. The structures we built and even the robots persist.

The robot we discover on Laputa is identical to the one that created all that chaos previously, but this one has a gentleness to it. It’s a gardener, taking care of the plants and animals that still live on Laputa.

Laputa is literally covered in life. Animals run and fly about the island. Plants grow everywhere, even over the robots built by humanity so long ago. Then there’s the giant tree of life at the center of the island that runs through the castle and core of the island.

And it’s here that we see Miyazaki’s environmentalism and pessimism most clearly. These themes are developed more clearly in future films and in Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, which precedes this film, but Laputa gives a stark contrast to the beauty of nature and the awfulness of humanity.

Humanity created Laputa and used it purely as an instrument of destruction and power. They used the awesome force for selfish and destructive purposes, conquering the world and lording over it. Without humanity, Laputa becomes a haven of nature, beautiful and tranquil. The robots built for murder and destruction become caretakers of life, allowing it to flourish.

This is where Miyazaki becomes so interesting to me, and I think this is a view of him that no one else shares. Miyazaki desperately wants to be optimistic about the world but can’t help but be misanthropic. He sees no hope in humanity. He sees nothing worth saving in humanity. He believes we destroy and corrupt the earth, that we bring ruin to one another. But, at the same time, he has a deep love of children and is somehow endlessly hopeful that they’ll be better than the rest of us, which is why so many of his protagonists are children. His environmentalism and anarchic tendencies are the most obvious elements that rise again and again in his films, but his misanthropy seems to be overlooked consistently. It’s something that I’ll be discussing more in the future, but Laputa is a very clear example, to me, about his feelings towards humanity, which are perhaps represented best by Muska and the army.

Sheeta and Pazu, still innocent, remain uncorrupted by the greed, selfishness, lust for power, and destructive nature of humanity, as he sees us. The pirates are more of a mix, working only for themselves, but also helping Sheeta and Pazu for their own gain. Beneath that though, they’re a family. Despite Miyazaki’s misanthropy, he’s a firm believer in community and people working together to overcome the difficulties of life, which is why the miners are also shown in such a positive light.

But, ultimately, Laputa is a film about hope and fighting for life. Not the lives of individual humans, but the life of the planet and all who inhabit it. In order to save the world, Sheeta decides to destroy her heritage and her true identity in order to keep it out of the hands of those who would weaponise it.

Sheeta and Pazu save one another and the world with the help of pirates and a bit of magic. They show us the best parts of humanity and how we should strive to behave. To put others and the world before our own interests. To not only respect nature, but to be awed by it. To find the ineffable beauty in life and love. To define humanity as a prosocial entity, rather than a destructive fungus crawling over the earth.

It’s a beautiful film full of action, humor, community, and love. There’s a quietness to much of the film and a soft beauty to it to juxtapose with the violence and chaos, all cut by humor and heart.

This is the beginning of Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki’s second film, but it defines what the studio will be. It’s a studio that’s shaped animation and especially Japanese animation for the last thirty years.

Ah, might be time to watch it again